Creating New Value for Interpreter Education Programs 2010

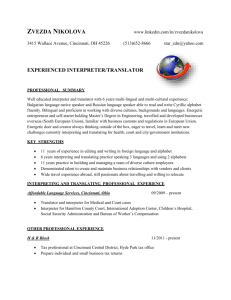

advertisement