CASE - STARBUCKS

advertisement

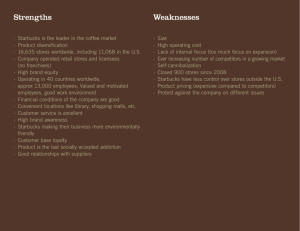

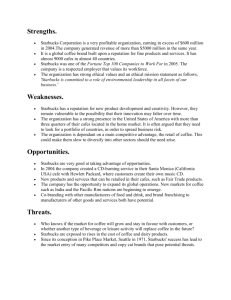

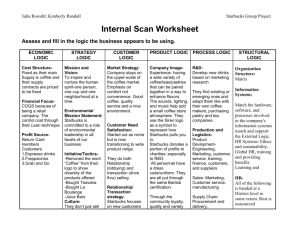

CASE - STARBUCKS For use only by IBAcc Competition Committee 2014 The History of “Starbucks” If the rise of Starbucks from a single Seattle coffee store to the world‟s biggest supplier of coffee drinks is now part of the mythology of American entrepreneurial capitalism, the story of its guiding genius, Howard Schultz, fits a much older folkore, that of “the hero‟s return”. After lifting Starbucks from obscurity to become one of the wold‟s most successful service corporations, Schlutz stepped down from the CEO position in 2000. By 2007, Starbucks‟ performance was flagging: margins and same-store sales were both in decline. Amidst fears of market saturation, increasing competition, and depressed consumer expenditure, Starbucks‟ fortunes were restored. Growth had been rekindled, operating profits and margins hit new records, and on April 13, 2012, Starbucks‟ shares closed at an all-time high of $62, up from $10 in March 2009. The rise of Starbucks from a single store in Seattle‟s Pike Place Market to a Fortune 500 company (number 229 on Fortune‟s 2012 listing) is an exemplary tale of American entrepreneurship. When Starbucks was founded in 1971, coffee consumption in the United States had been on the decline for nearly a decade. Most American Coffee drinkers drank home-brewed Folgers, Maxwell House, or Nescafe-grocery store brands of light roast coffee with the smooth flvor generally preferred by Americans. Away from home, they ordered coffee with a meal at a diner or restaurant, or on the go from a fast food outlet, convenience store, or gas station. However, in a few neighborhoods in San Fransisco and New York, small local coffeehouses and specialty coffee roasters such as Peet‟s had recently been established. Starbucks was created in this mold with the aim to roast and sell great coffee. By 1982, Starbucks had five retail outlets that sold beans and supplies for brewing coffee at home, but not prepared beverages. It also had a roasting facility and a wholesale business. This growth attracted the attention of Schultz, then the vice president of the American subsidiary of Hammarplast, a Swedish housewares company that made plastic cone coffee filters for home coffee brewing. Schultz went to Seattle to find out why a small company called Starbucks ordered more of these filters than any other customer. He liked what he found and joined Starbucks later that year as director of retail operations. During a business trip to Milan, Italy, the following year, Schultz was struck by the city‟s ubiquitous espresso bars. The bars served well-prepared espresso and brewed coffee and were important places for conversation and socializing. Schultz realized that America lacked similar places offering high-quality coffee in a comfortable setting for meeting and relaxing. He left Milan with a determination to create such an establishment in America. Schultz later dubbed this “the third place” beyond home and work, a term he borrowed from The Great, Good Place, a book in which sociologist Ray Oldenburg laments the decline of traditional American community meeting places like country stores and soda fountains. Starbucks‟ management, however, was not receptive to the idea of selling epresso, espresso-based drinks such as cappucino, and food items within six months, prompting Shlutz to open two more locations. Despite his success, Schultz faced skepticism from investorswhen he was trying to raise $1.25 million to fund his expansion, Schultz was turned down by 217 of the 242 potential investors he approached, many of whom expressed concern that he had no patent on his dark roast, no special access to coffee beans, and no way to prevent someone else from imitating his concept. In 1987 Il Giornale acquired Starbucks, including its retail outlets, coffee roasting facilities, and wholesale operation. Schultz rebranded the existing stores with the Starbucks name. The first Il Giornale had been a virtual copy of a Milanese espresso bar, complete with bow-tied waiters, a stand-up coffee bar, and sleek European furniture. By contrast, the new Starbucks-branded locations were decorated in earth tones with overstuffed chairs, wood floors and cozy fireplaces the encouraged patrons to linger and relax. Starbucks coffee was different from the coffee most Americans were used to consuming. In addition to being much more expensive, Starbucks coffee had a taste unlike typical American coffee. Starbucks roasted its beans in its own carefully controlled facility, where they were given a robust European-style flavor derisively called “Charbucks” by some, and then shipped them whole to its stores where they were ground immediately before brewing to ensure maximum freshness, flavor, and aroma. Starbucks espresso drinks were also prepared in a different way : a barista, a master of both the art and science of coffee production, “pulled” shots of espresso by hand using a La Marzocco machine, steamed milk to just the right temperature, and scooped elegant dollops of foam for cappucinos, all while chatting with customers about the different varieties of Starbucks coffee. In a nod to the heart of coffee culture, Starbucks invented a quasi-Italian lingo for its drink sizes (short, tall, grande, and vent) and the drinks themselves (e.g., Caramel Macchiato and Frappuccino). No matter how a customer ordered, counter clerks were trained to repeat the order using the correct terms in the Starbucks-specified order. Their tone was described as “not one of rebuke, but nevertheless most customers learn to avoid the implied correction by stating their order right is an aspiration, a small victory on the way to the office. By 1996, the Starbucks mermaid logo appeared on more than 1,000 stores. Starbicks selected its locations carefully, targeting areas with large numbers of wealthy and highly educated professional workers. These were the new American elite-dubbed “ bobos” (bourgeois bohemians) by commentator David Brooks-who used consumption as a way to distinguish themselves from the less enlightened masses. Soon, more and more American consumers aspired to emulate the coffee drinkers that were first attracted to Starbucks. “Customers believed that their grande lattes demonstrated that they were better than others-cooler, richer, and more sophisticated. As long as they could get all of this for the price of a cup of coffee, even an inflated one, they eagerly handed over their money, three and four dollars at a clip. ”As Roly Morris, one of the team that helped bring Starbucks to Canada, observed, “We‟re offering a lifestyle product...that transcends the usual barrier. May be you can‟t swing a Beamer (BMW)...but most people can treat themselves to a great cup of coffee. Starbucks Expands (1996-2006) Beginning in 1996 Starbucks embarked on a significant wave of growth by concurrently executing two initiatives : (1) selling Starbucks products through mass distribution channels, and (2) dramatically expanding its retail footprint. Schultz played an important role in both initiatives, first as CEO until 2000, and thereafter as chairman and chief global strategist. Selling Through Mass Distribution Channels The first product Starbucks sold through mass distribution channels in the United States was its bottled Frappuccino coffee drink, brought to market through a joint venture in 1996 with Pepsi-Cola North America. The arrangement drew on Pepsi‟s expertise in managing store supply and demand but allowed Starbucks to retain control over the developmentand sale of its products.Around the same time, the company partnered with Dreyer‟s to produce a premium coffee-flavored ice cream. Soon after, Starbucks began to test market Starbucks-branded coffee beans and ground specialty coffee in grocery stores and supermarkets. In 1998, approximately a year after market testing, Starbucks coffee was on the shelf in approximately 3,500 supermrkets in ten West Coast cities. By 1996 Starbucks had opened just over 1,000 stores. Within five years, that number had grown to nearly 5,000. In 2007 Starbucks operated 15,000 stores and in the same year publicly announced a goal to open 40,000 locations worldwide, with 20,000 in the United States alone. (In the same year, McDonald‟s operated approximately 14,000 restaurants in the United States and 31,000 locations worldwide. The Rise of Competitor (2006-2008) The expansion of Starbucks was good for the coffeehouse industry in the United Stated, a phenomenon dubbed the “Starbucks Effect” By 2006 there were approximately 24,000 specialty coffee establishments in the United States, nearly 60% of which were independently owned and operated(having three or fewer outlets). Starbucks also found itself competing against smaller chains that resembled preexpansion Starbucks stores, complete with manual espresso machines and hand-scooped coffee. These chains-including Peet‟s coffee dan tea (which featured La Marzoco namual espresso machine in many stores), the Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf and Caribou Coffee-operated between 150 and 500 stores, but customers seemed to perceive them more like independent coffeehouses. When Caribou Coffee was forced to close in Ann Arbor, Michigan, as a result of escalating rent, one patron claimed it was “like the end of Ann Arbor.” By contrast, Starbucks was often perceived as a hearthless corporate predator. As one observer noted, “For a growing slice of the population, “Wal-Mart,‟ „Starbucks‟ and „chain‟ have become dirty words, while local, independent and unique have become core values.” Similiar to independent coffee retailers, those small chains charged prices about 10% higher than Starbucks location in the same geographic area. PREMIUM PRICE Schultz Return as CEO (2008) As 2008 dawned, Starbucks was in crisis: financial results from the previous quarter were the worst in its history as a public company. On January 7, Schultz returned to Starbucks as CEO at the request of the board of directors. He immediately announced a “transformational agenda” of strategic initiatives to revitalize the company with which he was so closely identified. Closing underperforming stores was part of a broader strategy aimed at reducing operating costs. Through a combination of procurement savings, improved logistics, reduced operations waste, and labor cost savings, Starbucks cut $580 million in operating costs in 2009. The revamped supply chain operations delivered 90% of store orders on time and without errors. While he was closing underperforming stores and improving the supply chain, Schultz undertook several smaller initiatives, including introducing new low-profile but still semiautomatic espresso machines; offering free refills on same-day purchases; and returning to instore coffee grinding. Schultz also took the very public step of closing all Starbucks company owned stores for an afternoon to retrain all baristas in the production of espresso-based drinks. During this time, Starbucks also introduced a new roast of coffee, Pike Place Roast. Previously, Starbucks had offered rotating selection of coffee bean/roast combinations, such as French Roast, Sumatra, or Kenyan. This meant that a Starbucks tall drip coffee could taste dramatically different on different days or in different stores. Customers that did not know Starbucks rotated its coffees attributed the difference to operational inconsistencies. The new roast, whose flavor was described as “round, smooth, and balanced” with a “mild, sweet finish,”was offered every day as the Starbucks “default” coffee alongside a bolder-flavored option. Starbucks Pursues New Growth Initiatives (2009-2011) Starting in 2009 Starbucks undertook three new growth initiatives outside of its retail coffeehouse presence. First, it made several moves to expand its presence in the”away from the store” coffee market. Second, it pursued coffee initiatives outside of the Starbucks brand. Finally, Starbucks acquired a supplier that moved it into the business of manufacturing highend coffee brewing equipment. Starbucks had been experimenting with instant coffee since 1989, when it was approach by Don Valencia, a cell biologist who had developed an innovative method for freeze-drying cells for examination under a microscope. Valencia had developed a way to apply the technique to coffee beans, which enabled him to carry high-quality coffee on long hiking trips. After being hired by Starbucks to create a commercially viable version of his technique, Valencia first created a powdered coffee extract that was critical to the creation of a shelf-stable Frappuccino, a Starbucks ice cream created with Dreyers‟s and Double Black Stout, a coffee-and-beer combination product from Redhook Ale Brewery. In late 2009 Starbucks launched the culmination of Valencia‟s research : Starbucks VIA, a water-soluble coffee offered in single-serve packages or “sticks.” Even though instant coffee represented a $20 billion market worldwide, analysts were skeptical about the company‟s chances in the category, which accounted for $700 million in sales in the United States, or about 8% of the overall market. This external skepticism was matched by internal resistance and hesitancy among partners (the Starbucks term for employees) because instant coffee was perceived to be a “down-market” category. VIA was priced at about $1 per 3 oz (85g) stick. This price was two-thirds the price of a cup of Starbucks in-store coffee, but three to ten times the price per serving of other instant brands, most of which cost less than twenty cents per serving. In March 2011, Coffe Review conducted a blind taste test of VIA and competing instant coffee brands that showed price and appeal were not closely correlated. Despite its high price, the taste of Starbucks Colombia VIA was ranked below the lower priced Nescafe Taster‟s Choice 100% Colombian. The result were even more striking for Italian Roast VIA, which was ranked seventh in taste, scoring below Trader Joe‟s Colombia Instant Coffee despite a per-serving price ten times higher. After one year, global sales of VIA topped $135 million. This made it the number five instant coffee brand by volume in the United States, taking share from other brands, including market leader Folgers instant. That same year, the instant coffee category grew 15% after declines in three of the previous four years. In addition, to growing its presence in the “away from the store” coffee market, Schultz also focused on developing non-Starbucks branded businesses. In July 2009 Starbucks opened 15th Avenue Coffee and Tea in Seattle, followed closely by Roy Street Coffee and Tea. Both stores served espresso drinks made with the La Marzocco machine used in the original Starbucks stores and offered multiple options for brewing coffee by the cup, including manual pour-over, French press, Synesso, and Clover drip coffe machines. The decor featured recovered furniture, and the menu offered select small-batch micro-roasted coffe along with beer, wine, and made-to-order food items. The stores offered Starbucks coffee and Tazo tea and delivered “the same high quality with the same heart in a new way.” Some customers protested that the stores were a deliberate attempt by the company to deceive them. Starbucks also announced it would grow its Seattle‟s Best Coffee brand into a multibillion dollar “approachable” premium coffee using the tagline “Great Coffee Everywhere.” The brand had been acquired by Starbucks in 2003 along with its fifty stores and its large supermarket business, which included a strong presence in the profitable flavored beans category-a category Starbucks had never entered. Seattle‟s Best president Michelle Gass described Starbucks as a destination coffee experience” and Seattle‟s Best as Coffee “brought to the consumer when they make other retail choices.” Starbucks’ Strategy Starbucks‟ strategy was grounded in its mission “to inspire and nurture the human spirit-one person, one cup and one neighborhood at a time.” To put this mission into practice required Starbucks to not just serve excellent coffee but also engage its customers at an emotional level. As Schultz expained: “We‟re not in the coffee business serving people, we are in the people business serving coffee.” Central to the Starbucks‟ strategy was Schultz concept of the “Starbucks Experience,” which centered on the creation of a “third place”-somewhere other than home and work where people could engage socially while enjoying the shared experience of drinking good coffee. The Starbucks Experience combined several elements: Coffee beans of a high, consistent quality and the careful management of a chain of activities that resulted in their transformation into the best possible espresso coffee: “We‟re passionate about ethically sourcing the finest coffee beans, roasting them with great care, and improving the lives of the people who grow them.”. Employee involvement. The counter staff at Starbucks stores-the baristas-played a central role in creating and sustaining the Starbucks Experience. Their role was not only to brew and serve coffee but to engage customers in the unique ambiance of the Starbucks coffee shop. Starbucks‟ human resource practices were based upon a distinctive view about the company‟s relationship with its employees. If Starbucks was to engage customers in an experience which extended beyond the provision of good coffee, then it was going to have to employ the right store employees who would be the critical providers of this experience. This required employees who were commited and enthusiastic communicators of the principles and values of Starbucks. This in turn required the company to regard its employees as business partners. Starbucks‟ human resource practice were tailored, first, to attracting and recruiting people whose attitudes and personalities were consistent with the culture of the company and, second, to foster trust, loyalty, and a sense of belonging, which would, in turn, facilitate their engagement with the Starbucks‟ experience. Starbucks selected employees with care and rigor, placing a heavy emphasis on adaptability, dependability, capacity for teamwork, and willingness to further Starbucks principles and mission. Its training program extended beyond basic operational and customer service skills and placed particular emphasis on eduvating employees about coffee. Unique among catering chains, Starbucks provided health insurance for almost all regular employees, including part-timers. Community relations and social purpose. Schultz viewed Starbucks as part of a broader vision of common humanity: “I wanted to build the kind of company my father never had the chance to work for, where you would be valued and respected whatever your level of education. Offering healthcare was a transforming event in the equity of the Starbucks brand that created unbelievable trus among our people. We wanted to build a company that linked shareholder value to the cultural values that we want to create with our people.” Schultz‟s vision was of a company that would earn good profits but would would also do good in the world. This began at the local level: “Every store is part of a community, and we take our responsibility to be good neighbors seriously. We want to be invited in wherever we do business. We can be a force for positive action-bringing together our partners, customers, and the community to contribute every day.” It extended to Starbuck‟s global role: “we have the opportunity to be a different type of global company. One that makes a profit but at the same time demonstrates a social conscience.” The layout and design of Starbucks stores were seen as critical elements of the experience. Starbucks has a store design group that is responsible for the design of the furniture, fittings, and layout of Starbucks‟ retail outlets. Like everything else at Starbucks, store design is subject to meticulous analysis and planning, following Schultz‟s dictum that “retail is detail.” While every Starbucks store is adapted to reflect its unique neighborhood, “there is a subliminal unifying theme to all the stores that ties into the company‟s history an mission-“back to nature” without the laid-back attitude; community-minded without stapled manifestos on the walls. The design of a Starbucks store is intended to provide both unhurried sociability and efficiency on the run, an appreciation for natural goodness of coffee and the artistry that grabs you even before the aroma. This approach is reflected in the designers‟ generous employment of natural woods and richly layered, earthy colors along with judicious high-tech accessorizing...No matter how individual the store, overall store design seems to correspond closely to the company‟s first and evolving influences: the clean, unadulterated crispness of the Pacific Northwest combined with the urban suavity of an espresso bar in Millan.” Starbucks‟ location strategy-its clustering of 20 or more stores in each urban hub-was viewed as enhancing the experience both in creating a local “Starbucks buzz” and in facilitating loyalty by Starbucks‟ customers. Starbucks‟ analysis of sales by individual store found little evidence that closely located Starbucks stores cannibalized one another‟s sales. To expand sales of coffee-to-go, Starbucks began adding drive-through windows to some of its stores and building new stores adjacent to major highways. Looking Ahead The release of Starbucks quarterly financial results on April 26, 2012 offered further confirmation of the strength of Starbucks‟ recovery under Schultz‟s leadership and reinforced the view that the downturn of 2007/2008 had been an aberration resulting from Starbuck‟s overeager pursuit of growth. Yet amidst the acclaim for Schultz‟s remarkable success in returning Starbucks profitability and growth, many of the concern that had worried investment analysts in 2008 had not disappeared: the US recovery and the world economy remained fragile and the competitive forces that had threatened Starbucks in 2008 appeared even stronger in 2012. Some had doubts about the consistency and coherence of Starbucks‟ strategy. After refocusing Starbucks on its core values and core identity, might Schultz‟s multiple initiatives be a distraction for the company? For those who had perceived an uneasy relationship between Starbucks‟ claim to be providing authentic, gourmet coffee and its offerings of syrup-flavored coffees, the introduction of instant coffee was viewed as brand-threatening. Starbuck‟s push into the grocery trade was taking the company into an intensely competitive field where it would need to develop new capabilities. Barclays Capital analyst Jeff Bernstein commented, “They‟re starting a new chapter from scratch. While viewed favorably by most, the question has to be: Do you realize the agnitude of the task you‟re taking on?” Leadership Performance: According to leadership theories, there are many styles of leaders to be used in order to achieve the excellence organization performance. Some theories and model that introduced and growth over 70 years namely: Trait Approach of Leadership, The Behavioral School, The Contingency or Situational School, Leader and Followers model. One of leadership style that interesting to correlate with culture is Transformational Leadership. James MacGregor Burns (1978) is the one who first introduce about transformational leadership theory. Burns define transformational leadership as “a relationship of mutual stimulation and elevation that converts followers into leaders and may convert leaders into moral agents”. Burns injected the humanistic psychology factors into leadership theory. Bernard Bass is the next researcher who developed Burns‟ concept of transforming leadership. According to Bass and Avolio (1994) “Transformational Leadership is closer to the prototype of leadership that people have in mind when they describe their ideal leader, and it is more likely to provide a role model with which subordinates want to identify”. Furthermore, they said that there are four indicators of Transformational Leadership, with acronym 4I‟s: Individualized Consideration, Intellectual Stimulation, Inspirational Motivation and Idealized Influence. Speaking of Starbucks, there are four facts that show us the transformational leadership of Schultz: 1. He is Individualized Consideration, it means have feeling of empathy and listening. Schultz says that “if you treat people like family you will make them loyal and encourage them to give their all”. 2. He is Intellectual Stimulation, it means questioning. Schultz says that “we are not in the coffee business serving people, we are in the people business serving coffee”. 3. He is Inspirational Motivation. Schultz inspired his employee for an active action, bring together partners, customers, and the community to contribute, tend to Starbucks global role. 4. He is Idealized Influence. Schultz cut his own salary as confidence in his action of minimizing the operational costs. He did this once he back at 2008, since the performance of Starbucks is going decrease and going bad. After he returned, Shultz need one year and half to put Starbucks back again on its excellence position. The action of cut his own salary is the strong communication of Schultz to all the people (employee and customer), to show about the sense of urgency for change. In Schultz perspective, people are the fundamental of business performance. This paradigm is same with another phenomenal concept such as transformational leadership or Balance Scorecard framework. According to Kaplan - the professor from Harvard University and the man who invented Balance Scorecard - the fundamental of financial result is the employee and customer. Employee and customer is about the people, as Schultz view Starbucks as “people business serving coffee”. “People business” is really the core culture in Starbucks. Schultz always tries to communicate that culture in every opportunity with his employee (training and annual leadership meeting) and customer. Definitely, customer is only about the buyer, but they also included the community and the citizens. The facts we can notice that Starbucks participate in community project (cleanup and restoration after Hurricane Katrina), launching Starbucks Shared Planet and “My Starbucks Idea”. Those activities make Starbucks or Schultz got some award regarding corporate responsibility: 2000-2012: one of the “100 best corporate citizens” 2009-2011: most ethical company 2011-2012: Sustainability design award =============================================================== EXHIBIT 1 (Revenue of Starbucks, in millions) EXHIBIT 2 (Starbuck‟s Stock Price, Feb 7th 2014)