View PDF - Connecticut Law Review

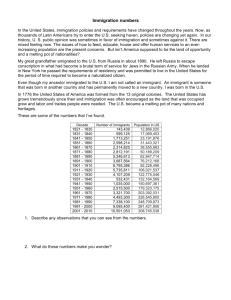

advertisement