ARTICLE IN PRESS

Journal of

Experimental

Social Psychology

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology xxx (2004) xxx–xxx

www.elsevier.com/locate/jesp

How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to

lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem,

and meaningful existenceq

Lisa Zadro,a,* Kipling D. Williams,b,* and Rick Richardsona

a

School of Psychology, Faculty of Science, University of New South Wales, UNSW Sydney 2052, Australia

b

Department of Psychology, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia

Received 20 June 2003; revised 22 October 2003

Abstract

Previous research has demonstrated self-reports of lower levels of four fundamental needs as a result of short periods of face-toface ostracism, as well as short periods of Internet ostracism (Cyberball), even when the ostracizing others are unseen, unknown, and

not-to-be met. In an attempt to reduce the ostracism experience to a level that would no longer be aversive, we (in Study 1) convinced participants that they were playing Cyberball against a computer, yet still found comparable negative impact compared to

when the participants thought they were being ostracized by real others. In Study 2, we took this a step further, and additionally

manipulated whether the participants were told the computer or humans were scripted (or told) what to do in the game. Once again,

even after removing all remnants of sinister attributions, ostracism was similarly aversive. We interpret these results as strong

evidence for a very primitive and automatic adaptive sensitivity to even the slightest hint of social exclusion.

Ó 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Ostracism—the act of being excluded and ignored

(Williams, 2001)—is ubiquitous. Reviewing the ethological, anthropological, and social psychological literature reveals that ostracism is used by many species, by

children and adults, in primitive tribes and modern industrialized societies, as a formal method of reprimand

among nations, institutions, and organizations and as

an informal emergent reaction on playgrounds and

hallways, with large groups, small groups, and dyads.

Ostracism is also powerful. Studies have shown that

people subjected to ostracism for a short period of time

report worsened mood, anger, and lower levels of four

state measures of needs proposed by Williams (1997,

2001) to be threatened by ostracism: belonging, control,

q

This research was funded by an Australian Research Council

Grant to the second author, and comprised part of the first authorÕs

doctoral dissertation. We would like to extend our thanks to Bibb

Latane for comments that initially triggered our interest in pursuing

this line of inquiry, and Keith Lim and Trevor Case for their technical

assistance.

*

Corresponding authors.

E-mail addresses: l.zadro@unsw.edu.au (L. Zadro), kip@psy.mq.

edu.au (K.D. Williams).

0022-1031/$ - see front matter Ó 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2003.11.006

self-esteem, and meaningful existence. These studies

consisted largely of a laboratory-based ball-tossing

paradigm, in which participants partook in a spontaneous ball-toss game with two other confederate participants. When the other two individuals began tossing

the ball just between themselves, ostracized participants

slumped in their chairs, looking despondent, after only

4 min. Studies of long-term ostracism report incidences

of attempted suicide and depression (Williams & Zadro,

2001), and even mass-shootings (Leary, Kowalski,

Smith, & Phillips, 2003).

Recently, Williams, Cheung, and Choi (2000) reported that individuals who played a virtual ball-toss

game on the computer, ostensibly with others who were

logged on to the website, also reported worsened mood

and lower need levels. Additionally, if given the opportunity to make spatial judgments with a new group

of individuals, ostracized participants were more likely

to conform to this groupÕs unanimously incorrect answers.

One goal of the Williams et al. (2000) research was to

first establish a baseline condition in which ostracism

would have no effects, and then to add on necessary

ARTICLE IN PRESS

2

L. Zadro et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology xxx (2004) xxx–xxx

factors until ostracism had a negative impact on the four

needs. The authors were surprised to find out that what

they thought would be the baseline turned out to be

sufficiently adverse. One goal of the present studies,

therefore, was to create conditions even less meaningful

than those in the Williams et al. (2000) studies, in order

to determine the necessary and sufficient conditions for

ostracism to have an aversive impact. To the extent that

such a baseline can be established, then we can gain a

clearer idea what aspects of ostracism are essential.

Study 1

In Study 1, participants were either ignored or included during Cyberball—a cyber analogue of a balltossing game (Williams et al., 2000, 2002)—by two

other players whose identity was manipulated. Targets

were told that they were playing Cyberball with either

two computer-generated players or two human players

prior to the start of the game. If the identity of the

source is an important component in determining the

aversiveness of ostracism, then targets who are ostracized by two human players should report lower levels

of primary needs than targets who are ostracized by

two computer-generated players or targets who are

included in the game. If the identity of the source is not

important—rather, the very act of ostracism is aversive

enough to induce deleterious psychological effects—

then targets who are ostracized by humans or computers should both report lower levels of mood and of

the four primary needs when compared to targets who

are included in the game.

Method

Participants and design

Eighty first-year undergraduates enrolled in introductory psychology at the University of New South

Wales were randomly assigned to a 2 (inclusionary status: ostracism vs. inclusion) 2 (attributed source:

computer-generated players or human players) betweenS design. Participants volunteered to take part in the

experiment in return for course credit. Eighteen participants were excluded because of technical difficulties

with the computers and the Internet connection, thus

the final experiment consisted of 62 participants (20

males, 42 female, M age ¼ 19.9, SD ¼ 2:7).

Procedure

One participant per session arrived at the laboratory,

and was seated in front of a computer.1 Participants

were told that the study involved the effects of mental

1

In both studies, cardiovascular measures were taken periodically,

but only the self-report data are reported in the present paper.

visualization, and that to assist them in practicing their

skills at mental visualization they would be playing an

Internet ball-toss game on the computer. They were told

that performance in the game was unimportant, and

instead, the game was merely a means for them to engage their mental visualization skills. They were asked to

visualize the situation, themselves, and the other players.

The game was accessed via the Internet (a downloadable

version of this game is available at: http://www.psy.mq.edu.au/staff/kip/Announce/cyberball). The game depicts three ball-tossers, the middle one representing the

participant. The game is animated and shows the icon

throwing a ball to one of the other two. When the ball

was tossed to the participants, they were instructed to

click on one of the other two icons to indicate their intended recipient, and the ball would move toward that

icon. The game was set for 40 total throws (the game

lasted approximately 6 min). Once the instructions were

read, the participant clicked the ‘‘Next’’ link and the

program randomly assigned them to one of the four

conditions. At the end of the game, the website instructed participants to inform the experimenter that

they had finished, and they were then instructed to fill

out a post-experiment questionnaire.

Inclusion/ostracism manipulation. If assigned to the

inclusion condition, participants received the ball for

roughly one-third of the total throws. If assigned to the

ostracism condition, participants received the ball twice

at the beginning of the game, and for the remaining

time, never received the ball again.

Sources manipulation. Half the participants were told

that they were playing with two other individuals who

were stationed in similar laboratories at two other universities in Sydney. This cover story was augmented by

staged phone calls to the other experimenters making

sure that their participants were ready to go. The other

half were told that they were playing the game with a

computer.

Dependent measures. The questionnaire contained

several manipulation checks for inclusion/ostracism:

‘‘What percent of the throws were thrown to you?,’’ ‘‘To

what extent were you included by the other participants

during the game?,’’ and a 9-point bipolar scale (‘‘accepted/rejected’’). The questionnaire also contained a

number of questions that asked participants to assess

their levels of four needs that they felt during the game.

These needs were: belonging (‘‘I felt poorly accepted by

the other participants,’’ ‘‘I felt as though I had made a

‘‘connection’’ or bonded with one or more of the participants during the Cyberball game,’’ ‘‘I felt like an

outsider during the Cyberball game’’), control (‘‘I felt

that I was able to throw the ball as often as I wanted

during the game,’’ ‘‘I felt somewhat frustrated during

the Cyberball game,’’ ‘‘I felt in control during the Cyberball game’’), self-esteem (‘‘During the Cyberball

game, I felt good about myself,’’ ‘‘I felt that the other

ARTICLE IN PRESS

L. Zadro et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology xxx (2004) xxx–xxx

3

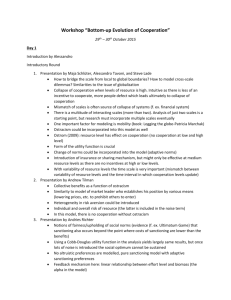

Table 1

Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) of variables in Study 1 (all scales 1 ¼ not at all to 9 ¼ very much so, unless otherwise stated)

Source

Human

Fundamental needsa

Belonging (a ¼ :74)

F ð1; 57Þ ¼ 34:99, p < :0005b

Control (a ¼ :72)

F ð1; 57Þ ¼ 32:5, p < :0005

Self-esteem (a ¼ :70)

F ð1; 57Þ ¼ 11:1, p ¼ :002

Meaningful existence (a ¼ :66)

F ð1; 58Þ ¼ 50:7, p < :0005

Moodc

Ancillary variables

I enjoyed playing the Cyberball game

F ð1; 58Þ ¼ 10:2, p ¼ :002

I felt angry during the Cyberball game

F ð1; 58Þ ¼ 8:2, p ¼ :006

Manipulation checks

To what extent were you included by the participants during the game?

F ð1; 58Þ ¼ 67:3, p < :0005

What percentage of throws do you think your received during the

Cyberball game?

F ð1; 58Þ ¼ 83:9, p < :0005

Rejected–acceptedd

F ð1; 57Þ ¼ 24:3, p < :0005

Computer

Inclusion

ðn ¼ 18Þ

Ostracism

ðn ¼ 15Þ

Inclusion

ðn ¼ 17Þ

Ostracism

ðn ¼ 12Þ

6.4 (1.5)

3.4 (2.1)

6.5 (1.7)

3.7 (2.3)

6.4 (1.7)

3.2 (1.6)

5.8 (1.7)

3.8 (1.9)

7.1 (1.2)

5.6 (2.1)

6.9 (1.1)

5.5 (2.1)

6.8 (1.4)

3.8 (1.8)

6.5 (1.5)

3.7 (1.7)

6.5 (1.2)

6.4 (1.4)

6.5 (1.1)

6.5 (1.2)

4.9 (2.4)

2.8 (2.0)

4.5 (2.2)

2.9 (2.5)

1.8 (1.6)

2.1 (1.5)

1.2 (.39)

3.3 (2.5)

7.1 (1.6)

2.7 (2.0)

6.1 (1.8)

2.8 (2.1)

37.1 (13.9)

8.3 (4.8)

40.1 (17.8)

9.3 (7.5)

6.8 (1.5)

4.0 (2.1)

6.2 (1.9)

4.2 (2.2)

a

Each fundamental need score represents an average of three questions.

All F values refer to significant ostracism vs. inclusion main effects.

c

Total mood score was an average of four 9-point bipolar questions.

d

This was a 9-point scale with rejected–accepted as anchors.

b

participants failed to perceive me as a worthy and likeable person,’’ ‘‘I felt somewhat inadequate during the

Cyberball game’’), and meaningful existence (‘‘I felt that

my performance [e.g., catching the ball, deciding whom

to throw the ball to] had some effect on the direction of

the game,’’ ‘‘I felt non-existent during the Cyberball

game,’’ ‘‘I felt as though my existence was meaningless

during the Cyberball game’’). Mood was assessed using

four bipolar questions (bad/good, happy/sad, tense/relaxed, and aroused/not aroused). The questionnaire also

contained two ancillary variables (‘‘I felt angry during

the Cyberball game’’ and ‘‘I enjoyed playing the Cyberball game’’). Unless otherwise stated, all questions

were rated on 9-point scales (where 1 ¼ not at all, and

9 ¼ very much so).

After the participants indicated that they had finished

the questionnaire, the experimenter asked participants

about their thoughts/feelings during the study, and

performed a verbal manipulation check by asking participants whether they had played the game with university students or computer players. They were then

thoroughly debriefed about the aims of the study,

thanked, and given course credit for participating in the

study.

Results

Manipulation checks. There were three manipulation

checks assessing inclusionary status. As shown in Table

1, participants in the ostracism condition reported that

they felt significantly less included and more rejected

than participants in the inclusion condition (smallest F

was for rejection, F ð1; 57Þ ¼ 24:3, p < :0001). Participants in the ostracism condition also reported that they

received the ball less often during the game than participants in the inclusion condition, F ð1; 58Þ ¼ 83:9,

p < :0001.2 This suggests that participants correctly

perceived whether they were included or ostracized

during the game.

To assess the source manipulation, a verbal manipulation check was carried out at the end of the study

prior to debriefing. All but two participants correctly

identified whether they played the game with computer

or human players. The two aberrant participants (both

in the human players condition) reported having played

the game with two computers rather than two humans.

2

Degrees of freedom vary slightly in the analyses here and in Study

2 because of occasional missing data.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

4

L. Zadro et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology xxx (2004) xxx–xxx

The game had malfunctioned during their participation

(a factor that may have led them to realize that they

could not have been playing with two humans). Consequently, their self-report data were not included in the

analysis.

Self-reported levels of needs. The items assessing the

four needs (state measures of belonging, control, selfesteem, and meaningful existence) were reverse scored

where necessary and the internal consistency of the items

assessing each need were examined. CronbachÕs alpha

coefficients for each need were: belonging ¼ 74; control ¼ 72; self-esteem ¼ 70; and meaningful existence ¼ 66. The coefficients suggested a reasonable level

of internal consistency for each need; thus the average

for the items assessing each need were used in the

analysis.

The main findings of this study, that ostracized participants reported lower levels of the needs independent

of the source, can be seen in Fig. 1 (which depicts a

composite score for the four conditions tested in this

study). Statistical analysis of each need (see Table 1 for

all descriptive statistics) revealed that ostracized participants reported lower levels on each of the four needs

measured, smallest F ð1; 57Þ ¼ 11:1, p ¼ :002, for selfesteem. There were no significant main effects for source

identity on self-reported needs, nor did the inclusionary

status interact with the source manipulation, all

F s < 1:4, ns.

Mood. The mood items were reverse scored where

necessary (so that a higher score ¼ more positive mood)

and an average mood score was calculated. There were

no significant main effects or interactions for mood, all

F s < 1:0, ns.

Ancillary variables. Ostracized participants reported

feeling angrier than included participants (see Table 1),

Fig. 1. Mean self-reported levels of combined needs of belonging,

control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence, as a function of inclusion or ostracism, and by either human or computer in Study 1.

F ð1; 58Þ ¼ 8:2, p ¼ :006. There was no main effect for

whether they played with humans or computers, but

there was a significant interaction, F ð1; 58Þ ¼ 4:7,

p ¼ :034, such that anger was higher only when they

were ostracized by the computer.

Ostracized participants reported enjoying the game

less compared with included participants, F ð1; 58Þ ¼

10:2, p ¼ :002. There was no significant main effect of

source identity, or interaction between inclusionary

status and source identity, for enjoyment of the game,

both F s < 1, ns.

Discussion

In Study 1, we found that compared to included

participants, ostracized participants reported lower levels on the state measures of the four needs. Moreover,

ostracized participants also reported feeling angrier and

enjoyed the game less than included participants. Contrary to our expectations, mood reports were not affected by ostracism. It should be noted, however, that

the literature to date is surprisingly inconsistent on the

effects of social exclusion on mood. That is, while some

have reported worsened mood following ostracism

(Williams, 2001) or rejection (Leary, Koch, & Hechenbleiker, 2001), others have failed to see an effect on

mood following social exclusion (Twenge, Baumeister,

Tice, & Stucke, 2001; Twenge, Catanese, & Baumeister,

2002).

Although the ostracism manipulation adversely affected participants in accordance with previous ostracism research, whether participants were ostracized by

humans or the computer had no effect on their self-reported need levels, or enjoyment of the game. Oddly

enough, the only impact that the human/computer manipulation had was the unexpected interaction showing

that being ostracized by a computer made participants

angrier than being ostracized by humans. Based on

comments made during the interviews it would seem

that this result was due to a violation of the basic assumption that the computer is a tool to serve humans

and hence should not deliberately act to distress or

alienate them. For example, one participant (who happened to be a computer programmer) stated that he felt

incredibly angry and frustrated during the game because

‘‘the computer is supposed to serve me. ItÕs not supposed

to reject me.’’

Why would individuals report lower levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence

when they have experienced ostracism in a 6-min game

of virtual ball toss, regardless of whether they were

playing with humans or a computer? We believe that

initial reactions to ostracism are, in BrewerÕs (2003)

terms, ‘‘deep,’’ rather than ‘‘high.’’ That is, it is our

position that ostracism has such adaptive significance

for humans that there is essentially an early warning

ARTICLE IN PRESS

L. Zadro et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology xxx (2004) xxx–xxx

system that is quick to perceive social exclusion and feel

the associated pain, so that the individual is motivated

to make changes that will eliminate the ostracism.

One potential problem with Study 1 is that participants were not asked to indicate on the post-experimental questionnaire whether they believed they were

playing the game with humans or computers. Although

we assessed their perceptions in a post-experimental

interview, it is possible that experimenter bias may have

influenced our perceptions of their answers. Thus, although we think this is rather implausible, it is possible

that participants simply did not attend to our instruction about who they were playing the ball game with,

and that is why we found no main effects or interactions

with the human/computer manipulation on the self-reported needs. That we found one interaction on the

measure of anger (in an unexpected direction, we might

add), argues against this criticism that participants were

not attentive to the human/computer manipulation;

however, it is possible that this interaction was spurious.

Therefore, in Study 2, we added explicit manipulation

checks to the post-experimental questionnaire assessing

the participantsÕ understanding of with whom they were

playing. In Study 2, we also extended the present experimental design by adding a third factor: perceived

choice of the source. It may well be that to feel threats to

the four needs an individual must attribute some sort of

sinister intent on the part of the sources (Kramer, 1994).

What if we told them that the players with whom they

were playing were following a script that had been

provided to them, and that they had no choice but to

throw the ball to the individual that the script indicated?

If the needs that are threatened by ostracism require

some higher level interpretation of the ostracism event,

then we would expect this manipulation to eliminate the

negative impact when participants viewed the ostracism

behavior of the sources as outside their control. If,

however, the fundamental needs are affected without

cognitive intervention, then manipulations aimed at reducing sinister attributions may have no impact at all.

Study 2

In Study 2, we examined whether providing an explicit and external reason for ostracism reduced its

negative impact. If ostracized individuals know that the

reason they are not being thrown the ball has nothing to

do with them personally, but rather the other participants (be they human or computer) are simply following

a script, will they still report reduced levels of the four

needs? If so, we believe this suggests that it is the perception of oneÕs own ostracism, not oneÕs understanding

of it, that is immediately threatening.

Thus, participants in Study 2 were either included or

ostracized from the Cyberball game by two human

5

players or two computer-generated players. In addition,

half of the participants were informed that the players

(whether human or computers) were playing Cyberball

according to a script given to them by the experimenter.

This script instructed the players to whom they were to

throw the ball every time it was their turn to play.

Study 2 also included self-report manipulation

checks to supplement the verbal manipulation checks

used in Study 1, and some additional questions were

asked to assess other aspects of the Cyberball

experience.

Method

Participants and design

Seventy-seven undergraduates (30 males, 41 female,

M age ¼ 19:6 years, SD ¼ 1:9) enrolled in introductory

psychology at the University of New South Wales were

randomly assigned to a 2 (inclusionary status: inclusion

vs. ostracism) 2 (source identity: computer generated

vs. university students) 2 (attribution of choice:

scripted vs. unscripted) between-S design.3 Participants

volunteered to take part in the experiment in exchange

for course credit.

Procedure

The experiment was conducted on eight versions (one

per condition) of an Internet website, which were identical to those used in Study 1 except for modifications to

the cover pages to accommodate the attribution of

choice manipulation. The ostracism/inclusion and

source identity manipulations were identical to those

used in Study 1.

Attribution of choice manipulation. In the scripted

conditions, the cover page instructed participants that

the other players (whether computer generated or human) would be playing the game according to a script,

and hence their actions were not spontaneous. In the

unscripted condition, participants were instructed that

the game was spontaneous and the players were free to

throw the ball to whomever they chose (in the case of the

computer-generated players, this spontaneous action

was explained by saying that the players would be

throwing the ball randomly). In all conditions, participants were reminded that they were free to throw the

ball to whomever they chose.

Dependent measures. The questionnaire was essentially the same as that used in Study 1, with the addition

of manipulation check for source identity (‘‘Did you

play the Cyberball game with: two students from Macquarie and Sydney University or two computer-generated players?’’) and attribution of choice (‘‘Was the

sequence of throws by Player 1 and Player 2 scripted/

3

Initially, 120 participants were recruited, but a computer virus

prevented 43 participants from any form of participation.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

6

L. Zadro et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology xxx (2004) xxx–xxx

Results

pre-programmed or spontaneous?’’). One additional

question was added to examine whether the manipulations led participants to feel emotionally hurt (‘‘My

feelings were hurt during the game’’).

After the participants completed the game, they were

directed to complete the post-study questionnaire.

Debriefing. As in the previous experiment, the experimenter asked participants to state whether they had

played the game with two human players or two computers, and whether or not the game had been scripted

or unscripted. The experimenter then fully debriefed

participants, ensuring that they were aware that they

were randomly assigned to conditions. Participants in

the ostracism condition were carefully debriefed about

all aspects of the game, and were given extra information about the nature of ostracism. After answering any

remaining questions, participants were then thanked

and dismissed.

Manipulation checks. As shown in Table 2 (where

means and standard deviations can be found for all

dependent variables), our manipulations were perceived

as intended. Participants in the ostracism condition reported that they felt less included than participants in

the inclusion condition, and more rejected, (smallest F

was for rejection, F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 25:6, p < :0005). They also

reported receiving the ball less often during the game

than included participants, F ð1; 66Þ ¼ 117:8, p < :0001

The source identity manipulation was also successful in

that only 2% of participants incorrectly identified the

identity of the players, and 4% of participants incorrectly identified the attribution of choice manipulation.

Because there was no computer malfunction that could

easily account for these incorrect reports, all participants were retained in the analyses.

Table 2

Means and standard deviations (in parenthesis) of variables in Study 2 (all scales 1 ¼ not at all to 9 ¼ very much so, unless otherwise stated)

Source

Human

Computer

Inclusion

Fundamental needsa

Belonging

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 74:8, p < :0005b

Control

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 55:0, p < :0005

Self-esteem

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 25:2, p < :0005

Meaningful existence

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 68:0, p < :0005

Moodc

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 6:2, p ¼ :015

Ancillary variables

I felt angry during the Cyberball game

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 13:2, p ¼ :001

I enjoyed playing the Cyberball game

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 22:2, p < :0005

My feelings were hurt during the

Cyberball game

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 8:3, p ¼ :005

Manipulation checks

To what extent were you included

by the participants during the game?

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 122:7, p < :0005

What percentage of throws did you

receive during the Cyberball game?

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 117:8, p < :0005

Rejected–acceptedd

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 25:6, p < :0005

a

Ostracism

Ostracism

Scripted

ðn ¼ 12Þ

Unscripted Scripted

ðn ¼ 8Þ

ðn ¼ 7Þ

Unscripted Scripted

ðn ¼ 11Þ

ðn ¼ 9Þ

Unscripted Scripted

ðn ¼ 10Þ

ðn ¼ 9Þ

Unscripted

ðn ¼ 11Þ

5.8 (1.5)

6.3 (2.0)

3.6 (1.9)

2.8 (1.2)

5.8 (1.6)

6.4 (1.4)

3.0 (1.4)

2.7 (1.3)

5.8 (1.6)

6.8 (2.2)

2.7 (.90)

3.2 (1.5)

4.7 (.98)

5.5 (2.3)

2.9 (.96)

3.2 (1.6)

6.9 (1.0)

7.6 (1.3)

6.1 (1.7)

5.1 (1.9)

6.3 (2.1)

7.7 (1.6)

4.5 (1.7)

5.4 (1.4)

6.1 (1.6)

7.6 (1.1)

2.8 (1.4)

3.6 (2.1)

5.7 (1.4)

6.2 (1.3)

3.7 (1.8)

3.7 (1.3)

6.8 (1.4)

6.7 (1.4)

6.1 (1.3)

6.0 (1.3)

7.0 (.80)

6.6 (1.8)

5.4 (1.7)

6.4 (.88)

1.8 (1.8)

2.0 (2.1)

2.1 (1.4)

2.8 (1.8)

2.2 (1.5)

1.0 (.00)

4.0 (2.2)

4.0 (2.2)

4.6 (2.3)

6.6 (1.8)

3.3 (1.5)

3.0 (1.7)

5.1 (1.8)

5.2 (2.2)

3.3 (2.2)

3.5 (1.8)

2.2 (2.4)

1.1 (.35)

1.1 (.38)

3.2 (2.2)

2.1 (1.8)

1.2 (.42)

4.3 (2.7)

3.0 (2.2)

6.2 (1.5)

6.9 (2.0)

2.4 (.53)

2.6 (1.5)

5.3 (1.7)

6.0 (1.9)

2.2 (.44)

2.6 (.69)

35.9 (14.2) 45.3 (15.0) 11.7 (8.5)

13.9 (8.2)

43.9 (7.7)

45.8 (13.9) 15.7 (9.1)

13.1 (4.6)

6.3 (1.8)

4.2 (2.0)

6.3 (1.9)

5.7 (2.6)

3.5 (1.9)

6.9 (2.2)

4.4 (2.1)

Each fundamental need score represents an average of three questions.

All F values refer to significant ostracism vs. inclusion main effects.

c

Total mood score was an average of four 9-point bipolar questions.

d

This was a 9-point scale with rejected–accepted as anchors.

b

Inclusion

3.4 (2.1)

ARTICLE IN PRESS

L. Zadro et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology xxx (2004) xxx–xxx

Self-reported level of needs. As in Study 1, the items

assessing each need were reverse scored where necessary

and the internal consistency of the items were assessed.

CronbachÕs alpha coefficients for each need were as

follows: belonging ¼ .71; control ¼ .80; self-esteem ¼ .76;

and meaningful existence ¼ .69. The coefficients suggested a reasonable level of internal consistency for each

need; thus the average for the items assessing each need

were used in the analysis.

As in the previous study, there were significant main

effects for inclusionary status on the four needs such that

participants who were ostracized reported lower levels

of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence than participants who were included in the game,

(smallest F was for self-esteem, F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 25:2,

p < :0005).

There were no significant main effects for source

identity on the primary needs (largest F was for control,

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 2:2, p ¼ :147).

Attribution of choice did not affect self-reported need

levels for belonging, control, or self-esteem, but there

was a marginally significant main effect for meaningful

existence, such that participants who believed the game

was unscripted (free choice) reported higher levels of

meaningful existence than participants who believed the

players were scripted, F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 3:9, p ¼ :052.

There was also a marginally significant interaction

between inclusionary status and source identity for

meaningful existence, F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 3:95, p ¼ :051. Follow

up analyses revealed that the effects of inclusion and ostracism on self-reported meaningful existence produced

more extreme differences when the sources were human

than when the sources were computers. No other two-way

interactions for the remaining needs were significant, nor

were there any significant three-way interactions.

Mood. The mood items were reverse scored where

necessary (so that a higher score equalled more positive

mood) and an average mood score was calculated.

Participants in the ostracism condition reported feeling

more negative during the game than participants in the

inclusion condition, F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 6:2, p ¼ :015. There were

no significant main effects for source identity or attribution of choice, nor were there any significant two or

three way interactions, all Fs < 1:5, ns.

Ancillary variables. There were several effects of inclusionary status on the ancillary variables. Specifically,

participants who were ostracized reported feeling angrier, more hurt, and that they enjoyed the game less

than participants who were included in the game,

(smallest F was for anger, F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 8:3, p ¼ :005).

There were no significant main effects for source

identity or attribution of choice on the ancillary variables.

There was a significant two-way interaction between

inclusionary status and source identity for anger,

F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 5:0, p ¼ :028. Follow up analyses revealed

that participants who were included were no more angry

7

if playing a computer or humans, but as in Study 1,

ostracized participants were angrier at being ostracized

by a computer than humans, F ð1; 34Þ ¼ 5:4, p ¼ :026.

No other two-way interactions were significant.

There was a significant three-way interaction for hurt

feelings, F ð1; 69Þ ¼ 4:0, p ¼ :049, which suggested that

when interacting with humans, participants reported

higher levels of hurt feelings only when they were ostracized by two players who had free choice as to whom

they could throw the ball. Participants who played the

computer, however, reported more hurt feelings simply

when they were ostracized, regardless of whether or not

the computer game had been scripted.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 largely replicated the findings

of Study 1. Once again, we found that ostracism resulted

in lower self-reported levels of four needs. However, in

Study 2 we also found that ostracism resulted in less

positive mood than did inclusion. Thus, the inconsistent

nature of mood effects following social exclusion that

exists in the broader literature was mirrored in our two

studies. We regard this inconsistency as evidence of the

less than robust effect of social exclusion on mood. In

any case, as Twenge et al. (2001, 2002) and Williams et

al. (2000) have also demonstrated, regardless of whether

mood is affected by social exclusion, it does not mediate

need levels nor subsequent behaviors.

More importantly for the present investigation, ostracism by computers was just as unpleasant as ostracism by humans, and furthermore, it did not matter

whether the human or computer players were perceived

to have a choice as to whom they threw the ball. Thus,

once again, it appears that ostracism, per se, is felt immediately as a negative and depleting experience. ParticipantsÕ initial reactions to a short exposure to

ostracism were not affected by two factors that would

generally be regarded as rendering the ostracism experience meaningless: being ignored and excluded by a

computer, and knowing that the players were told (or

programmed) not to throw the ball to them. Instead,

within minutes, feelings of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence are reduced, simply because the participants were not thrown a ball while

playing a relatively meaningless game that had no winners or losers, with people who they do not know and

will not meet.4

4

As one reviewer suggested, it is possible that participants viewed

the scripted conditions as an attempt to ostracize them by the

experiment. Although we do not have any measures to explicitly

address this possibility, this suggestion would lead to an expectation of

stronger effects under the scripted conditions (for human or computer

sources), which we did not find.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

8

L. Zadro et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology xxx (2004) xxx–xxx

General discussion

The findings of both studies lead us to conclude that

ostracism is such an important warning signal that individuals are pre-cognitively attuned to its employment

on them. For primates, and many other species (see

Williams, 2001), ostracism means death. For humans, it

surely signals the potential for hard times, possibly loss

of contact with important others, loss of resources, and

in some cases, death. Hence, it appears that even the

slightest hint of ostracism, in the present case by a

computer, is enough to trip off emotional reactions that

will activate coping strategies to increase oneÕs subsequent inclusion.

Our finding that individuals can react to computers in

a similar fashion to how they react to humans is also

consistent with NassÕs work on human–computer interactions (e.g., Reeves & Nass, 1996). In a variety of

clever studies, Nass and his colleagues have shown that

humans will reciprocate self-disclosures, be more strategically polite, and form in-group alliances with computers, just as they have been shown to do with other

people. Whether this means that we anthropomorphize

computers, enact mindless scripts to guide our social

behaviors, or that we have such a deep-rooted need to

belong that it can be fulfilled by computers (as exemplified in Steven SpielbergÕs AI where the mother grew to

love a Cyborg son), is the subject matter for future investigations.

We remain motivated to find conditions that involve

ignoring and exclusion but that are so minimal as to not

inflict emotional damage. Based on the present findings,

it appears that this search for the necessary and sufficient conditions for ostracism, at least when measured

during or soon after the ostracism, may be difficult or

impossible. It appears that ostracism is such a powerful

signal that even being ignored by a computer can activate strong reactions. Indeed, Eisenberger, Lieberman,

and Williams (2003) showed activation of the anterior

cingulate cortex—the brain region that is also activated

when individuals endure physical pain—as a result of

Cyberball ostracism, even when the participants were

told their particular computer was not yet linked to the

other two participantsÕ computers. We are also examining the impact of these simple acts of ostracism on

participantsÕ cardiovascular responses (Zadro, Barker,

Richardson, & Williams, 2001; Zadro, Walker, Williams, & Richardson, 2000). The amassed evidence

suggests that at all levels of measurement, humans detect and suffer from the most minimal cues of ostracism,

supporting our view that ostracism is such a powerful

social signal that it produces widespread intrapsychic

reactions that serve to mobilize coping responses (see

also, Panksepp, 2003).

References

Brewer, M. (2003). Implicit and explicit processes in social judgments

and decisions: An integration. In J. P. Forgas, K. D. Williams, &

W. von Hippel (Eds.), Responding to the social world: Implicit and

explicit processes in social judgments and decisions. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Eisenberger, N. A., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does

rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302,

290–292.

Kramer, R. M. (1994). The sinister attribution error: Paranoid

cognition and collective distrust in groups and organizations.

Motivation and Emotion, 18, 199–229.

Leary, M. R., Koch, E. J., & Hechenbleiker, N. R. (2001). Emotional

responses to interpersonal rejection. In M. R. Leary (Ed.),

Interpersonal rejection (pp. 145–166). New York: Oxford University Press.

Leary, M., Kowalski, R. M., Smith, L., & Phillips, S. (2003). Teasing,

rejection, and violence: Case studies of the school shootings.

Aggressive Behavior, 29, 202–214.

Panksepp, J. (2003). Feeling the pain of social loss. Science, 302, 237–

239.

Reeves, B., & Nass, C. (1996). The media equation: How people treat

computers, television, and new media like real people and places.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Twenge, J. M., Baumeister, R. F., Tice, D. M., & Stucke, T. S. (2001).

If you canÕt join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on

aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

81, 1058–1069.

Twenge, J. M., Catanese, K. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2002). Social

exclusion causes self-defeating behavior. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 83, 606–615.

Williams, K. D. (1997). Social ostracism. In R. M. Kowalski (Ed.),

Aversive interpersonal behaviors (pp. 133–170). New York: Plenum.

Williams, K. D. (2001). Ostracism: The power of silence. New York:

Guilford Press.

Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K. T., & Choi, W. (2000). CyberOstracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 748–762.

Williams, K. D., Govan, C. L., Croker, V., Tynan, D., Cruickshank,

M., & Lam, A. (2002). Investigations into differences between

social and cyber ostracism. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, &

Practice, 6, 65–77.

Williams, K. D., & Zadro, L. (2001). Ostracism: On being ignored,

excluded and rejected. In M. R. Leary (Ed.), Interpersonal rejection

(pp. 21–53). New York: Oxford University Press.

Zadro, L., Barker, G. L., Richardson, R., & Williams, K. D. (2001).

Physiological impact of ostracism: Challenge and threat. Presented

at the 73rd Annual Meeting of the Midwestern Psychological

Association. Chicago, Illinois.

Zadro, L., Walker, P., Williams, K., & Richardson, R. (2000). The

psychophysiological effects of being ostracized. Presented at the 10th

World Congress of Psychophysiology, Sydney.