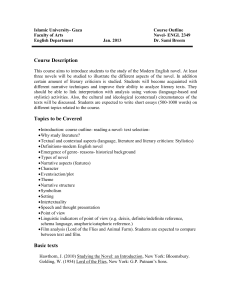

Literature Sample - Education & Schools Resources

advertisement