The Demographics of the US Equine Population

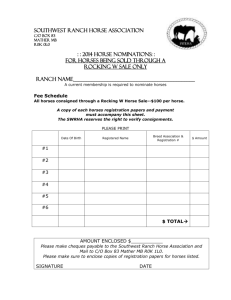

advertisement