A Prosperity Grid for North Carolina

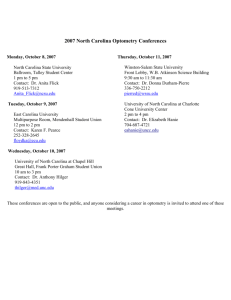

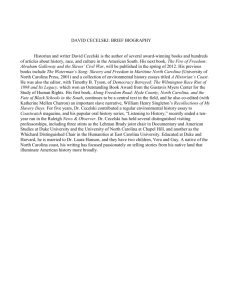

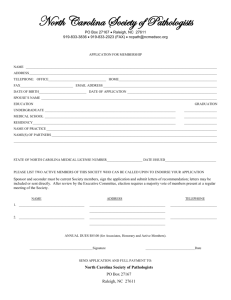

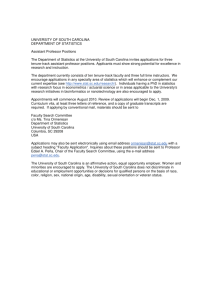

advertisement