ARTICLE

The Effect of Simulated Ostracism on Physical Activity

Behavior in Children

AUTHORS: Jacob E. Barkley, PhD,a Sarah-Jeanne Salvy,

PhD,b and James N. Roemmich, PhDb

aDepartment of Exercise Science, The School of Health Sciences,

Kent State University, Kent, Ohio; and bDivision of Behavioral

Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, State University of New York,

University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York

KEY WORDS

ostracism, children, peer, physical activity

ABBREVIATION

SES—socioeconomic status

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: The social and emotional

burdens of ostracism are well known, but few studies have tested

whether ostracism adversely alters physical activity behaviors

that may result in maintenance of childhood obesity.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: This is the first study to experimentally

assess the effect of simulated ostracism, or social exclusion, on

physical activity behavior in children. Ostracism reduced

accelerometer counts by 22% and increased time allocated to

sedentary behaviors by 41%.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2011-0496

doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0496

Accepted for publication Oct 27, 2011

Address correspondence to Jacob E. Barkley, PhD, Kent State

University, 350 Midway Dr, 163E MACC Annex, Kent, OH 44242.

E-mail: jbarkle1@kent.edu

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2012 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have

no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

abstract

OBJECTIVES: To assess the effects of simulated ostracism on children’s

physical activity behavior, time allocated to sedentary behavior, and

liking of physical activity.

METHODS: Nineteen children (11 boys, 8 girls; age 11.7 6 1.3 years)

completed 2 experimental sessions. During each session, children

played a virtual ball-toss computer game (Cyberball). In one

session, children played Cyberball and experienced ostracism; in

the other session, they were exposed to the inclusion/control

condition. The order of conditions was randomized. After playing

Cyberball, children were taken to a gymnasium where they had

free-choice access to physical and sedentary activities for 30

minutes. Children could participate in the activities, in any pattern

they chose, for the entire period. Physical activity during the freechoice period was assessed via accelerometery and sedentary time

via observation. Finally, children reported their liking for the activity

session via a visual analog scale.

RESULTS: Children accumulated 22% fewer (P , .01) accelerometer

counts and 41% more (P , .04) minutes of sedentary activity in the

ostracized condition (8.9e+4 6 4.5e+4 counts, 11.1 6 9.3 minutes)

relative to the included condition (10.8e+4 6 4.7e+4 counts, 7.9 6

7.9 minutes). Liking (8.8 6 1.5 cm included, 8.1 6 1.9 cm ostracized)

of the activity sessions was not significantly different (P . .10) between conditions.

CONCLUSIONS: Simulated ostracism elicits decreased subsequent

physical activity participation in children. Ostracism may contribute

to children’s lack of physical activity. Pediatrics 2012;129:e659–e666

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 3, March 2012

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016

e659

Positive interaction with peers and

friends is associated with increased

participation in physical activity in children and adolescents.1–6 This has been

demonstrated by using survey research

and, to a lesser extent, in a few controlled studies where the presence or

absence of peers and/or friends was

manipulated.1–6 Conversely, negative

social interactions with peers (ie, peer

victimization or rejection and prejudice)

have been correlated with decreased

physical activity participation in children and adolescents.7–14 This is problematic, as a lack of physical activity in

children and adolescents is associated

with the development of obesity and

other health difficulties.15–18 The research on adverse social interaction

and physical activity would greatly

benefit from experimental designs that

allow for stronger causal inferences.

Furthermore, the existing research on

adverse social interaction and physical

activity has focused almost exclusively on

overt peer victimization and criticism7–14

and no study, to our knowledge, has examined the specific impact of ostracism

or social exclusion on youths’ physical

activity. In contrast to overt peer rejection and criticism that often involves

explicit declarations that an individual

or group is not wanted, ostracism is the

intentional ignoring or excluding of an

individual or group by another individual

or group.19 Ostracism threatens an

individual’s need to belong and also

produces psychological and physiologic

responses that are indicative of a stress

response.20,21 The social and emotional

burdens of ostracism are well known,22,

23 but no studies have tested whether

ostracism adversely alters physical activity behaviors.

This study assessed the effects of simulated ostracism on children’s physical

activity behavior and liking of that

physical activity. The Cyberball game

was used to induce ostracism or inclusion. Cyberball is a well-validated

e660

computerized ball-tossing game used

to induce a brief episode of simulated

ostracism or include the individual in

game play.24–27 When playing Cyberball

and experiencing ostracism, individuals exhibit both perceptual and physiologic changes that can be observed in

a research setting. Individuals who

play Cyberball and experience ostracism report greater feelings of sadness, aloneness, and exclusion versus

those being included during Cyberball

play.23 In addition, functional MRI of

brain activity has shown that experiencing the “social pain” of ostracism

during Cyberball game play is very

similar to experiencing physical pain.20

,21 Liking (ie, hedonics) was assessed

via a validated visual analog scale and

is an effective rating of a behavior that

is controlled by the opioid neurotransmitter system.28 Liking of physical

activity is associated with actual physical activity behavior in children.29–32 We

hypothesized that simulated ostracism

would decrease children’s amount of

physical activity and their liking of the

activity and increase the time allocated

to sedentary behavior relative to an

included condition.

METHODS

Participants

A total of 19 children (11 boys, 8 girls)

between the ages of 8 and 12 years with

no contraindications to physical activity

participated in the current study. Participants were recruited through flyers

posted in the local community and from

a database of individuals who had previously contacted the Applied Physiology

Laboratory at Kent State University to

participate in separate, unrelated

studies. Children were excluded if

they exhibited any contraindications

(eg, orthopedic injury) to physical

activity. Before participation, children

and their parent/guardian read and

signed informed assent and consent

forms, respectively. This study was

BARKLEY et al

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016

approved by the Kent State University

Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

Children meeting the entry criteria

were invited to the Applied Physiology

Laboratory at Kent State University for 2

separate visits. During the first visit,

children’s height and weight were

assessed, and children then sampled

the physical and sedentary activities in

a gymnasium that was located within

the same building and on the same

floor as the Applied Physiology Laboratory (described later in this article).

The walk to the gymnasium from the

laboratory took ∼1 minute.

After sampling the activities, children

played the virtual ball-toss computer

game, Cyberball, in the laboratory.

Cyberball is a ball-throwing simulation

that appears as a simulated Internet

browser on a computer. The game has

been used in adults and youth.33,34

During Cyberball, the participant controls the character at the bottom of the

screen, and there are 2 additional

characters that are programmed by

the computer to either include or exclude the participant from the balltossing game. Participants are told

they are playing the Cyberball game

over the Internet with 2 other children

who are “like them.” Participants are

told they can throw the ball to either

player on the screen. By mouse-clicking

on the appropriate player’s icon, the

participant then passes the ball to that

player. In the ostracized condition, the

participant receives the ball twice, and

thereafter, never receives it again. In

the included condition, the participant

receives the ball 33% of the time. In

both conditions, there are a total of 30

throws and the manipulation lasts 3

minutes. Cyberball has been shown to

be a valid simulation of ostracism, as

individuals who play the game in the

ostracized condition have reliably

reported greater negative feelings

ARTICLE

(ie, feeling “bad”), having less control

of their emotions, and having less of a

sense of belonging to a group.23

During 1 session, participants were

assigned to the ostracism condition and

were accordingly socially excluded.

During the other session, participants

were exposed to the inclusion/control

condition. The order of presentation

of the conditions was randomly determined across participants. After completing the Cyberball game on both

visits, participants completed a manipulation check to assess the effects

of Cyberball on psychological needs,

moods, and perception of inclusion/

exclusion (described later in this article).

After completing the manipulation

check, participants were given free

access to the previously sampled activities for 30 minutes. Children were

free to use any of the physical and/or

sedentary activity equipment they

wished, in any pattern, for the entire

session. Children’s behavior was monitored by a member of the research

team who was present in the gymnasium discreetly observing the participant. To minimize the impact of social

influence on the children’s behavior,

there were no additional individuals in

the gymnasium during each 30-minute

activity session other than the research

team member observing the child. At the

conclusion of the 30-minute session,

participants were asked to report their

liking of that session. All activity sessions

took place between Monday and Friday,

after school time in the late afternoon (3

PM) to early evening (6 PM). At the end of

the second visit, all participants were

debriefed as to the true nature of the

experiment, and they were compensated for their participation with a

$20.00 gift card to a local store.

Children were given free access to

physical and sedentary activities

in a 4360-sq ft gymnasium during each

30-minute activity session. Physical

activities/equipment included the

following: five 1-ft (0.305 m)-tall modified hurdles, jump rope, several Nerf

footballs and flying discs with targets

and goals (Hasbro, Pawtucket, RI),

standing long jump, kicking a soccer

ball around a series of 7 cones, shooting

a basketball at a standard 10-ft (3.05 m)

hoop, and navigating an obstacle

course made up of gymnastic/soft-play

equipment (UCS Inc, Lincolnton, NC).

The obstacle course consisted of the

following: foam gymnastic/soft-play

equipment arranged in order, one 60in (1.52 m)-long by 48-in (1.22 m)-wide

ramp ascending at 15° to a peak

height of 15 in (0.38 m) butting up to

a 34-in (0.86 m)-long by 24-in (0.69 m)diameter octagonal cylinder laid horizontally. Immediately after the cylinder

there was a 60-in (1.52 m)-long by 36-in

(0.91 m)-wide ramp ascending at 15° to

a peak height of 15 in (0.38 m) butting

up to a 48-in (1.22 m)-tall octagonal

ring with a 28-in (0.71 m) diameter

opening and another 60-in (1.52 m)long by 36-in (0.91 m)-wide ramp

placed in a descending fashion, after

the octagonal ring. Sedentary activities/

equipment were located on a table, with

a chair, within the gymnasium and included drawing, crossword puzzles,

word finds, reading magazines, and

the matching game Perfection (Milton

Bradley Company, East Longmeadow, MA).

(ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL) on their hips,

snug against the body. Epoch length was

set to 60 seconds and per-minute accelerometer counts were summed for the

measure of physical activity behavior per

activity session. The ActiGraph is a valid

and reliable tool for quantifying physical

activity in children and adolescents.36

Sedentary Activity Observation

During each 30-minute activity session,

the amount of time children allocated to

participating in sedentary activities was

monitored via a stopwatch (Traceable

Stopwatch, Fisher Scientific, Waltham,

MA) and recorded on a data-entry form

by the investigator discretely observing

the session. Children were informed that

the observer was present to ensure their

safety while playing alone in the gymnasium. To minimize the observer’s influence on children’s behavior, once an

activity session began, the investigator

observing the session did not speak

with the child unless the child asked a

question related to the activity session

or the child’s behavior was placing the

child at risk (ie, misuse of equipment in

the gymnasium). Sedentary time was

recorded from the moment the child

came to the sedentary table and sat in

the chair. Children were informed that if

they wished to participate in the “table”

(ie, sedentary) activities, they were to do

so while seated.

Measurements

Anthropometrics

Liking

Body weight was assessed to the

nearest 0.2 kg by using a balance-beam

scale (Health O Meter, Alsip, IL). Height

was assessed to the nearest 1.0 mm

using a calibrated stadiometer (Health

O Meter). The Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention’s BMI Percentile

Calculator for Child and Teen was used

to calculate BMI percentile.35

Liking of the physical activities from each

30-minute activity session was assessed

using a visual analog scale consisting of

a 10-cm line anchored by “do not like it at

all” on the left side and “like it very much”

on the right side. Liking, or hedonics, is

an effective rating of a behavior that

directly correlates with physical activity participation.29–32

Accelerometry

Manipulation Check

During each 30-minute activity session,

children woreanActiGraphGT1MMonitor

Immediately on completion of Cyberball

game play, during both conditions

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 3, March 2012

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016

e661

(ostracized, included), children read and

completed the Aversive ImpactIndex.The

Aversive Impact Index is a validated

questionnaire designed to assess positive and negative affective states after

Cyberball play.23 Each statement (eg, “I

felt rejected”) requires participants to

respond across a 5-point scale anchored by 1 “Not at all” to 5 “Extremely.”

The scores from each positive statement (eg, “I felt good about myself”)

and each negative statement (eg, “I

felt rejected”) were separately summed to provide indices of positive and

negative affective states after each

time children played Cyberball. The

Aversive Impact Index also assesses

participants’ perceptions of how frequently they were thrown the ball

and how excluded they were during

Cyberball play. If a child required assistance when completing the Aversive

Impact Index (eg, clarification of any of

the items on the questionnaire), it was

provided by a member of the research

team.

Statistical Analysis

Individual Characteristics

Differences in boys’ and girls’ physical

characteristics (height, weight, BMI

percentile, and age) were analyzed

with independent-sample t tests.

Manipulation Check

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used

to assess differences across the included and ostracized conditions in the

scores from the negative and positive

items on the Aversive Impact Index, how

frequently children perceived they received the ball, and how excluded they

felt. Spearmancorrelationanalyseswere

used to assess relationships between

changes in the positive and negative

items on the Aversive Impact Index and

changes in measures of physical activity behavior and liking of each activity

session from the included to the

ostracized conditions.

e662

Effects of Ostracism

Two gender (male, female) by 2 conditions

(included, ostracized) analyses of variance with repeated measures were used

to assess differences in accelerometer

counts,timeallocatedtosedentaryactivity,

and liking across the conditions. There

were no significant main (F[1, 17] ,0.90,

P . .3) or interaction (F[1, 17] ,0.96, P .

.3) effects of gender, so results from these

analyses are described with both genders

pooled into a single group.

All statistical analyses were conducted

using SPSS for Windows (version 17.0,

SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Individual Characteristics

Participant physical characteristics are

shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences for age, height,

weight, or BMI percentile (t[18] #1.70,

P $ .12) between boys and girls.

Manipulation Check

Children had greater scores for the

negative items (z = 3.4, P = .001) and

lower scores for the positive items (z =

3.1, P = .002) on the Aversive Impact

Index in the ostracized condition than

in the included condition (Table 2).

Children indicated greater feelings of

being excluded (z = 3.6, P , .001) and

ignored (z = 3.7, P , .001) during the

ostracized condition relative to the included condition (Table 2). Children

also indicated that they received a

greater (z = 3.8, P , .001) percentage

of the total throws in the included

condition (M = 33.1, SD = 8.6) than the

TABLE 1 Participant Physical

Characteristics

Variable

Boys

(n = 11)

Girls

(n = 8)

Age, y

Height, cm

Weight, kg

BMI percentile

11.3 6 1.7

148.5 6 12.3

53.7 6 25.7

74.0 6 27.0

11.5 6 1.9

151.2 6 10.7

42.1 6 9.4

52.4 6 29.7

Data are presented as the means 6 SD.

BARKLEY et al

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016

ostracized condition (M = 9.6, SD = 7.2).

Although the manipulation elicited

changes in mood measures, mood

measures were not (P . .18) correlated

with the behavioral measures or liking

of the activity sessions. For example,

changes in accelerometer counts from

the included to ostracized conditions

were not correlated with changes in the

total positive (r = 20.33, P . .18) or

negative (r = 0.13, P . .6) scores from

items on the Aversive Impact Index.

Effects of Ostracism

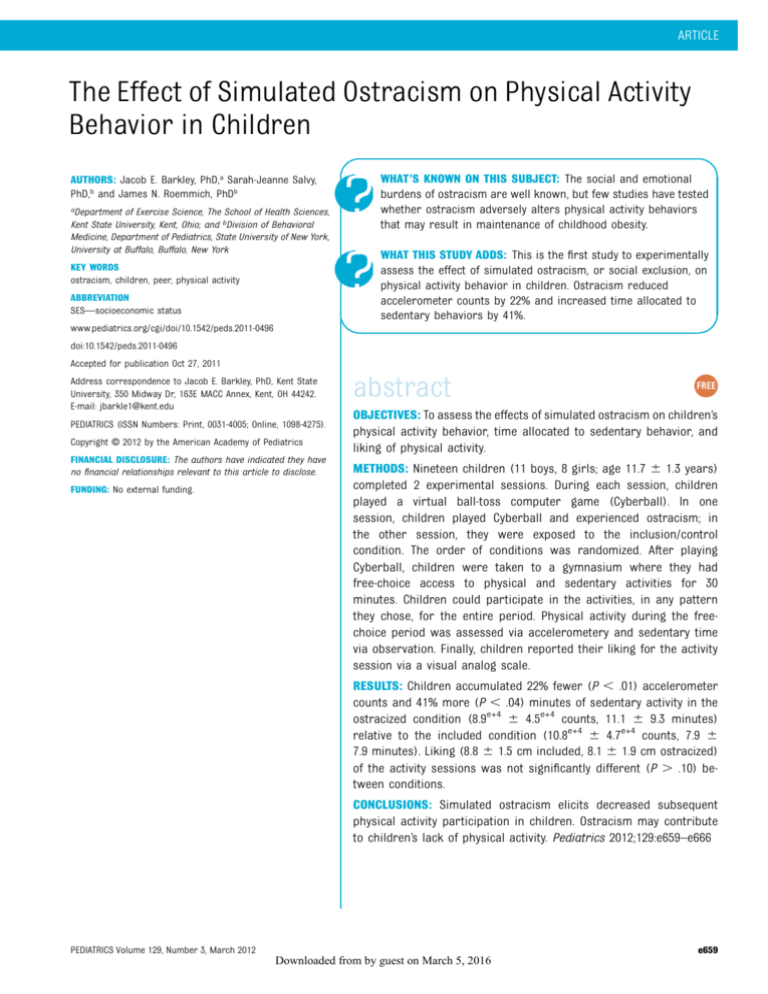

Children accumulated more accelerometer counts (F[1, 17] = 10.10, P , .01)

in the included condition than in the

ostracized condition (Fig 1). Children

allocated more time to sedentary activity (F[1, 17] = 4.95, P = .04) in the

ostracized condition than the included

condition (Fig 1). There were no significant differences (F[1, 17] ,1.0, P . .10)

in liking (M = 8.8, SD = 1.5 cm included,

M = 8.1, SD = 1.9 cm ostracized) between the ostracism and the inclusion

conditions.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to assess the acute

impact of a bout of simulated ostracism

on children’s choice to be physically

active or sedentary. Findings indicated

that children accumulated 22% fewer

accelerometer counts and allocated

41% more time to sedentary activities

in the ostracism condition than the

inclusion/control condition. The current results suggest that ostracism

may directly reduce physical activity

and increase sedentary behaviors.

These findings are worrisome, because

the lack of physical activity and engagement in sedentary behaviors in

children and adolescents are concurrently and prospectively related to

obesity and other health difficulties.15–18

Although the ways in which difficulties

with peers and friends affect youths’

cognitive and psychosocial development

ARTICLE

TABLE 2 Aversive Impact Index and Manipulation Check Scores

Variable

Included

(n = 19)

Ostracized

(n = 19)

AII: Negative items*

AII: Positive items*

MC: Feelings of being excluded*

MC: Feelings of being ignored*

17.2 6 7.0

31.2 6 6.7

1.5 6 0.9

1.3 6 0.7

30.2 6 9.8

22.4 6 7.5

3.8 6 1.4

4.0 6 1.3

Data are presented as the means 6 SD. AII, Aversive Impact Index scores; MC, manipulation check scores.

* Significant difference between the included and ostracized conditions (P , .002).

FIGURE 1

Total accelerometer counts (upper panel) and minutes of sedentary activity (bottom panel). *Significant differences between the included and ostracized conditions (P , .04).

have been well studied,22,23,37 few

studies have examined the impact of

social adversity on youths’ physical

activity and sedentary behavior.7–14

These previous studies have indicated

that children who report a greater

amount of social adversity report less

physical activity behavior than their

socially accepted peers. The existing

literature on social adversity and

physical activity behavior in children,

however, is limited to self-report data

and lacks the use of carefully controlled experimental designs. The current work extends previous research

by using an experimental design and

conducting the experiment in a controlled environment, which provided

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 3, March 2012

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016

the ability to manipulate ostracism and

inclusion and determine the extent to

which ostracism caused a reduction in

subsequent physical activity and sedentary behaviors in children.

Interestingly, the current findings indicate that physical activity behavior

was decreased after an episode of ostracism, whereas liking of the activity

sessions was not affected. Although it is

unclear why such a paradoxical effect

occurred, previous research may offer

some insight. Previous research has

indicated that mood or emotional distress is not the process mediating

behavioral changes in response to

ostracism.38–40 Our own findings of a

lack of a relationship between changes

in the Aversive Impact Index and physical activity behavior support this. Instead, Williams19 has suggested that

ostracism is similar to experiencing

“physical pain.” This “pain” causes the

brain to focus on the source of the

ostracism and apply the appropriate

coping mechanism (ie, “freezing”; becoming still or motionless) and this

could promote greater sedentary behavior.40 The preoccupation in finding

a coping mechanism after ostracism

negatively affects performance on

tasks that involve active thought or

those that require executive function.41

If ostracism impairs executive function,

it likely affects the decision to respond

actively.41–43 Ostracism may temporarily paralyze or induce a state of apathy

or inhibit behavioral activation in participants, promoting sedentary choices;

however, because the effects of ostracism are temporary, by the end of the

30-minute activity session (when liking

was assessed) children may have recovered and begun to like the physical

activity as much as the included condition. Future studies would benefit

from assessing activity liking at multiple times to determine if it improves as

the effects of ostracism likely abate, and

also whether engagement in physical

e663

activity helps in recovering following

social exclusion.

Although the current study is the first to

examine the effect of ostracism on

physical activity behavior, previous

studies have examined the effects of

simulated ostracism on eating. Each of

these previous studies demonstrated

that a bout of ostracism increases

eating behavior.33,34,44,45 These studies

also identified possible factors that

moderate the effects of ostracism on

eating behavior. Adults who were considered socially anxious33 and those

prone to overeating44 ate more after

experiencing ostracism than adults

who were not socially anxious or prone

to overeating. Ostracism also increases

overweight youths’ motivation to eat and

food intake, whereas nonoverweight

youth do not alter their eating behavior

or motivation after experiencing ostracism.34 It is possible that additional factors, that were not presently assessed,

also act to moderate the effects of ostracism on physical activity behavior.

Given the previous evidence supporting

the importance of children’s weight

status,46 the relative reinforcing value of

physical activity versus sedentary alternatives,47 and self-efficacy for physical

activity48,49 in predicting physical activity

behavior in children, it would be logical

to assess such variables as potential

mediators or moderators of the effects

of ostracism on physical activity and

sedentary behavior in future studies.

Although the present results are intriguing, there are limitations to this

study. Primarily, the sample size (n =

19) was small and children were not

recruited based on adiposity. Recruiting a larger sample size of both normal

weight and overweight/obese youth

would allow for the assessment of the

moderators proposed previously (ie,

overweight status, relative reinforcing

value, and self-efficacy for physical

activity), as well as additional potential

moderators that were not presently

assessed, such as self-reported physical activity and eating behaviors. Although the sample size from the

current study was small, the accelerometer counts data from the included

and ostracized conditions were normally distributed and the difference

between these conditions was easily

large enough (22%) to yield statistical

significance. Future studies should

measure liking or other possible mediators more frequently during the

activity sessions, as these variables

may fluctuate the longer a participant

is physically active after being ostracized. This was also a fairly homogeneous sample in that all, except 2

(Hispanic), of the children were white.

Future research should examine

a more ethnically diverse group of

participants. Furthermore, although all

the families in the current study largely

came from middle-class suburban

neighborhoods and small cities, there

was no specific assessment of parental

socioeconomic status (SES). Assessment of parental SES will be important

for understanding whether it moderates the effect of ostracism on activity

choice and to inform to which SES

levels these results may be generalized. We also acknowledge that volunteer bias is a potential limitation and

this may help explain the homogeneity

of the sample.

physical activity, this is the first study

to experimentally examine the effects

of a brief episode of simulated ostracism on subsequent physical and

sedentary activity behavior in children. Children exhibited a decrease

in physical activity counts and an increase in time allocated to sedentary

behavior after being ostracized relative to the included condition. This

suggests that experiencing ostracism

has an immediate negative impact

on children’s choice to be physically

active. These findings are consistent with previous results from

nonexperimental survey research,

indicating that social adversity is

associated with lower levels of physical activity participation in children. Additional research examining

potential differences in these effects between normal weight and

overweight/obese children is warranted, because overweight youth

are at greater risk of difficulties with

the larger peer group. The present

results provide the first causal evidence that ostracism may reinforce

behaviors that lead to obesity in

children. The consideration of the

effect of adverse social interaction

on physical activity behavior may further our understanding of physical and

behavioral health trajectories.

Although previous, nonexperimental

studies have shown a link between selfreported social adversity and a lack of

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr Jason D. Ridgel, Fellow of the

American Academy of Family Practice,

contributed to the review of this manuscript. As a family physician, Dr Ridgel

ensured that the terminology used

herein was appropriate for family physicians and pediatricians. The authors

sincerely thank Dr Ridgel for his expert assistance.

physical activity performed in 8- to 12-yearold boys. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2011;23(1):49–60

2. Salvy SJ, Bowker JW, Roemmich JN, et al.

Peer influence on children’s physical

CONCLUSIONS

REFERENCES

1. Rittenhouse MA, Salvy SJ, Barkley JE. The

effect of peer influence on the amount of

e664

BARKLEY et al

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016

ARTICLE

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

activity: an experience sampling study.

J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(1):39–49

Salvy SJ, Roemmich JN, Bowker JC,

Romero ND, Stadler PJ, Epstein LH. Effect

of peers and friends on youth physical

activity and motivation to be physically

active. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(2):217–

225

Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Strycker LA. Sources and types of social support in youth

physical activity. Health Psychol. 2005;24(1):

3–10

Finnerty T, Reeves S, Dabinett J, Jeanes YM,

Vögele C. Effects of peer influence on dietary

intake and physical activity in schoolchildren. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(3):

376–383

Springer AE, Kelder SH, Hoelscher DM.

Social support, physical activity and sedentary behavior among 6th-grade girls:

a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys

Act. 2006;3(1):8

Faith MS, Leone MA, Ayers TS, Heo M, Pietrobelli A. Weight criticism during physical

activity, coping skills, and reported physical activity in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110

(2 pt 1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/

cgi/content/full/110/2pt1/e23

Gosling R, Stanistreet D, Swami V. ‘If Michael Owen drinks it, why can’t I?’ — 9 and

10 year olds’ perceptions of physical activity and healthy eating. Health Educ J.

2008;67(3):167–181

Hohepa M, Scragg R, Schofield G, Kolt GS,

Schaaf D. Social support for youth physical

activity: importance of siblings, parents,

friends and school support across a segmented school day. Int J Behav Nutr Phys

Act. 2007;4:54

Kunesh MA, Hasbrook CA, Lewthwaite R.

Physical activity socialization: peer interactions and affective responses among a

sample of sixth grade girls. Sociol Sport J.

1992;9:385–396

Page RM, Frey J, Talbert R, Falk C. Children’s

feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction: Relationship to measures of physical fitness and activity. J Teach Phys Educ.

1992;11:211–219

Smith AL. Perceptions of peer relationships

and physical activity participation in early

adolescence. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1999;

21:329–350

Storch EA, Milsom VA, Debraganza N, Lewin

AB, Geffken GR, Silverstein JH. Peer victimization, psychosocial adjustment, and physical activity in overweight and at-risk-foroverweight youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;

32(1):80–89

Slater A, Tiggemann M. Gender differences

in adolescent sport participation, teasing,

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

self-objectification and body image concerns. J Adolesc. 2011;34(3):455–463 [Corrected Proof.]

Anderssen SA, Holme I, Urdal P, Hjermann I.

Associations between central obesity and

indexes of hemostatic, carbohydrate and

lipid metabolism. Results of a 1-year intervention from the Oslo Diet and Exercise

Study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1998;8(2):

109–115

Dietz WH, Jr, Gortmaker SL. Do we fatten

our children at the television set? Obesity

and television viewing in children and

adolescents. Pediatrics. 1985;75(5):807–812

Dietz WH, Gortmaker SL. Preventing obesity

in children and adolescents. Annu Rev

Public Health. 2001;22:337–353

Dietz WH, Robinson TN. Clinical practice.

Overweight children and adolescents.

N Engl J Med. 2005;352(20):2100–2109

Williams KD. Ostracism: the kiss of social

death. Social and Personality Psychology

Compass. 2007;1(1):236–247

Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Why rejection hurts: a common neural alarm

system for physical and social pain. Trends

Cogn Sci. 2004;8(7):294–300

Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD.

Does rejection hurt? An FMRI study of social exclusion. Science. 2003;302(5643):

290–292

Smart Richman L, Leary MR. Reactions to

discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism,

and other forms of interpersonal rejection:

a multimotive model. Psychol Rev. 2009;116

(2):365–383

Williams KD, Cheung CK, Choi W. Cyberostracism: effects of being ignored over the

Internet. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(5):

748–762

van Beest I, Williams KD. When inclusion

costs and ostracism pays, ostracism still

hurts. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(5):918–

928

Sebastian C, Blakemore SJ, Charman T.

Reactions to ostracism in adolescents with

autism spectrum conditions. J Autism Dev

Disord. 2009;39(8):1122–1130

Williams KD, Jarvis B. Cyberball: a program

for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behav Res Methods. 2006;38(1):174–180

Harmon-Jones E, Peterson CK, Harris CR.

Jealousy: novel methods and neural correlates. Emotion. 2009;9(1):113–117

Berridge KC. Food reward: brain substrates

of wanting and liking. Neurosci Biobehav

Rev. 1996;20(1):1–25

Craig S, Goldberg J, Dietz WH. Psychosocial

correlates of physical activity among fifth

PEDIATRICS Volume 129, Number 3, March 2012

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

and eighth graders. Prev Med. 1996;25(5):

506–513

Motl RW, Dishman RK, Saunders R, Dowda

M, Felton G, Pate RR. Measuring enjoyment

of physical activity in adolescent girls. Am J

Prev Med. 2001;21(2):110–117

DiLorenzo TM, Stucky-Ropp RC, Vander Wal

JS, Gotham HJ. Determinants of exercise

among children. II. A longitudinal analysis.

Prev Med. 1998;27(3):470–477

Roemmich JN, Barkley JE, Lobarinas CL,

Foster JH, White TM, Epstein LH. Association

of liking and reinforcing value with children’s physical activity. Physiol Behav. 2008;

93(4-5):1011–1018

Oaten M, Williams KD, Jones A, Zadro L. The

effects of ostracism on self-regulation in

the socially anxious. J Soc Clin Psychol.

2008;27(5):471–504

Salvy SJ, Bowker JC, Nitecki LA, Kluczynski

MA, Germeroth LJ, Roemmich JN. Impact

of simulated ostracism on overweight and

normal-weight youths’ motivation to eat

and food intake. Appetite. 2011;56(1):39–

45

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. BMI percentile calculator for child

and teen. Available at: http://apps.nccd.

cdc.gov/dnpabmi/. Accessed September 1,

2010

Freedson P, Pober D, Janz KF. Calibration of

accelerometer output for children. Med

Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(suppl 11):S523–

S530

Forgas JP, Williams KD, Wheeler L. The Social Mind: Cognitive and Motivational

Aspects of Interpersonal Behavior. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press;

2001

Twenge JM, Baumeister RF, Tice DM, Stucke

TS. If you can’t join them, beat them: effects

of social exclusion on aggressive behavior.

J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(6):1058–1069

Twenge JM, Catanese KR, Baumeister RF.

Social exclusion causes self-defeating behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83(3):606–

615

Twenge JM, Catanese KR, Baumeister RF.

Social exclusion and the deconstructed

state: time perception, meaninglessness,

lethargy, lack of emotion, and self-awareness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(3):409–423

Baumeister RF, Twenge JM, Nuss CK. Effects

of social exclusion on cognitive processes:

anticipated aloneness reduces intelligent

thought. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83(4):

817–827

Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M,

Tice DM. Ego depletion: is the active self a

limited resource? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;

74(5):1252–1265

e665

43. Muraven M, Tice DM, Baumeister RF. Selfcontrol as limited resource: regulatory

depletion patterns. J Pers Soc Psychol.

1998;74(3):774–789

44. Oliver KG, Huon GF, Zadro L, Williams KD.

The role of interpersonal stress in overeating among high and low disinhibitors.

Eat Behav. 2001;2(1):19–26

45. Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ,

Twenge JM. Social exclusion impairs

e666

self-regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;

88(4):589–604

46. Steinbeck KS. The importance of physical

activity in the prevention of overweight and

obesity in childhood: a review and an

opinion. Obes Rev. 2001;2(2):117–130

47. Epstein LH, Smith JA, Vara LS, Rodefer JS.

Behavioral economic analysis of activity

choice in obese children. Health Psychol.

1991;10(5):311–316

BARKLEY et al

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016

48. Ball GD, Marshall JD, McCargar LJ.

Physical activity, aerobic fitness, selfperception, and dietary intake in at risk

of overweight and normal weight children. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2005;66(3):

162–169

49. Strauss RS, Rodzilsky D, Burack G, Colin M.

Psychosocial correlates of physical activity

in healthy children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc

Med. 2001;155(8):897–902

The Effect of Simulated Ostracism on Physical Activity Behavior in Children

Jacob E. Barkley, Sarah-Jeanne Salvy and James N. Roemmich

Pediatrics 2012;129;e659; originally published online February 6, 2012;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-0496

Updated Information &

Services

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

/content/129/3/e659.full.html

References

This article cites 47 articles, 6 of which can be accessed free

at:

/content/129/3/e659.full.html#ref-list-1

Subspecialty Collections

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in

the following collection(s):

Sports Medicine/Physical Fitness

/cgi/collection/sports_medicine:physical_fitness_sub

Permissions & Licensing

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2012 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016

The Effect of Simulated Ostracism on Physical Activity Behavior in Children

Jacob E. Barkley, Sarah-Jeanne Salvy and James N. Roemmich

Pediatrics 2012;129;e659; originally published online February 6, 2012;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-0496

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

/content/129/3/e659.full.html

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2012 by the American Academy

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from by guest on March 5, 2016