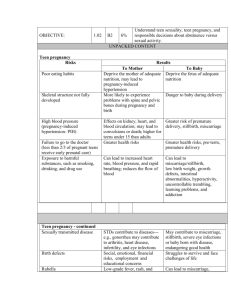

Teen Pregnancy Prevention pdf

advertisement