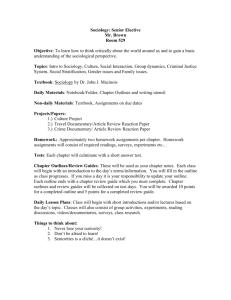

MEDICAL SOCIOLOGY: PRINCIPLES, PRACTICES, AND PUZZLES

SYO 4402, Section 02, Spring 2014

Monday & Wednesday, 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm, Room 214 HCB

Instructor: Xan Nowakowski, PhD, MPH

E-mail: xnowakowski@fsu.edu

Office: College of Medicine, Room 3300D

Phone: (850) 645-7396

Office Hours: Tuesday 10:00 am – 12:00 pm

OVERVIEW

The concept of “patient-centered medicine”—health care that embraces patients as complete

people—has gained prominence in many parts of the world. Why is how we think about

“patients” so important? What does it mean to provide “quality” medical care? What constitutes

a good health outcome or a bad one? How do people develop health conditions in the first place?

How do they experience these changes on a personal level? Health care requires just as much

attention to social factors as it does to clinical ones, yet researchers have only recently begun to

examine how these forces work together to produce or diminish well-being. “Medical

sociology”—the study of social causes and consequences of health—is an exciting and rapidly

growing discipline that is changing the way people think about health in multiple domains.

COURSE GOALS

This course will orient you to the field of medical sociology, and give you practice in using the

fundamental tools of the discipline. Specifically, it will help you develop basic knowledge about

key medical sociology topics, expose you to current research studies and findings, help you

understand how and when to apply specific sociomedical concepts and models, and encourage

you to think critically about course material. It will also help you synthesize concepts to think

creatively and strategically about central social issues in health and medicine. These include

patient-provider communication, social support, stigma management, medical ethics, health and

wellness measurement, social determinants of health, medical care delivery, paying for health

care, and health disparities. We will explore two broad questions: (1) How do social factors

cause different health states? (2) How does society respond to different health states?

COURSE OBJECTIVES

By the end of the semester, you should be able to:

Describe different types of health care organizations, insurance, and financing.

Differentiate individual, group, and institutional influences on health.

Articulate how elements of health and medicine are measured and tracked.

Explain why and how social inequality affects health, and vice versa.

Compare and contrast the attributes and challenges of different health care settings.

Summarize major concepts and theories on important medical sociology issues.

Find and interpret news coverage of current issues in medical sociology.

1

Apply sociological concepts and models to health, illness, and disability.

Write basic, brief critical responses to course readings.

Generalize your knowledge about medical sociology to other topics, where appropriate.

Approach learning new material strategically—in medical sociology and other areas.

I teach new concepts by relating them to what you already know, and by helping you organize

information into categories that make sense to you. I emphasize applying and challenging

knowledge so that you can participate actively in class meetings and take full advantage of your

unique strengths as a learner. As Mark Twain once said, “Never let your schooling interfere with

your education!”

REQUIRED READINGS

No textbook is required. All of the following pieces are posted on Blackboard.

Adler, Nancy E. and Joan M. Ostrove. 1999. “Socioeconomic Status and Health: What We

Know and What We Don’t.” Socioeconomic Status and Health in Industrial Nations: Social,

Psychological, and Biological Pathways 896:3-15.

Akers, Aletha Y., Melvin R. Muhammad, and Giselle Corbie-Smith. 2011. “‘When you got

nothing to do, you do somebody’: A community’s perceptions of neighborhood effects on

adolescent sexual behaviors.” Social Science & Medicine 72:91-99.

Burdette, Amy and Terrence Hill. 2008. “An examination of processes linking perceived

neighborhood disorder and obesity.” Social Science & Medicine 67:38-46.

Bury, Michael. 1991. “The Sociology of Chronic Illness: A Review of Research and

Prospects.” Sociology of Health & Illness 13:451−468.

Busfield, Joan. 2006. “Pills, Power, People: Sociological Understandings of the

Pharmaceutical Industry.” Sociology 40(2):297-314.

Butterfoss, Frances Dunn, Robert M. Goodman, and Abraham Wandersman. 1993.

“Community Coalitions for Prevention and Health Promotion.” Health Education Research

8(3):315-330.

Charmaz, Kathy. 2003. “Experiencing Chronic Illness.” Pp. 277−292 in Handbook of Social

Studies in Health & Medicine, edited by G. Albrecht, R. Fitzpatrick, and S. Scrimshaw.

Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Cockerham, William. 2007. Medical Sociology, 10th Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Pearson Prentice Hall.

Conrad, Peter and Valerie Leiter. 2004. “Medicalization, Markets, and Consumers.” Journal

of Health and Social Behavior 45 (Extra Issue):158-176.

Chrisler, Joan and Paula Caplan. 2002. “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde: How

PMS became a Cultural Phenomenon and Psychiatric Disorder.” Annual Review of Sex

Research 13:274-306.

Ferraro, Kenneth and Tatyana Pylypiv Shippee. 2009. “Aging and Cumulative Inequality:

How does Inequality get under the Skin?” The Gerontologist 49:333−343.

Freese, Jeremy. 2008. “Genetics and the Social Science Explanation of Individual

Outcomes.” American Journal of Sociology 114 Suppl.: S1–S35.

2

Freund, Peter, Meredith McGuire, and Linda Podhurst. 2003. Health, Illness, and the Social

Body: A Critical Sociology, 4th Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Iglehart, John. 2010. “The Political Fight Over Comparative Effectiveness Research.”

Health Affairs 29:1757-1760.

Institute of Medicine. 2001. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the

Quality Chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National

Academies Press.

Gawande, Atul. 2009. “The Cost Conundrum: What a Texas town can teach us about health

care.” The New Yorker 85(16):36-44.

Geronimus, Arline T., Margaret Hicken, Danya Keene, and John Bound. 2006.

“‘Weathering’ and Age-Patterns of Allostatic Load Scores among Blacks and Whites in the

United States.” American Journal of Public Health 96: 826-833.

Groopman, Jerome. 2007. “What’s the Trouble? How doctors think.” The New Yorker 29.

Hafferty, Frederich. 1988. “Cadaver Stories and the Emotional Socialization of Medical

Students.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 29:344-356.

Henderson, Gail et al. 2007. “Clinical Trials and Medical Care: Defining the Therapeutic

Misconception.” PLoS Med 4(11): e324.

Hummer, Robert. 1996. “Black-White Differences in Health and Mortality: A Review and

Conceptual Model.” The Sociological Quarterly 37:105−125.

Josefsson, Ulrika. 2005. “Coping with Illness Online: The Case of Patients’ Online

Communities. The Information Society: An International Journal 21(2):133-141.

Karp, David. 1996. “Illness and Identity.” Pp. 50-77 in Speaking of Sadness. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Link, Bruce G. and Jo Phelan. 2010. “Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Health

Inequalities.” Pp. 3−17 in Handbook of Medical Sociology, 6th Edition, edited by C. Bird, P.

Conrad, A. Fremont, and S. Timmermans. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Matcha, Duane. 2000. Medical Sociology. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Nowakowski, Alexandra C.H. 2010. “More Options for Treating Pain.” Hospitals & Health

Networks Weekly. 2 February 2010.

Pearlin, Leonard I. 1989. “The Sociological Study of Stress.” Journal of Health and Social

Behavior (1989):241-256.

Pescosolido, Bernice A., Steven A. Tuch, and Jack K. Martin. 2001. “The Profession of

Medicine and the Public: Examining Americans’ Changing Confidence in Physician

Authority from the Beginning of the ‘Health Care Crisis’ to the Era of Health Care Reform.”

Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42(1):1-16.

Rieker, Patricia, Chloe Bird, and Martha Lang. 2013. “Understanding Gender and Health:

Old Patterns, New Trends, and Future Directions.” Pp. 52−74 in Handbook of Medical

Sociology, 6th Edition, edited by C. Bird, P. Conrad, A. Fremont, and S. Timmermans.

Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Rier, David A. 2000. “The missing voice of the critically ill: a medical sociologist’s firstperson account.” Sociology of Health & Illness 22(1):68-93.

Rosenberg, Charles. 2002. “The Tyranny of Diagnosis: Specific Entities and Individual

Experience.” The Milbank Quarterly, 80:237-260.

3

Rosich, Katherine and Janet Hankin. 2010. “Executive Summary: What Do We Know? Key

Findings from 50 Years of Medical Sociology.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior,

Extra Issue, 51:S1-S9.

Ross, Catherine and John Mirowsky. 1989. “Psychiatric Diagnosis as Reified Measurement.”

Journal of Health and Social Behavior (1989):11-25.

Ross, Catherine and John Mirowsky. 2000. “Does Medical Insurance Contribute to

Socioeconomic Differentials in Health?” The Milbank Quarterly 78:291−321.

Shea, Christopher. 2000. “Don’t Talk to the Humans: The crackdown on social science

research.” Lingua Franca 10(6):26-34.

Smith, Allen and Sherryl Kleinman. 1989. “Managing Emotions in Medical School.” Social

Psychology Quarterly, 52:6-69.

Street, Debra, Stephanie Burge, Jill Quadagno, and Anne Barrett. 2007. “The Salience of

Social Relationships on Resident Wellbeing in Assisted Living.” Journal of Gerontology

62B (2):S129-134.

Taylor, John and R. Jay Turner. 2002. “Perceived Discrimination, Social Stress, and

Depression in the Transition to Adulthood: Racial Contrasts.” Social Psychology Quarterly

65:213-25.

Taylor, Miles G. 2008. “Timing, Accumulation, and the Black/White Disability Gap in Later

Life: A Test of Weathering.” Research on Aging: Special Issue on Race, SES, and Health 30:

226-250.

Thoits, Peggy A. “Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next?”

Journal of Health and Social Behavior (1995): 53-79.

Tiefer, Lenore. 2006. “The Viagra Phenomenon.” Sexualities 9:273-294.

Topo, Päivi and Sonja Iltanen-Tähkävuori. 2010. “Scripting Patienthood with Patient

Clothing.” Social Science and Medicine, 70:1682-9.

Ueno, Koji. 2010. “Mental Health Differences Between Young Adults With and Without

Same-Sex Contact: A Simultaneous Examination of Underlying Mechanisms.” Journal of

Health and Social Behavior 51(4):391-407.

Wallis, Anne Baber, Peter J. Winch, and Patricia J. O’Campo. 2010. “This Is Not a Well

Place: Neighborhood and Stress in Pigtown.” Health Care for Women International, 31:113130.

Williams, Robert L. and Kim Yanoshik. 2001. “Can You Do a Community Health

Assessment without Talking to the Community?” Journal of Community Health, 26(4):233247.

Woolhandler, Steffie, Terry Campbell, and David U. Himmelstein. 2003. “Costs of Health

Care Administration in the U.S. and Canada.” New England Journal of Medicine, 349:768775.

Zola, Irving Kenneth. 1991. “Bringing Our Bodies and Ourselves Back In: Reflections on a

Past, Present, and Future ‘Medical Sociology’.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior

32(1):1-16.

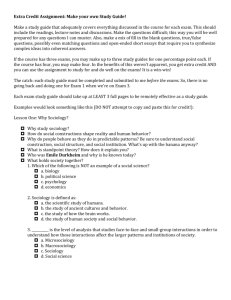

4 COURSE CONTENT AND OUTLINE

WEEK 1 (January 6 & January 8)

Getting oriented: introductions, course overview, syllabus review

Reading: Course syllabus (available on Blackboard)

Support for a sociology of health and medicine

Reading: Humberstone 2007

Reading: Rosich and Hankin 2010

*** Bring syllabus to class on first day! ***

WEEK 2 (January 13 & January 15)

Foundational concepts and terms

Reading: Cockerham 2007

Reading: Matcha 2000

Biomedical, biopsychosocial, and sociological health models

Reading: Freese 2008

Reading: Pearlin 1989

WEEK 3 (January 20 & January 22)

Social and organizational changes in medicine

Reading: Weiss 2009

Reading: Cockerham 2007

Assignment 1: Available on Blackboard, complete over next week

*** No class on January 20 (Martin Luther King Day) ***

WEEK 4 (January 27 & January 29)

Epidemiology: transitional patterns and social approaches

Reading: Freund, McGuire, and Podhurst 2003

Reading: Geronimus et al. 2006

Introduction to theories of health inequality

Reading: Link and Phelan 2010

Reading: Ferraro and Shippee 2009

*** Assignment 1 due by 11:59 pm on January 29 ***

WEEK 5 (February 3 & February 5)

Social patterning of health and illness

Reading: Adler and Ostrove 1999

Reading: Burdette and Hill 2008

Measures of health and functionality

Reading: Taylor 2008

Reading: Taylor and Turner 2002

5 WEEK 6 (February 10 & February 12)

Dynamics and causes of health inequality

Reading: Hummer 1996

Reading: Rieker, Bird, and Lang 2010

Strategies for mitigating health disparities

Reading: Ueno 2010

Reading: Akers, Muhummad, and Corbie-Smith 2011

Assignment 2: Available on Blackboard, complete over next week

WEEK 7 (February 17 & February 19)

People becoming patients and patients managing emotions

Reading: Charmaz 2003

Reading: Bury 1991

Coping: types and social resources

Reading: Josefsson 2005

Reading: Thoits 1995

*** Assignment 2 due by 11:59 pm on February 19 ***

NB: February 21 is the last day to drop a course without receiving a grade.

WEEK 8 (February 24 & February 26)

History of diagnosis and treatment

Reading: Weiss 2009

Reading: Rosenberg 2002

Experience of illness: navigating medical systems

Reading: Groopman 2007

Reading: Rier 2000

Exam I: Available on Blackboard, complete over next week

WEEK 9 (March 3 & March 5)

Biomedical models of illness: problems and alternatives

Reading: Conrad and Leiter 2004

Reading: Chrisler and Caplan 2002

Medicalization and its consequences

Reading: Zola 1991

Reading: Mirowsky and Ross 1989

*** Exam I due by 11:59 pm on March 5 ***

*** SPRING BREAK is the week of March 10! Get some rest! ***

6 WEEK 10 (March 17 & March 19)

The pharmaceutical industry

Reading: Tiefer 2006

Reading: Busfield 2006

Sociomedical research: ethics, review, and funding

Reading: Henderson et al. 2007

Reading: Shea 2000

*** Optional course evaluation survey due by 11:59 pm on March 19 ***

WEEK 11 (March 24 & March 26)

Health professions and physician socialization

Reading: Freund, McGuire, and Podhurst 2003

Reading: Hafferty 1988

People as “cases”: physician attitudes toward patients

Reading: Smith and Kleinman 1989

Reading: Topo and Iltanen-Tähkävuori 2010

Assignment 3: Available on Blackboard, complete over next week

WEEK 12 (March 31 & April 2)

Models of health care delivery

Reading: Karp 1996

Reading: Gawande 2009

Relationships between health services and health outcomes

Reading: Street et al. 2007

Reading: Ross and Mirowsky 2000

*** Assignment 3 due by 11:59 pm on April 2 Feb***

NB: April 4 is the deadline for late drop with dean’s permission.

WEEK 13 (April 7 & April 9)

US health care system: unique attributes

Reading: Woolhandler, Campbell, and Himmelstein 2003

Reading: Nowakowski 2010

Health care reform

Reading: Pescosolido, Tuch, and Martin 2001

Reading: Institute of Medicine 2001

Assignment 4: Available on Blackboard, complete over next week

WEEK 14 (April 14 & April 16)

Comparative effectiveness research

Reading: Iglehart 2010

Reading: Butterfoss, Goodman, and Wandersman 1993

Community health assessment

Reading: Williams and Yanoshik 2001

Reading: Wallis, Winch, and O’Campo 2010

*** Assignment 4 due by 11:59 pm on April 16 ***

7 WEEK 15 (April 21 & April 23)

Current events in medical sociology

Reading: Catch up on any readings you haven’t done yet!

Activity: Find one news article related to medical sociology!

Course wrap-up

Exam II: Available on Blackboard, complete over next week

SPOT Evaluations: Will go out over email at end of semester

FINAL EXAM

*** Exam II due by 11:59 pm on April 30 ***

COURSE REQUIREMENTS

Blackboard. You can find all of the course readings in the “Course Library” area on our

Blackboard site. Please let me know promptly if you have difficulty accessing any of the PDFs!

Submit your assignments and exams to Blackboard as requested—I will show everyone where to

find things early in the semester. Make sure you also check Blackboard regularly to keep up with

newly posted information and changes to the syllabus.

Attendance. I will circulate an attendance sheet during every class period. If I take attendance

and you are present for the entire class period and signed the sign in sheet I will give you an

attendance point for that day. Accumulated attendance points will count as extra credit toward

your final grade. You will need a valid written excuse (e.g., attending a conference, having

surgery) to get attendance points for any class you need to miss. If you have an emergency and

cannot attend class, please let me know ASAP (before class if possible) via e-mail, and give me

whatever written documentation you can provide at the next class meeting. Note that class

attendance and grades are very highly correlated, so come when you can!

Class participation. Engaging our brains in discussion of course materials enhances our

learning and makes the classroom experience much more fun. I keep my lecture slides general

and brief because I believe students should drive our journey in the classroom. If you have a

question or comment about what we are covering, signal that you would like to speak, and I will

call on you. To encourage you to engage actively, I give points for class participation. This does

not mean that you need to talk constantly to get full credit! Rather, I want to see evidence that

you are thinking critically about the different course modules and challenging yourself

intellectually. I also recognize that not every student feels equally comfortable speaking in front

of others. It is perfectly okay not to speak up frequently during lectures, but I do expect every

student to participate actively in smaller discussion activities.

Readings. Lectures will highlight and/or build on the readings so you should finish assigned

readings prior to coming to class. Being prepared for class will also enhance your learning

experience and allow you to participate! The instructions for writing response papers are a great

guide for active reading. Think about these topics as you read each article, and take a few notes!

I personally find it works very well to create a matrix with one column for the discussion topics

and another column for brief notes about each topic, but I encourage you to take notes in

whatever way you find most useful.

8 Examinations. There will be two exams, both of which are take-home and should be submitted

through Blackboard. These exams will consist of multiple choice items, with the goal of getting

you to demonstrate knowledge of key concepts and think critically about course materials. You

may use your notes and readings while completing the exams, but note that you will not be able

to complete the exams in the required time if you have not prepared in advance. I will give

extensions on exam deadlines only for emergencies or for extenuating circumstances. In such an

event, you must give me a valid written excuse that I can keep for my records. For more

information, please review Florida State University’s policy on final exams, which instructors

and students are mandated to follow: http://undergrad.fsu.edu/Retention/exam.html.

Assignments. You will complete four written assignments during the semester. For each of these

assignments, you will write a short (1 to 2 pages double-spaced) “response paper” to one of the

readings for that module. Each assignment will ask you to think critically about course readings

and form your own positions on the content.

Assignment 1: Health/illness models and social epidemiology

Assignment 2: Inequality, medicalization, and coping

Assignment 3: Pharma and health professions

Assignment 4: Health care delivery models and systems

You will have some choice in which readings you address in each assignment. You may use your

notes, book, and any other resources you find useful. I also strongly encourage you to discuss the

course readings with other students! However, you may not collaborate with other students to do

the actual writing—all work must be completely your own. I will discuss the details of these

assignments in class and will post them in advance on the Blackboard site. I will also post the

standards with which I grade these assignments, so you have a clear idea of how to approach the

work.

If you need to submit an assignment late, talk to me beforehand (except in the case of severe

emergencies, in which case you should talk to me as soon as possible). I reserve the right to

deduct points for late submissions. However, I also believe that grades should reflect learning

rather than ability to navigate bureaucracy. Consequently, the more important thing is to take

responsibility for letting me know if you will have a problem turning in an assignment on time,

and to work with me on alternative arrangements.

Course evaluation. I will use Blackboard to administer a course evaluation survey about

halfway through the semester. Since there is no better way for me to improve my teaching—and

thus, your experience in the course—than asking for your feedback, completing this evaluation

will boost your final course grade. You will receive a small amount of extra credit toward your

course grade by completing this evaluation. At the end of the term, you will complete the

mandatory SPOT assessment form for all FSU courses.

9 GRADING & EVALUATION

Final grades will be calculated according to the following formula:

ASSESSMENT

Assignment 1

Assignment 2

Exam I

Assignment 3

Assignment 4

Exam II

Class Participation

TOTAL

TOPICS COVERED

Health/illness models and social epidemiology

Inequality, medicalization, and coping

First half of semester only

Pharma and health professions

Health care delivery models and systems

Second half of semester only

Readings for each session

WEIGHT

15%

15%

10%

15%

15%

10%

20%

100%

I use full letter grades in this course. Cut-points for letter grades are: A = 90-100%; B = 80-89%;

C = 70-79%; D = 60-69%; F < 59%.

You will not receive formal letter grades for exams or assignments; I will add your points for all

exams and assignments to derive your final grade for the course. To help you keep tabs on your

own performance, however, I will compute percentage scores for each assessment and post these

to Blackboard. You can get a bit of extra credit by attending class regularly, and by completing

the optional course evaluation survey on Blackboard midway through the semester.

ACADEMIC HONOR POLICY

The Florida State University Academic Honor Policy outlines the University’s expectations for

the integrity of students’ academic work, the procedures for resolving alleged violations of those

expectations, and the rights and responsibilities of students and faculty members throughout the

process. Students are responsible for reading the Academic Honor Policy and for living up to

their pledge to “. . . be honest and truthful and . . . [to] strive for personal and institutional

integrity at Florida State University.” (Florida State University Academic Honor Policy, found at

http://fda.fsu.edu/Academics/Academic-Honor-Policy.)

CLASSROOM COURTESY

Basic classroom courtesy ensures that everyone has the opportunity to learn without distractions

in a physically and emotionally safe environment. So, please refrain from having “side

conversations”, answering cell phones in class, or otherwise disrupting class activities. On the

other hand, asking questions and participating in class discussion is strongly encouraged!

Likewise, you may use a laptop, tablet PC, and/or e-reader in class to assist you in learning and

taking notes—in fact, I encourage students to avoid printing out articles if at all possible. That

said, I reserve the right to take action if you repeatedly engage in distracting or disruptive

behavior with any technology you bring to class. If you must have a cell phone to receive

emergency calls about children or other loved ones, keep it on vibrate and step out of class to

answer. Please also make a general effort to minimize noise in the classroom—for example, if

you bring food to class, choose snacks that you can eat quietly.

10 Most importantly, respect your fellow students at all times. Hostile comments directed at other

students or population groups will not be tolerated. I refuse to censor anyone, but consider this

fair warning that if you disparage another student in any way, I will call you on it and give

everyone the opportunity to discuss the incident together. I have zero interest in embarrassing or

punishing anyone, so please think about the likely impact of your words before you speak.

EMAIL ETIQUETTE

In every email you send me, please include your first and last name, the course and the section

number or date/time of our class. Generally this course has upwards of 40 enrolled students, so

this is crucial to help me know who you are and how I can help you! Before asking questions

about basic course information, please check the course Blackboard site and the syllabus—be a

strategic learner! These skills will take you far in your future career, and in most cases, you will

get the information you need much more quickly by looking at the course website instead of emailing me.

AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT

Students with disabilities needing academic accommodation should: (1) register with and

provide documentation to the Student Disability Resource Center; and (2) bring a letter to the

instructor indicating the need for accommodation and what type. This should be done during the

first week of class. This syllabus and other class materials are available in alternative format

upon request. For more information about services available to FSU students with disabilities,

contact the:

Student Disability Resource Center

874 Traditions Way

108 Student Services Building

Florida State University

Tallahassee, FL 32306-4167

(850) 644-9566 (voice)

(850) 644-8504 (TDD)

sdrc@admin.fsu.edu

http://www.disabilitycenter.fsu.edu/

FREE TUTORING SERVICES

On-campus tutoring and writing assistance is available for many courses at Florida State

University. For more information, visit the Academic Center for Excellence (ACE) Tutoring

Services’ comprehensive list of on-campus tutoring options: see http://ace.fsu.edu/tutoring or

contact tutor@fsu.edu. High-quality tutoring is available by appointment and on a walk-in basis.

These services are offered by tutors trained to encourage the highest level of individual academic

success while upholding personal academic integrity.

11 EXCUSED ABSENCES

Excused absences include documented illness, deaths in the family and other documented crises,

call to active military duty or jury duty, religious holy days, and official University activities.

These absences will be accommodated in a way that does not arbitrarily penalize students who

have a valid excuse. Consideration will also be given to students whose dependent children

experience serious illness.

INCOMPLETE GRADES

Missing work or completing assignments partially are insufficient reasons for a grade of

Incomplete. An Incomplete grade will not be given except under extenuating circumstances at

the instructor’s discretion. Note that College of Social Science guidelines require that students

seeking an “I” must have completed a substantial portion of the course and be passing the course.

If for any reason you do qualify for an Incomplete in this course, I will work with you to develop

a plan for completing your remaining work.

SYLLABUS CHANGE POLICY

This syllabus is a guide for the course and is subject to change—with advance notice, of course!

Class topics, assignments, reading selections, and scheduling may be modified by the instructor

as circumstances dictate. I will announce any necessary changes via email and in class.

12