Drunk Driving: Outline of a Public Information and Education Program

advertisement

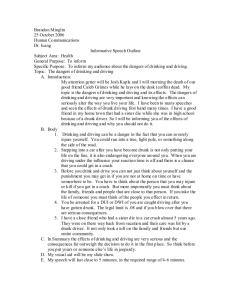

Drunk Driving: Outline of a Public Information and Education Program Dwight Fee1 For the past three years the Department of Transportation has been engaged in an extensive, nationwide public information and education program on the subject of drunk driving. This program has included research into public knowledge and attitudes on various alcohol safety issues; cooperative public education programs with govern­ mental and private organizations; plus 35 independent public education programs conducted by local Alcohol Safety Action Projects. Meanwhile, a study of the use of mass media for highway safety required by the Congress has been completed. Rather than attempting to discuss any single aspect of the program in depth, this paper reports on the status of the total program. It describes the activities and interests of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) in public education on this topic, indicates some of the public opinion survey research which is underway, and suggests a few priorities and plans for the future in hopes that we might discover mutual goals for collaboration. THE MESSAGE Perhaps the best way to describe the mass media program is to describe the materials developed to date for what we have called the Four Waves. The assumptions and objectives which underlie them will be made plain. The basic premise of the entire Alcohol Countermeasures Program is that it is the excessive, abusive use of alcohol among a relatively small segment of drivers that causes most alcohol-related fatalities, rather than normal, moderate use. In 1971 this was a unique definition of the drunk driving problem. A national survey at the time showed that more than half of our citizens believed to the contrary: that is, they believed that the worst culprits in alcohol crashes were the great mass of social drinkers. Thus, we had the job of a) convincing the public, key officials and professionals of a new definition of the problem; b) of motivating them to take new and different kinds of actions to identify, control and treat the problem drinker-driver; and c) of raising new hope that something could be done about this age-old problem. Therefore, in the First Wave of creative materials the focus was on these problem 1 U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. 789 790 D. Fee awareness issues. In print there were four magazine and newspaper advertisements, each in a variety of sizes. The headlines indicate the theme: TODAY YOUR FRIENDLY NEIGHBOR MAY KILL YOU . . . BY THE TIME YOU FINISH THIS MAGAZINE A DRUNK DRIVER WILL HAVE KILLED SOME­ ONE . . . HIS DRINKING PROBLEM IS NOTHING COMPARED TO HIS DRIVING PROBLEM . . . ONE OUT OF EVERY FIFTY CARS ON THE ROAD IS DRIVEN BY A DRUNK DRIVER. One particular ad mentions the guy next door who may have a drinking prob­ lem, pointing out that no matter how nice he is, if he drives when he is drunk, he is a potential killer. It goes on to say that problem drinkers killed 19,000 people in car accidents in the previous year, and explains the nature of the heavy drinking — for example, eight drinks in two hours — that characterizes the problem drinker-driver. The advertisement then goes on to mention the countermeasures necessary to “get the problem drinker off the road. For his sake. And yours.” The campaign was introduced in the 100 largest markets in the United States. A variety of material was distributed over the radio. On television, actor Dana Andrews presented a straightforward exposition of the scope of the problem and the means toward its control. The Second Wave of the program tried to personalize the problem by depicting the consequences of drunk driving and to continue to portray the problem drinking, which is involved in most alcohol related deaths on the highway. Some of the ads were created for specialty books and men’s magazines. The headlines continue to drive home the point: A DRINKING PROBLEM COULD KILL HIM . . . A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A RISING YOUNG PROBLEM DRINKER .. . THE WORLD’S MOST EXPENSIVE OPTION: LAST YEAR COST 19.000 LIVES. Another ad describing the ‘rising young problem drinker’ introduced a new appeal. It concludes, “If you know someone who’s killing himself with alcohol —but hasn’t yet killed anyone with a car — sit him down. Get into his head. Talk with his doctor, clergyman, whoever he’s close to.” It also included a plug for supporting official countermeasures. A high priority for NHTSA is the problem of youngsters being overly involved in fatal crashes. A special campaign was aimed at the young to warn them that about 8.000 persons under 25 are killed in alcohol-related crashes, usually at the hands of a driver who is also under 25. The number one killer of young Americans is truly — young Americans. Figure 1 is a sample of one of the ads most popular with campus editors. We are quite proud of the 19 major awards given these advertising materials during 1973. When people responded to these ads by writing to us, they were sent pamphlets outlining the scope and nature of the problem and the countermeasures, along with information on the relation of blood alcohol level and crash risk. The main purpose of the pamphlets, however, was for distribution at the local level where countermeasure programs were being organized. As mentioned above, a great deal of persuasion was aimed at professional and official groups whose practices and priorities we were trying to change. Ads were prepared for their publications. For law enforcement officers our aim was to encourage them to give higher priority to alcohol in traffic and to make them a part of a community-wide effort to identify problem drinker-drivers. The ad they received pointed out that, in an average Public Information and Education 791 I WASIN LOVE WITH AGIRL NAMEDCATHY. I KILLED HER. "It was last summer, and I was 18. Cathy was 18 too. It was the happiest summ er of my life. 1 had never been that happy before. 1 haven't been that happy since. And 1know I'll never be that happy again. It was warm and beautiful and so we bought a few bottles of wine and drove to the country to celebrate the Figure 1 night. We drank the wine and looked killing young people are most often at the stars and held each other and other young people. laughed. It must have been the stars and the wine and the warm wind. DRUNK DRIVER, DEPT. Y* BOX 1969 Nobody else was on the road.The D.C. 20013 top was down, and we were singing WASHINGTON, I don’t want to get killed and 1 don't and I didn’t even see the tree until want to kill anyone. Tell me how I can help* Youths Highway Safety I hit it.” Advisory Committee. Every year 8,000 American My name is.________________________ people between the ages of 15 and Address_________________________ City___________ State_____ Zip___ 25 are killed in alcohol related crashes. That’s more than combat. STOP DRIVING DRUNK. More than drugs. More than suicid( STOP KHUNG EACH O THER.^ ^ More than cancer. The people on this page are not real. But what happened to them is very real. The automobile crash is the num ber one cause of death of people your age. And the ironic thing is that the drunk drivers responsible for Example o f an advertisement. year, there are 18,000 murders committed in the United States —compared to 27,000 alcohol-related traffic deaths. We wanted the judges and attorneys to cooperate in using presentence investiga­ tion and legal resources to identify and deal effectively with alcohol-dependent people. Our aim with physicians was to have them deal with driving issues when they encountered problem drinkers among their patients. There were brochures to spell out details of specific countermeasure activity for th£key professions and official groups, that is, for the courts, doctors and police. Having an understanding of the problem and being willing to support official action to combat it, is not enough. What else can the individual do? Some new objectives emerged for the Third Wave of the advertising which began in the Fall of 1973. The basic objective of phase III advertising was to stimulate individuals to raise the issue of excessive drinking and driving as a social, peer group concern. It was to make excessive drinking and driving an explicit social concern for people where they live. In this wave we wanted to help the citizen raise this issue, to get it out into the open so that it could not be deliberately or inadvertently ignored. We aimed at getting Americans to see the responsibility and opportunity for every citizen to become involved in the prevention of drunk driving. We hoped to achieve this by stimulating discussions among individuals in their peer groups so that the topic could be treated with appropriate maturity and concern. 792 D. Fee The second objective of phase III was to describe specific steps or actions which individuals can take to reduce intoxication and to prevent excessive drinkers from driving. These may range from the role of the hostess in preventing excessive drinking to methods for persuading someone to give up his car keys and accept a ride home. Third, we continued to seek support of countermeasure programs and to encour­ age citizens to obtain implementation of these programs in their communities. The fourth objective, educating young drivers about the issues involved with alcohol and highway safety, was of high priority. The new campaign in Third Wave calls for personal and decisive action. The theme has become: “When a problem drinker drives it’s your problem.” Here is a sample ad: “When would you rather deal with a problem drinker . . . at the party, or after the party?” This particular ad in the series was also an award winner. It reads in part: He killed himself. He didn’t mean to. But he had lost control o f his drinking. And after the party, he lost control o f his driving and killed himself. Now his friends shake their heads and stare at the ground and wonder why. But the sad fact is his friends weren’t his friends. His friends let him die. The ad concludes: I f you are really his friend, don’t help him drink. I f he has been drink­ ing, don’t let him drive. Drive him yourself. Call a cab. Take his car keys. Everything you think you can’t do, you must do. The radio materials, again in a variety of styles, also raise the issue of personal responsibility. Two television commercials in this wave depict situations where signifi­ cant others have responsibilities for preventing drunk driving by people close to them. The current Fourth Wave of materials moves to specific calls for action. They seek to create social sanctions for the kinds of behaviours we are seeking to stimulate. Small gestures such as ‘calling a cab’, ‘paying for the taxi’, and ‘driving him yourself are the kinds of personal steps we want to foster. Another ad points out to both sexes that when a man and woman go out together, there is no rule that says the man has to drive. There are similar versions for youth publications. However, we refer to ‘friends who have had too much to drink’, instead of ‘problem drinkers’. In addition, there is a brochure offering suggestions for responsible hosting. It describes steps to take before the party and after the party, if it comes to that, to prevent a friend from driving under the influence. The ‘friends’ theme is carried over to radio announcements and television spots. Through these successive waves of creative materials the development of the strategies and appeals can be seen. THE MEDIA AND THE PUBLIC A vigorous effort has gone into the placement of these materials in public service space. These figures on placement are based on careful sampling of the media and take into account the fact that most of the placement has not occurred in prime time. By the second year the campaign achieved 23V6 billion adult impressions and received 32 million dollars worth of exposure. Public Information and Education 793 The media have cooperated very well in returning questionnaires indicating use of the materials, including the time at which the spots appeared, to yield these esti­ mates for print, radio and television. Table I lists the amounts of money spent on advertising by some of the leading advertisers of commercial products. The 32 million dollars for the alcohol safety campaign fits in just behind the leading beer advertiser but ahead of United Air Lines. TABLE I Leading Advertisers in 1973 by Category Advertiser Proctor and Gamble Sears and Roebuck General Foods General Motors Heublein Coca-Cola Goodyear Tire and Rubber Anheiseur Busch United Airlines Exxon Wrigley $ million 310.0 215.0 180.0 158.4 77.8 76.0 72.6 36.5 28.8 28.2 28.1 (Source: Ad Age) Public support for countermeasures has grown. In 1970, only about 58 per cent of the respondents in our survey were willing to pay more taxes to support “a program that would reduce alcohol-related traffic accidents by as much as a third or half’. Today, we find that 85 per cent of those interviewed agreed that people should support strict law enforcement to reduce the drunk driving problem, even if it means higher taxes. To test the effects of the campaign on personal responsibility, we added two questions to national surveys being conducted for the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) by Lou Harris in 1973. We asked people whether they had discussed the topic of drinking and driving in the past month and then asked, “During the past month have you or others that you know tried to prevent someone who had been drinking from driving an auto?” During the period the proportion of those who discussed the topic rose from 26% to 32%. Those who tried to prevent someone from driving rose from 16% to 21%. Interestingly, those more aware of alcohol advertising were more likely to have taken positive action. While these results are encouraging they also indicate a need for continuing public education, and we do not regard this single poll as sufficient to evaluate the effectiveness of the advertising program. Current plans call for copy testing of all television advertising this year and for tracking research on the overall campaign throughout the year. In the meantime, we are seeking to refine our public education goals and activities regarding the specific actions we can realistically ask Americans to take, regarding the control of drinking and of drunks when driving is going to occur. 794 D. Fee PRESENT RESEARCH Although all the results are not in, I will outline in brief the strategic research effort we have been engaged in. The objectives of the research are to define appropriate target audiences in terms of (a) the size of the groups; (b) their attitudes toward drunk driving and problem drinkers; (c) the situations in which they encounter drunk drivers; and (d) their willing­ ness to help: types of action they are willing to take to stop drunk drivers from driving. The main phase of the study consisted of 1,660 personal interviews averaging about 75 minutes each and conducted among a national probability sample of adults between the ages of 18 and 55 with the aim of analyzing adult and youth audiences. Som e Preliminary Results The purpose of the interview was totally unknown to the respondents when they were asked to rate the importance of various national problems. It is interesting to note that “Drunk Driving” ranked fifth in terms of the number of people (76%) who felt it was an “Extremely or Very Important” problem. This placed it ahead of such issues as Pollution of the Environment, the Energy Crisis and Unemployment (Figure 2). SOCIAL ISSUES: C O R R U P T IO N IN G O V E R N M E N T DRUG ABUSE C R IM E IN THE S T R E E T S D R U N K D R IV IN G P O L L U T IO N O F T H E E N V IR O N M E N T 67 A L C O H O L IS M 65 E N E R G Y C R IS IS U NEM PLO YM ENT R A C IA L C O N F L IC T S Figure 2 50 Percentage o f the'sample rating drunk driving and other social issues as “extremely ” or “very ” important (N = 1660). We found that 69 per cent of the persons interviewed had been in a social or business situation where alcoholic beverages were served over the past 3 months. We call these Alcohol Related Situations (ARS). This was reduced to 54 per cent when a frequency of at least once a month was considered (Table II). Eighty per cent of the locations of these ARS proved to be outside the individu­ al’s own home (Table III). The admission that drinking actually took place in a car in Public Information and Education 795 TABLE II The Frequency with which Respondents found themselves in a Social or Business Situation where Alcoholic Beverages were Served (N=l660) Alcohol related situations in past 3 months Respondents in situation Respondents not in situation Frequency in alcohol related situations in past 3 months Daily 5-6 times a week 2-4 times a week Once a week Once every 2 weeks Once every 3 weeks Once a month Once every 2 months Less than once every 2 months Not in situation % 69 31 3 \ 2 10 1 1 8 5 1 1 15 > 54 11 / 5 10 31 one per cent of the cases confirmed something that was indicated in our qualitative group sessions, which preceded the survey. TABLE III Locations at which Respondents found themselves in an Alcohol Related Situation (N=1145) Location % Social occasion in own home Friend’s/Relative’s home Bar, restaurant where meal was primary reason for attending Bar, restaurant where meal was not primary reason for attending Recreational event In a car 20 43 15 15 6 1 When we compared the involved individuals (those in ARS once a month or more) to the balance of the sample, some interesting differences in the demographic profile were observed. More of the Involved Group tended to come from households where the overall income was over $20,000 a year and where the head had college experience and was in a professional or managerial occupation. The individuals them­ selves were more often men, under 35, and from the North East and North Central Regions (Figure 3). 796 D. Fee E D U C A T IO N OF H E A D OF H O U S E H O L D OCCUPATION OF HEAD OF HOUSEHOLD U N D E R $ 1 0 ,0 0 0 $ 1 0 ,0 0 0 -5 1 4 .9 9 9 $ 1 5 , 0 0 0 - $ 1 9 .9 9 9 $ 2 0 ,0 0 0 A N O O V E R A G E OF R E SP O N D E N T U N O ER 2 5 Y E A R S O LD NOR TH C EN T R AL 45 Figure 3 ANO O VER A demographic comparison between persons involved in ARS once a month or more (N = 896) and those involved less than once a month (N = 764). M O S T L IK E L Y O U T C O M E : H O M E S A F E L Y W IT H O U T IN C ID E N T IN V O L V E M E N T W ITH TH E P O L IC E (Frorn Warning to Conviction/Punishment) A C C ID E N T , R E S U L T IN G IN P R O P E R T Y D A M A G E , IN J U R Y O R D E A T H W H E N D .W .I. D R IV E R IS: Figure 4 An Average Social D rin k e r A Teenager A Problem D rin ker Distribution o f ratings on “most likely outcom e” for 3 groups o f DWI drivers (N 1660). Public Information and Education 797 Our survey contained a question asking what was seen as the most likely out­ come when persons from the following groups drive: a) drunken Problem Drinkers, b) drunken Teenagers, and c) drunken Average Social Drinkers. Only about 25% of the Involved respondents felt the Teenager and the Problem Drinker could get home safely without incident and 30 per cent or more in each case foresaw an accident (Figure 4). The Social Drinker, on the other hand, was seen as getting home safely by 50 per cent and only 11 per cent predicted an accident. In other words more than three times as many respondents felt an intoxicated problem drinker would be more likely to have a serious accident than an average social drinker who is driving while intoxicated. A main reason for undertaking the study was to evaluate the measures people who are involved in ARS might take when dealing with excessive drinkers. To do this we factor analyzed the scores of 60 possible countermeasures and countermeasure situations. The result was to reduce the list to a manageable 21 unique actions. Of these, 3 have high potential for action and 10 a moderate potential (Table IV). The main study will deal with the full range of actions and alternatives for approaching them. TABLE IV Countermeasures People Involved in ARS might take toward Excessive Drinkers HIGH LIKELIHOOD POTENTIAL FOR ACTION: Offer to drive home a close friend or relative Invite a close friend or relative to stay over Plan to serve food at a party with the drinks to reduce the effects of alcohol MODERATE LIKELIHOOD POTENTIAL FOR ACTION: Call a taxi for a person who drank too much Treat seriously any conversation on drinking and driving, particularly when people are treating it lightly As a host/hostess, refuse to serve more drinks to a guest who is becoming intoxicated Take the keys away or restrain a close friend or relative Offer to drive a casual acquaintance or someone you just met from your own or a friend’s home Attend or host a party where no alcoholic beverages are served Report to authorities stores or bars that sell alcoholic beverages to minors Plan a party where drinking is cut off at a certain hour and replaced with non-alcoholic beverages and food As a host/hostess, plan for sober transportation or a place to stay for party guests In a bar, offer to drive home a casual acquaintance or someone you just met 798 D. Fee CONCLUSION In conclusion I would like to mention future priorities for this program: The first is to document the effects, wherever possible, of our public education programs at the national level. This has been made a priority for ASAP public educa­ tion programs as they develop objectives and programs designed to impact specific target audiences. Funds have been made available for continuation of many of the ASAPs and selection of these projects will in part depend upon their ability and willingness to undertake such measured programs. The second is to give support and to upgrade the capability of States and communities for the purpose of conducting professional communication programs. This involves long term, planned programs using research to establish needs and pro­ vide feedback on effectiveness. We plan to offer training seminars and on-site assis­ tance to State agencies engaged in public education activities. The third priority, is the coordination of our activities with governmental, pri­ vate and voluntary organizations nationally and internationally. Just a few preliminary findings from this study concerning the means for preven­ tion of drunken driving through the modifications of the behaviour of ‘by-standers’ have been outlined here. Not all aspects of this alcohol safety public education effort, the ASAP programs nor the mass media study have been discussed. More detailed reports can be obtained from our office in Washington.