A Cause Denied, 1864-1865

advertisement

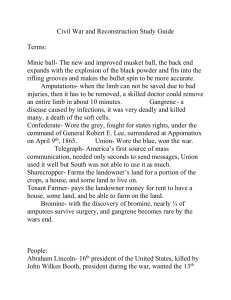

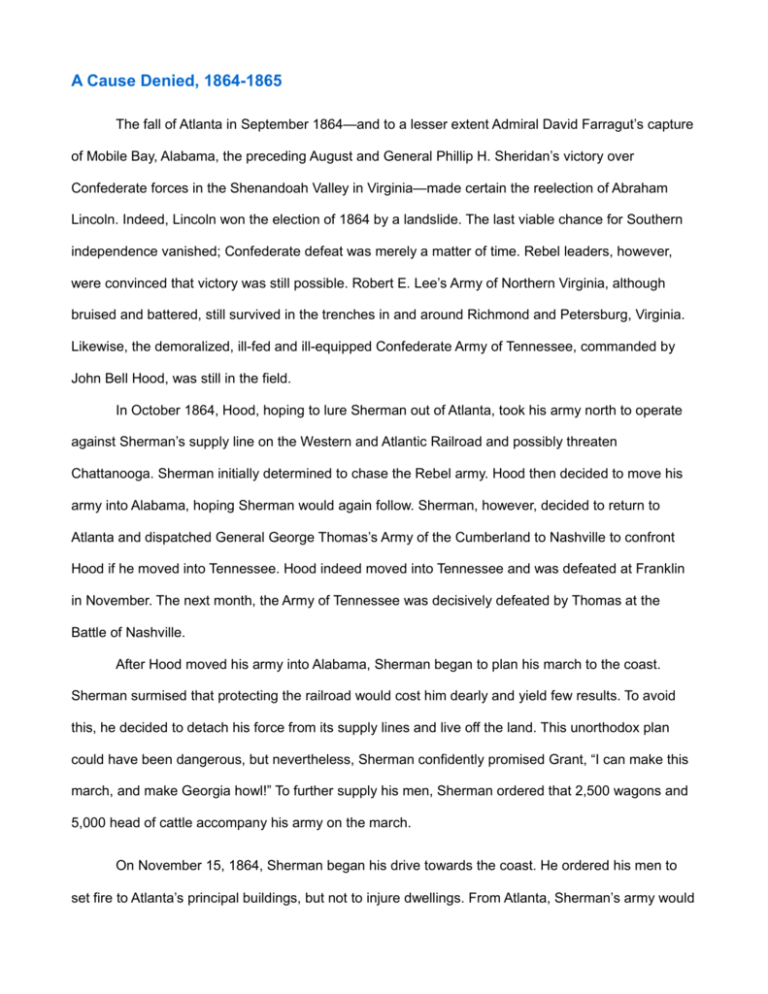

A Cause Denied, 1864-1865 The fall of Atlanta in September 1864—and to a lesser extent Admiral David Farragut’s capture of Mobile Bay, Alabama, the preceding August and General Phillip H. Sheridan’s victory over Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia—made certain the reelection of Abraham Lincoln. Indeed, Lincoln won the election of 1864 by a landslide. The last viable chance for Southern independence vanished; Confederate defeat was merely a matter of time. Rebel leaders, however, were convinced that victory was still possible. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, although bruised and battered, still survived in the trenches in and around Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia. Likewise, the demoralized, ill-fed and ill-equipped Confederate Army of Tennessee, commanded by John Bell Hood, was still in the field. In October 1864, Hood, hoping to lure Sherman out of Atlanta, took his army north to operate against Sherman’s supply line on the Western and Atlantic Railroad and possibly threaten Chattanooga. Sherman initially determined to chase the Rebel army. Hood then decided to move his army into Alabama, hoping Sherman would again follow. Sherman, however, decided to return to Atlanta and dispatched General George Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland to Nashville to confront Hood if he moved into Tennessee. Hood indeed moved into Tennessee and was defeated at Franklin in November. The next month, the Army of Tennessee was decisively defeated by Thomas at the Battle of Nashville. After Hood moved his army into Alabama, Sherman began to plan his march to the coast. Sherman surmised that protecting the railroad would cost him dearly and yield few results. To avoid this, he decided to detach his force from its supply lines and live off the land. This unorthodox plan could have been dangerous, but nevertheless, Sherman confidently promised Grant, “I can make this march, and make Georgia howl!” To further supply his men, Sherman ordered that 2,500 wagons and 5,000 head of cattle accompany his army on the march. On November 15, 1864, Sherman began his drive towards the coast. He ordered his men to set fire to Atlanta’s principal buildings, but not to injure dwellings. From Atlanta, Sherman’s army would carve a sixty-mile-wide swath of destruction through the heart of Georgia. To allow for a quicker march, he divided his army into two wings: the right commanded by Major General Oliver O. Howard and the left commanded by Major General Henry W. Slocum. Howard’s and Slocum’s wings initially headed for Macon and Augusta, respectively, before changing course so as to occupy the state capital of Milledgeville, which surrendered on November 23. Confederate authorities were virtually powerless to halt Sherman’s advance. Hardee was in overall command of Southern forces in Georgia. However, with only 8,000 cavalrymen under Joseph Wheeler and scattered state militia at his disposal, there was little he could do. Wheeler’s men often did more harm than good by plundering the property of loyal Confederate civilians. One Georgia planter referred to Wheeler’s command as a “plundering band of horse stealing ruffians.” The marauding of Wheeler’s cavalry often equaled the depredations of Sherman’s men, despite the latter’s notoriety. Although Wheeler’s cavalry harassed Sherman’s columns and portions of Rebel infantry made brave, yet futile, stands against the Union juggernaut, by December 10, Sherman’s army was outside Savannah. Fort McAllister on the Ogeechee River, however, prevented the commander from linking up with the Union navy. Not wanting to besiege Savannah without the support of the navy, Sherman dispatched a portion of his command to capture the fort. The small Rebel garrison at Fort McAllister surrendered on December 13. With the added support of the Union navy, Sherman was confident that he could shell Savannah into submission. He sent a letter to Confederate General Hardee requesting the surrender of the city. Sherman assured Hardee that he was “prepared to grant liberal terms to the inhabitants and garrison.” However, if Hardee resisted, Sherman warned that his army was “burning to avenge the national wrong which they attach to Savannah and other large cities which have been so prominent in dragging our country into civil war.” Hardee, now seeing that his situation was hopeless, ordered the city of Savannah to be evacuated. Hardee and his army withdrew to South Carolina, leaving the mayor of Savannah to surrender the city on December 21. After Union forces occupied Savannah, one of the city’s African American inhabitants exulted, “Glory be to God, we are free!” Three days after the fall of Savannah, Sherman sent a letter to Major General Henry W. Halleck, the Chief of Staff, stating that “we are not only fighting armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies. I know that this recent movement of mine through Georgia has had a wonderful effect in this respect.” Indeed, Sherman’s March to the Sea, more than any other campaign of the war, convinced Southern civilians of the futility of further conflict. It also showed that by this stage in the Civil War, Confederate authorities were powerless to protect their civilians from the Union war machine. Sherman’s forces stayed in Savannah for a month before marching into South Carolina. While Sherman’s men were continuing their destructive drive in the Carolinas, Union General George Thomas in Nashville ordered for a cavalry raid into Alabama and central Georgia. These Union cavalrymen, commanded by General James Harrison Wilson, moved south through the center of Alabama, capturing Selma and Montgomery before swinging eastward into Georgia to capture Columbus—a major center of industry. A motley assortment of Southern troops—mainly state militiamen—under the command of General Howell Cobb defended Columbus. Even though they burned some of the bridges leading into the city, the Confederates were unable to hold back Wilson’s troops, and Columbus fell to the Union on April 16, 1865. After Wilson’s men destroyed anything of military value in Columbus, they set out for Macon, which was surrendered on April 20. On May 3, Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown surrendered all the forces under his command to Wilson. One week later, men under Wilson’s command captured Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Irwinville, Georgia. A month prior, Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Ulysses. S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, and on April 26, Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to William T. Sherman at Bennett Farm in North Carolina. In early May, the last Confederate forces east of the Mississippi River surrendered. Although some Confederate troops east of the Mississippi River remained in the field, the Civil War was over.