14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.072302.114200

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003. 65:103–31

doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.072302.114200

c 2003 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

Copyright °

First published online as a Review in Advance on December 9, 2002

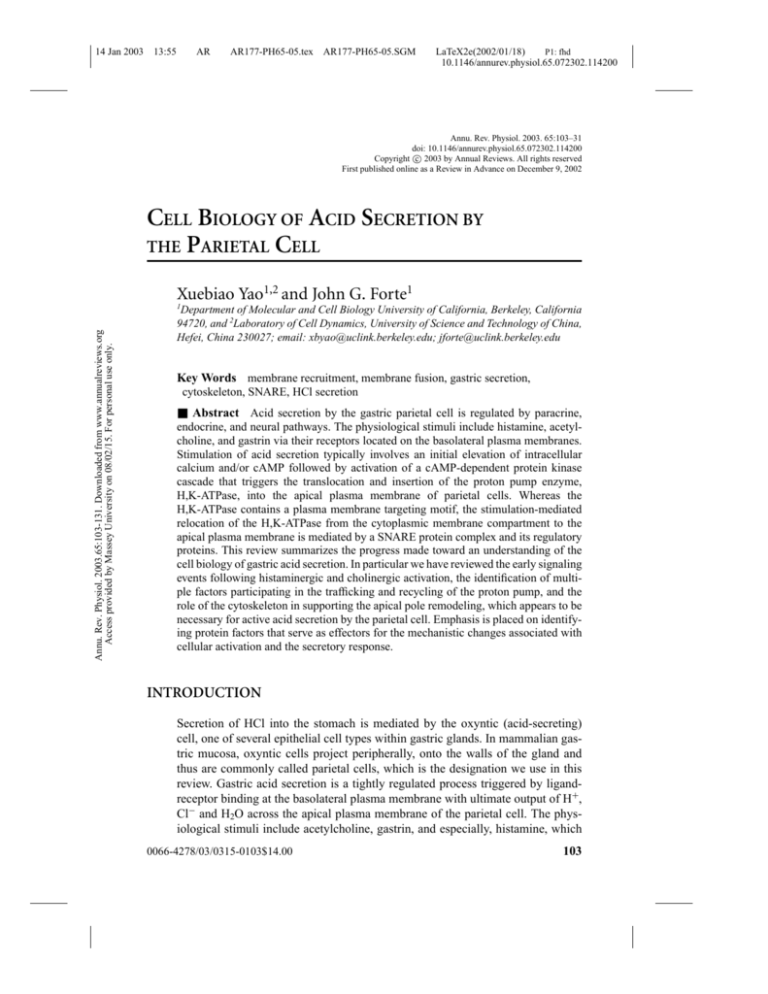

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION BY

THE PARIETAL CELL

Xuebiao Yao1,2 and John G. Forte1

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

1

Department of Molecular and Cell Biology University of California, Berkeley, California

94720, and 2Laboratory of Cell Dynamics, University of Science and Technology of China,

Hefei, China 230027; email: xbyao@uclink.berkeley.edu; jforte@uclink.berkeley.edu

Key Words membrane recruitment, membrane fusion, gastric secretion,

cytoskeleton, SNARE, HCl secretion

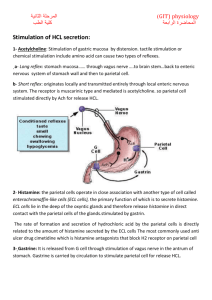

■ Abstract Acid secretion by the gastric parietal cell is regulated by paracrine,

endocrine, and neural pathways. The physiological stimuli include histamine, acetylcholine, and gastrin via their receptors located on the basolateral plasma membranes.

Stimulation of acid secretion typically involves an initial elevation of intracellular

calcium and/or cAMP followed by activation of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase

cascade that triggers the translocation and insertion of the proton pump enzyme,

H,K-ATPase, into the apical plasma membrane of parietal cells. Whereas the

H,K-ATPase contains a plasma membrane targeting motif, the stimulation-mediated

relocation of the H,K-ATPase from the cytoplasmic membrane compartment to the

apical plasma membrane is mediated by a SNARE protein complex and its regulatory

proteins. This review summarizes the progress made toward an understanding of the

cell biology of gastric acid secretion. In particular we have reviewed the early signaling

events following histaminergic and cholinergic activation, the identification of multiple factors participating in the trafficking and recycling of the proton pump, and the

role of the cytoskeleton in supporting the apical pole remodeling, which appears to be

necessary for active acid secretion by the parietal cell. Emphasis is placed on identifying protein factors that serve as effectors for the mechanistic changes associated with

cellular activation and the secretory response.

INTRODUCTION

Secretion of HCl into the stomach is mediated by the oxyntic (acid-secreting)

cell, one of several epithelial cell types within gastric glands. In mammalian gastric mucosa, oxyntic cells project peripherally, onto the walls of the gland and

thus are commonly called parietal cells, which is the designation we use in this

review. Gastric acid secretion is a tightly regulated process triggered by ligandreceptor binding at the basolateral plasma membrane with ultimate output of H+,

Cl− and H2O across the apical plasma membrane of the parietal cell. The physiological stimuli include acetylcholine, gastrin, and especially, histamine, which

0066-4278/03/0315-0103$14.00

103

14 Jan 2003

13:55

104

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

operate via basolateral membrane receptors. Stimulation of acid secretion typically

involves an initial elevation of intracellular calcium and cAMP, followed by activation of protein kinase cascades, which trigger the translocation and insertion of

H,K-ATPase—the proton pump enzyme—into the apical plasma membrane of the

parietal cell. This review primarily focuses on research over the past 10 years that

has sought to identify and describe specific roles for proteins involved in the activation, membrane translocation, and recycling processes that underlie acid secretion.

Table 1 provides a summary of the various proteins that have been implicated in the

functional activity of parietal cell secretion. In the course of this review, relevant

earlier studies are briefly discussed and references given to related review articles.

AN ELABORATE STRUCTURAL BASIS

FOR ACID SECRETION

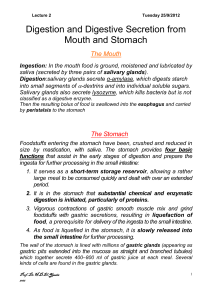

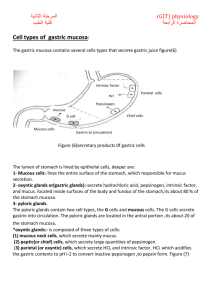

The parietal cell is a highly specialized epithelial cell with several distinctive

morphological characteristics that directly bear on its functional activities (1).

The apical plasma membrane has the unusual structural form of a series of small

canals (canaliculi) that invaginate from the surface and project throughout the

entire cell interior, with frequent interconnections among canaliculi. In the nonsecreting or resting parietal cell, these apical canalicular surfaces are lined with

short, stubby microvilli that are supported by prominent actin microfilaments including accessory actin-binding proteins. Throughout the cytoplasmic space there

is an abundance of membranous structures, rich in H,K-ATPase, that take the morphological form of vesicles, tubules, and cisternal sacs; these are commonly called

H,K-ATPase-rich tubulovesicles.

Parietal cells undergo a profound morphological transition upon activation of

acid secretion. Although limited by the optics of light microscopy, careful histological examination by Golgi in the late 19th century noted the enlargement of

canaliculi that occurred in secreting parietal cells. Electron micrographs of maximally stimulated cells have since revealed dilated canalicular spaces, a dramatically

expanded apical membrane surface with elongated microvilli, and diminution of

cytoplasmic tubulovesicles (2–4). Mounting evidence has contributed to a general

consensus for the membrane recycling hypothesis which holds that activation of

acid secretion results in a fusion-based recruitment of H,K-ATPase-rich cytoplasmic membranes into the apical plasma membrane (5). However, an alternate view

has argued that the H,K-ATPase-rich membranes are contiguous with the apical

plasma membrane in both resting and stimulated states, thus negating the need

for a fusion-based recruitment process (6–8). Recent evidence has clarified the

morphological argument through the use of high-pressure, rapid-freeze fixation to

prepare gastric parietal cells for electron microscopy (EM) and analysis of threedimensional structure (9). Models constructed from ultra-thin serial sections, as

well as tomographic reconstruction of thick tissue sections using high voltage EM,

clearly demonstrate the separation of tubulovesicular membranes from the plasma

14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

105

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

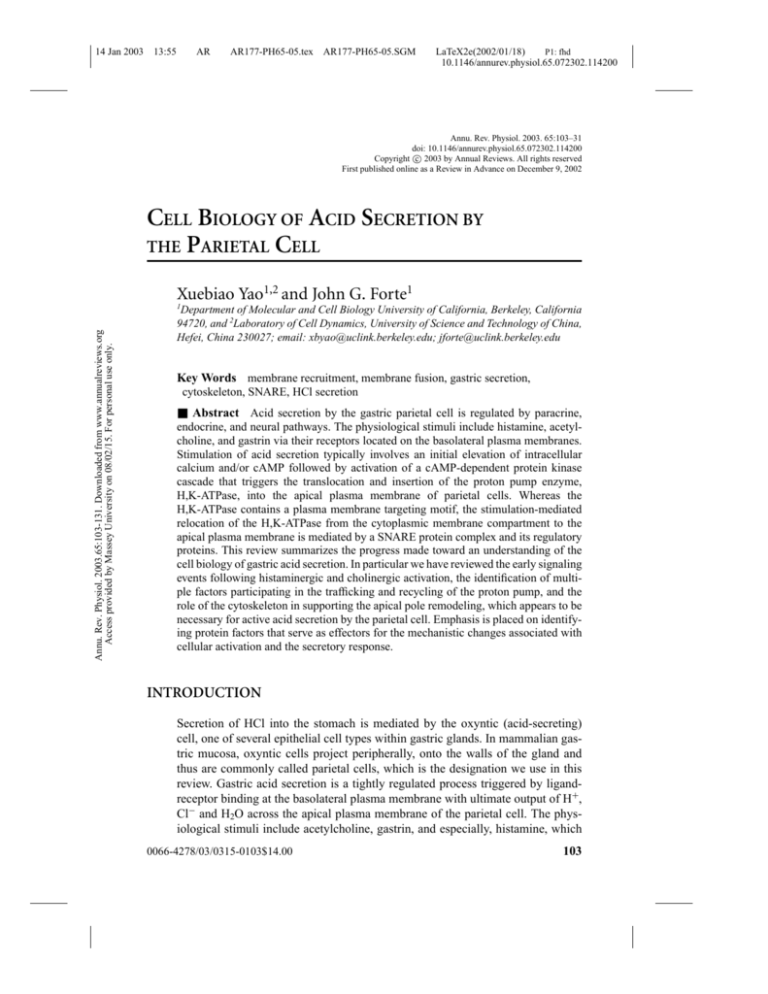

TABLE 1 Summary of parietal cell proteins implicated in the cell activation process

Name

Mass

(kDa)

Cellular

location

Presumed

function

Reference

Proton pump

H,K-ATPase

α-, β-subunits

α = 96

β = 60–80

Tubulovesicle (resting)

Apical PM (secreting)

H+ pumping

stabilize α-subunit

(86)

(115)

Apical PM (?)

Cytoplasm (resting)

Apical PM (secreting)

Apical PM

Cytoplasm (resting)

Apical PM (secreting)

Cytoplasm (resting)

Apical PM (secreting)

?

Tubulovesicle (resting)

Docking protein

H,K-ATPase translocation

(92, 93)

(92, 94)

(94)

(92)

(92, 93)

H,K-ATPase translocation

Rab11-myosin Vb binding

(94, 101)

(94, 101)

(100)

(103)

75

37

160; 35

Tubulovesicle (resting)

Tubulovesicle (resting)

Apical PM, tubulovesicles

Rab11 binding

Vesicle trafficking

Endocytosis

(103)

(93)

(104, 105)

110

Apical PM

Tubulovesicle (resting)

Endocytosis

Endocytosis

(105)

(104, 105)

cat. = 43

reg. = 52

80

cat. = 110

reg. = 85

50

34

110

Cytoplasm

Basolateral PM

Cytosol; membranes

?

Activation

Anchoring

Protein phosphorylation

PI phosphorylation

(17)

Cytosol

Cytosol

Cytosol

Protein phosphorylation

Protein phosphorylation

Myosin lc phosphorylation

(54)

(59, 60)

(146)

43

43

55

80

Apical microvilli

Basolateral PM

Cytoplasm

Apical microvilli

(134)

(134)

(150)

(22, 24)

Coroninse

66

Apical microvilli

Myosin V

Lasp-1

110

28

Endosome

Apical PM

Ankyrin

110

Apical PM

Spectrin

220/240

Apical PM

Microvillar formation

Polarity formation (?)

TV trafficking ?

PKA-regulated membraneactin-filament linker

PKC-dependent membraneactin linker

Rab11a-binding; recycling

Membrane-cytoskeleton

linking protein

H,K-ATPase binding

linking protein

Membrane-cytoskeleton

120

cat. = 80

reg. = 30

65

?

Cytosol

PKA anchoring

Hydrolysis of ezrin

(146)

(147)

Cytosol (resting)

PM (stimulated)

Cl− channel regulation

(26, 42)

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

Trafficking and membrane recycling proteins

Syntaxin 1

34

Syntaxin 3

34

SNAP-25

VAMP-2

25

18

Rab11

23

Rab25

Rab11-interacting

proteins (FIP1 and FIP2)

pp75/Rip11

SCAMPs

Clathrin (heavy and

light chains)

Dynamin

α-, β-, γ -adaptins

23

Regulatory kinases

PKA

PKC (multiple isozymes)

PI3 kinase

CAM kinase

MAP kinase

MLCK

Cytoskeleton

Actin

β-cytoplasmic

γ -cytoplasmic

Tubulins

Ezrin

Other proteins

AKAP120

Calpain I

Parchorin

PM = plasma membrane; TV = tubulovesicles.

SNARE pairing

H,K-ATPase translocation

H,K-ATPase translocation

(52, 53)

(28)

(113)

(39, 41)

(125)

(125)

14 Jan 2003

13:55

106

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

membrane and generally confirm early studies using chemical fixation techniques.

This revisiting of parietal cell ultrastructure, together with the requirement for

recruitment/fusion-based proteins in parietal cell activation (see below) reinforces

the recruitment-recycling model of parietal cell activation. In addition, this new

fixation method has revealed that the abundant parietal cell mitochondria form an

extensive reticular network throughout the cytoplasm, as has been reported for

several other cell types. Because of the close coupling between acid secretion and

oxidative metabolism, it will be of interest to evaluate whether, and to what extent,

dynamics of mitochondria are related to the cell activation.

SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION UNDERLYING GASTRIC

ACID SECRETION

Activation of acid secretion by parietal cells is triggered by paracrine, endocrine,

and neural stimuli in vivo. Study of the cell biology of acid secretion has been

greatly facilitated by the technique of gastric gland isolation, developed by

Berglindh & Öbrink, along with the method to monitor acid secretion in vitro

by accumulation of the weak base, aminopyrine (10).

From the pioneering work of Chew and her colleagues (11, 12), primary cultures of parietal cells have also been of special value in localizing functionally

relevant proteins and defining events in the secretory cascade. Many intracellular

signaling pathways have now been identified with their contributing roles in parietal cell activation, including protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC),

Ca2+-calmodulin (CaM) kinase II, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3 kinase), and

several other downstream kinases. Histaminergic stimulation is by far the most

potent activation pathway observed for the stimulation of gastric acid secretion

in vitro. Although cholinergic and gastrinergic stimulation can be seen in vitro,

the magnitude of stimulation for many species is much reduced compared with

stimulation in vivo, most likely because parietal cells are in close contact with

histamine-releasing enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells in vivo (13). Isolated canine parietal cells appear to be an exception, tending to be more responsive to

cholinergic stimuli than to histamine (1). In this review we first focus on signaling

events underlying cAMP-mediated stimulation and the PKA stimulation pathway,

and then move to a discussion of cholinergic pathways and an overview of other

kinase pathways.

cAMP-Mediated PKA Activation and Protein Phosphorylation

Evidence implicating cAMP as an intracellular messenger mediating HCl secretion was presented by Roth & Ivy more than 50 years ago (14). Using isolated

gastric glands, Chew et al. (15) directly showed that histamine elevates intracellular levels of cAMP leading to activation of PKA (16), and specifically type I

cAMP-dependent protein kinase (17). Activation of PKA initiates a cascade of

14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

P1: fhd

107

phosphorylation events through the activation of other downstream effectors. Collectively, these events trigger membrane and cytoskeletal rearrangements within

the parietal cell, as well as increase electrical conductance across the gastric epithelium (1). In the 1980s, several groups reported on stimulus-associated phosphorylation of parietal cell proteins, most of which were simply identified by molecular

size (18–21). By tracing the phosphorylation of proteins that occurred concomitant with stimulation of gastric glands by histamine, Urushidani and his colleagues

(19, 22) identified an 80-kDa peripheral membrane protein, later characterized as

the cytoskeletal-associated protein ezrin (23, 24), and a 120-kDa protein, now

called parchorin and recently implicated in Cl− and water transport (25, 26). In

addition, several stimulation-related phosphoproteins earlier identified by Chew

and her colleagues on the basis of molecular size (18, 27) are now recognized as

40-kDa lasp-1, 66-kDa coroninse (28), and CSPP-28, the latter being a calciumsensitive phosphoprotein of 28-kDa (29). Possible functional roles for each of

these phosphoproteins are discussed below.

The early studies of signaling processes related to acid secretion were carried

out on intact gastric glands. Because the plasma membrane provides a barrier

to separate intracellular environment from extracellular bath, the development of

permeable parietal cell models was important for a more direct manipulation of

cytosol. Several permeabilized models, in which electroporation (30) and digitonin

(30–33) were used to render gastric glandular cells permeable, have provided useful

information. However, none of these earlier permeabilized preparations could be

transformed from the resting to secreting state by the addition of secretagogues or

cAMP. This problem was eliminated by the use of α-toxin, isolated from Staphylococcus aureus, as a permeabilizing agent. The α-toxin permeabilized gastric gland

model can be triggered by cAMP to effect the resting-to-secreting transition that

is correlated with the phosphorylation, from 32P-ATP, of a dozen phosphoproteins

(34), several of which are similar to those mentioned above from the intact gland

studies.

The narrow pore size generated by α-toxin (∼3 nm in diameter) allows passage

of only small molecules such as nucleotides. Thus the α-toxin model has been

useful in studies of metabolism and protein phosphorylation associated with stimulation (34, 35), but access to large macromolecules is required for biochemical

reconstitution of parietal cell activation. To this end, several permeabilized systems have been developed to allow the introduction of large peptides and proteins

while retaining the resting-to-secreting transition in response to the addition of

cAMP. One system employing the detergent β-escin tested a variety of inhibitory

peptides that block the activities of several protein kinases, including PKA, PKC,

myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), and CaM kinase (36). These peptide inhibition experiments confirmed the roles of PKA and MLCK, but not CaM kinase and

PKC, in parietal cell secretion. In addition, the inclusion of peptides that inhibit

Arf (adenosine ribosylation factor) into β-escin-permeabilized glands was shown

to attenuate the cAMP-stimulated parietal cell activation, suggesting a functional

role for Arf protein in parietal cell secretion.

14 Jan 2003

13:55

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

108

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

An alternative model system has used the Streptococcal toxin streptolysin O

(SLO) to permeabilize gastric glands. With this model, Ammar et al. (37) were

able to show the incorporation of fluorescent-labeled actin into the pool of endogenous F-actin in SLO-permeabilized glands. They also tested the action of several

syntaxin isoforms on the cAMP-activated secretory response (as discussed below

in the section on SNARE proteins).

Yet another approach for permeabilized models is to use a depleted system,

such as the digitonin model, and probe for cytoplasmic constituents that restore

functional activity. Searching for players underlying the cAMP-mediated parietal

cell activation, Akagi et al. (38) carried out a reconstitution experiment in which

they added brain cytosol and purified fractions into digitonin-permeabilized gastric glands. They demonstrated a stimulatory activity by brain cytosol as judged by

aminopyrine uptake. The stimulatory activity was further characterized as phosphatidylinositol transfer protein (PITP). Although PITP is a stimulatory factor for

acid secretion, it is not associated with the cAMP-dependent pathway. This reconstitution model promises to be of importance for the further identification and

function of critical components necessary for parietal cell activation, including

other PKA effectors; it will also address questions of how known proteins such as

ezrin and lasp integrate the cAMP signal to membrane cytoskeleton remodeling.

Lasp-1 was initially identified in the parietal cell as a 40-kDa phosphoprotein

related to cAMP-mediated activation of acid secretion (18). Lasp-1 has been identified as a signaling molecule that is phosphorylated upon elevation of [cAMP]i in

pancreas and intestine, as well as gastric mucosa, and is selectively expressed in

ion-transporting cells within epithelial tissues, such as cortical regions of pancreatic

and salivary duct cells and in certain F-actin-rich cells in the distal tubule/collecting

duct (34, 35). Lasp-1 has been characterized as a new LIM protein subfamily member containing an N-terminal LIM domain, a C-terminal SH3 domain, and two

internal nebulin repeats, with speculation that lasp-1 may function as an adaptor

molecule to relay the upstream signaling to downstream effectors (39). Recent

biochemical evidence revealed that lasp-1 binds to nonmuscle filamentous (F)

actin, but not monomeric (G) actin, in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (40).

The apparent Kd of bacterially expressed his-tagged lasp-1 binding to F-actin was

2 µM, with a saturation stoichiometry of ∼1:7. Phosphorylation of recombinant

lasp-1 with PKA increased the Kd for lasp-1 binding to F-actin and decreased the

Bmax. The major PKA-dependent phosphorylation sites were localized in rabbit

lasp-1 to S99 and S146 (40).

Immunostaining of gastric glands stimulated by the cAMP-dependent pathway

showed that lasp-1 was redistributed from the basolateral membrane to the apical canalicular membrane of parietal cells upon stimulation (41). Alternatively,

exposure of gastric mucosal fibroblasts to the protein kinase C activator, PMA, induced the formation of lamellipodial extensions and nascent focal complexes that

contained both lasp-1 and F-actin (40). The selective phosphorylation-dependent

regulation of lasp-1 in F-actin-rich epithelial cells and the recruitment of lasp-1 to

cellular regions associated with dynamic actin turnover suggest that this protein

14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

P1: fhd

109

may play an integral and specific role in the regulation of cytoskeletal/membranebased cellular activities.

Parchorin was first identified by SDS-PAGE as a 120-kDa phosphoprotein associated with histamine/cAMP stimulation of acid secretion (19); the cDNA sequence of parchorin has recently been cloned, having an actual molecular mass of

65 kDa (26). Its anomalous migration on gels is due to an unusually high content

of acidic amino acids. Parchorin is a novel protein that has significant homology

to the family of chloride intracellular channels (CLIC) and has been localized to

a variety of epithelial tissues that are active in the transport of salt and water,

especially choroid plexus, salivary glands, and lacrimal glands, in addition to the

parietal cell (25, 26). Endogenous parietal cell parchorin is present in the cytosol

and relocated to the apical plasma membrane upon histamine stimulation, very

reminiscent of the translocation of H,K-ATPase in response to stimulation. When

parchorin, linked to green fluorescent protein (GFP), was exogenously expressed

in kidney cells, GFP-parchorin also appeared in the cytosol and was relocated to

the plasma membrane when Cl−efflux from the cells was triggered. Interestingly,

parchorin was co-purified with a new type of kinase activity (42), suggesting that

there may be some functional link between that kinase and the phosphorylated

form of parchorin.

Cholinergic Pathways of Activation

Activation of parietal cells by cholinergic agents acting on muscarinic M3 receptors

clearly involves an elevation of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i). Studies on isolated

gastric glands with Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent probes revealed a rapid spike in

parietal cell [Ca2+]i, up to 0.15–0.5 µM within 4–6 s after addition of the M3

agonist carbachol, followed by a sustained lower-level elevation of [Ca2+]i, that

persisted during the resulting stimulation of acid secretion by the glands (43, 44).

The secretagogue-dependent changes in [Ca2+]i occur from an intracellular store

of bound Ca2+ and are independent of extracellular Ca2+, unless the stores are first

depleted (45, 46). Buffering of the rise in [Ca2+]i by the chelating agent BAPTA

prevents the acid secretory response to carbachol but permits subsequent stimulation by histamine or forskolin (47). Intracellular Ca2+ stores are relatively easily

depleted by cholinergic stimulation in a Ca2+-free medium, although the stores can

be replenished from extracellular sources through a La3+-sensitive pathway (45).

The carbachol-induced rise in [Ca2+]i has been correlated with a rise in parietal

cell inositol trisphosphate (IP3) levels, thus implicating IP3 as the messenger from

the M3 receptor to the internal Ca2+ stores (43). The role of PKC in cholinergic

activation has been more controversial, particularly through the use of PKC activators such as phorbol esters (e.g., TPA), which have been shown to inhibit or activate

both carbachol- and histamine-stimulated acid secretion (48–51). Chew et al. (52)

measured the PKC expression in parietal cells, as well as the response of gastric

glands to a variety of PKC inhibitors. Their data showed several isozymes of PKC

present with some, particularly PKC-ε, being localized by immunocytochemistry

14 Jan 2003

13:55

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

110

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

to a parietal cell compartment similar to filamentous actin (52). Inhibitors of

PKC activity, such as Ro 31-8220, were found to potentiate both carbachol- and

histamine-mediated acid secretion, also causing a dose-dependent decrease in the

phosphorylation of the cytoskeletal-related proteins ezrin and pp66, later characterized as coroninse (28, 52). These data suggest a negative modulatory role for

PKC in acid secretion and were confirmed in principle by an independent study

(53), although there was some disagreement regarding responsiveness of specific

PKC isozymes.

A role for CaM kinase in parietal cell activation stimulated by the cholinergic

pathway was suggested by Tsunoda et al. (54) who found that KN-62, a pharmacological inhibitor of CaM kinase II, inhibited carbachol-mediated acid secretion,

but did not alter the rise in cytosolic Ca2+ caused by carbachol. KN-62 was without

effect on histamine- or forskolin-mediated responses (55). The presence of CaM

kinase II in gastric cells was verified by enzymatic assay (54).

The calcium-sensitive phosphoprotein of 28 kDa known as CSPP28 was originally discovered based on its phosphorylation associated with cholinergic stimulation (27). CSPP28 is rapidly phosphorylated in intact parietal cells in response to both the cholinergic agonist, carbachol, and the calcium ionophore,

ionomycin (29). Subsequent studies showed that recombinant CSPP28 was phosphorylated by both crude parietal cell homogenate and purified CaM kinase II in

a calcium/calmodulin-dependent manner (29). Whereas CSPP28 is closely tied to

a calcium-mediated phosphorylation, it would be of great interest to ascertain the

nature of CaM kinase-mediated phosphorylation on CSPP28 and whether such

modification regulates the function of CSPP28 in the activation process.

Carbachol has been shown to induce IκB kinase activity in canine parietal

cells via Ca2+- and PKC-dependent pathways (56). IκB kinase appears to be a

key element in the signaling cascade that activates NF-κB (57, 58), which is an

important transcription factor and regulator of numerous genes modulating the

inflammatory response. Carbachol is also a potent inducer of several families of

protein kinases known as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) or extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERKs) and the c-Jun N-terminal protein

kinases (JNKs) in the canine parietal cell system (59–61). Generally, these kinases

are known to be fundamental signaling elements in cellular functions of growth,

differentiation, and secretion (62–65). However, it is uncertain as to what specific

role these kinases play in the acid secretory activation pathway because presumed

specific inhibitors of the various kinases reportedly produce both inhibitory and

enhancing effects. For example, a pronounced up-regulation of p38 kinase, another

member of the MAPK family of protein kinases, occurred in response to carbachol and could be blocked by the p38 kinase-specific inhibitor SB-203580 (66).

Interestingly, carbachol-induced aminopyrine uptake by intact canine parietal cells

was potentiated several-fold by SB-203580, suggesting that active p38 kinase was

inhibitory to acid secretion (66). Collectively these data demonstrate the extensive

interrelationship of signaling elements that are activated via M3-muscarinic stimulation of gastric parietal cells. It remains to be established which elements are

14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

P1: fhd

111

directly involved in the activation of parietal cell secretion, which are modulatory

or inhibitory to the activation, and which are true downstream effector proteins

rather than secondary and tertiary reporters of changes in metabolic load.

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

Modulation by EGF and TGF-α

To reveal the mechanisms underlying the actions of EGF and TGF-α on acid secretion, Chew et al. (67) studied the effects of these agents on isolated parietal cells

and primary cultures. They categorized two apparently opposed responses: (a) an

acute inhibition of histamine- and carbachol-mediated acid secretion and (b) an enhancement of acid secretory function with chronic exposure to the growth factors.

Because of the observed differential effects of the acute and chronic responses to

tyrosine kinase inhibitors, they proposed that EGF and TGF-α modulate parietal

cell function by multiple signaling pathways. They reasoned that a soluble tyrosine

kinase was involved in mediating the chronic effects of EGF, whereas the acute

potentiation of histamine-stimulated secretion by certain tyrosine kinase inhibitors

was probably not mediated by receptor-associated tyrosine kinases. In a further

study of these growth factors on parietal cell activation, these authors showed that

EGF biphasically activated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases, known

as ERK-1 and ERK-2, with a peak response occurring at approximately 5 min,

followed by a sustained activation for at least 2 h (68). In contrast to EGF, the phorbol ester PKC activator TPA induced a sustained activation of ERK-1 and ERK-2

for at least 2 h. Carbachol also activated ERK-1 and ERK-2, but the response was

weaker and monophasic. However, the ERK-signaling cascade was not modulated

by elevated intracellular free Ca2+ or cAMP.

Takeuchi et al. (59, 60) confirmed the biphasic effects of EGF on isolated canine

parietal cells and tested the role of ERKs as possible signal modulators for gastric

secretion. In their studies, carbachol caused a pronounced increase in the kinase

activity of ERK2 in extracts prepared from canine parietal cells (gastrin and EGF

had modest effects, and histamine had no effect), but unlike Chew’s group, these

authors found that the stimulatory response to carbachol appeared to be dependent

on elevated [Ca2+]i and that a specific inhibitor of ERK, PD-98059, abolished the

stimulatory response. Addition of the ERK inhibitor to intact parietal cells led to a

modest elevation, at best, of aminopyrine uptakes stimulated by carbachol or other

secretagogues, thus the ERK pathway has a minimal role in the direct activation

of gastric secretion. This conclusion is supported by later work suggesting that

the increased ERK activity stimulated by EGF appears coupled to H,K-ATPase

α-subunit expression (69) which may be the reason for the slightly enhanced

secretory activity associated with ERK activation and may even form the basis for

the long-term stimulatory effects of EGF. The serine-threonine protein kinase Akt

appears to be another element in the EGF activation cascade leading to increased

H,K-ATPase expression in canine parietal cells (70).

Tsunoda et al. (71) employed chemical inhibitors of tyrosine kinases, genistein and erbstatin, to test for their ability to release the parietal cell from the

14 Jan 2003

13:55

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

112

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

inhibitory action of EGF/TGF-α on acid secretion. Whereas these two inhibitors

totally abolished the TGF-α-mediated inhibition, genistein but not erbstatin, also

potentiated histamine- and forskolin-triggered acid secretion. Because genistein

is a relatively selective inhibitor for cytosolic tyrosine kinases such as c-src, it is

likely that some cytosolic tyrosine kinase negatively regulates parietal cell secretion. It has been reported that activation of tyrosine kinase such as c-src stimulates

the dynamin-dependent endocytosis of renal outer medullary potassium channels

(72). It is possible that EGF/TGF-α exert their inhibition on histamine-stimulated

acid secretion by promoting the retrieval of H,K-ATPase from the apical plasma

membrane. Although a tyrosine residue in the cytoplasmic tail of the β-subunit

of H,K-ATPase has been implicated in proton pump recycling (73), it would be

of great interest to test whether tyrosine kinases such as c-src accelerate the recycling of H,K-ATPase and to ascertain the molecular mechanism underlying the

regulation of H,K-ATPase recycling by tyrosine phosphorylation.

Modulation by Duodenal and Neural Peptides

Physiological modulation of gastric secretion by a variety of peptides, including

the duodenal hormone cholecystokinin (CCK) and the neuropeptide vasoactive

intestinal peptide (VIP), has been well established. Of prime importance for the

action of CCK and VIP is the paracrine release of somatostatin by D cells in the

antrum and fundus (74, 75). Some of the effects of somatostatin are peripheral to

parietal cells, e.g., inhibit release of gastrin from antral G cells (75, 76) and inhibit

release of histamine from fundic ECL cells (77, 78), but somatostatin also has

direct inhibitory effects on parietal cells (79, 80). Somatostatin receptors on the

parietal cell have been characterized as sstR2-type receptors (84), which operate

via an inhibitory guanine nucleotide-binding protein (Gi) to attenuate the activity

of adenylate cyclase. Inhibition of Gi by pertussis toxin reversed the ability of

somatostatin to inhibit acid secretion and restored the adenylate cyclase-mediated

production of cAMP by isolated canine parietal cells stimulated with histamine and

forskolin, but did not alter the stimulatory effects of dbcAMP or Ca2+ pathway

(79, 82). In addition somatostatin may have long-term effects on parietal cells

because it has been shown to inhibit expression of early response genes, such as

c-fos, via a pertussis toxin-sensitive inhibitory pathway in isolated canine parietal

cells (83, 84).

TRAFFICKING OF H,K-ATPASE ASSOCIATED WITH

ACID SECRETION

In the resting parietal cell the proton pump resides in cytoplasmic tubulovesicles in

an inactive form, presumably because of low permeability of these membranes to

K+ (85). Upon stimulation by secretagogues, H,K-ATPase translocates and inserts

into the apical plasma membrane which has, or acquires, K+ and Cl− conductance

21 Jan 2003

11:26

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

P1: fhd

113

pathways that lead to active proton pumping. H,K-ATPase is a P-type ATPase

composed of a catalytic subunit (α-subunit) and an accessory subunit (β-subunit).

The H,K-ATPase catalyzes the electroneutral exchange of intracellular protons

for extracellular potassium ions, thus generating the enormous proton gradients

associated with gastric HCl secretion (1, 86). Early EM studies support a model

in which H,K-ATPase-containing vesicles fuse with the apical plasma membrane

upon stimulation, thus recruiting the pump enzyme into the plasma membrane

(87). In the following section we discuss those protein elements that have been

identified in parietal cells and have been shown (or implicated) to have a role in

directing the trafficking and recycling of H,K-ATPase-rich membranes underlying

HCl secretion. Figure 1 provides a cartoon summary of the membrane recycling

scheme, indicating the location of putative participating proteins.

SNARE Proteins

It is widely accepted that the fundamental components of the machinery required

for membrane fusion are highly conserved in both constitutive and regulated membrane trafficking pathways (88, 89). These components include N-ethylmaleimidesensitive factor (NSF), the soluble NSF attachment proteins (α-, β-, and γ -SNAPs),

and SNAP receptors (SNAREs). Membrane-associated SNAREs were first identified in detergent extracts of brain membranes (90). In these extracts, the SNAREs

formed a tightly bound complex consisting of SNAP-25, syntaxin, and a protein

known as vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP). The specific cleavage

of each of these proteins by specific neurotoxins causes a blockade in neurotransmitter release, indicating that SNAP-25, syntaxin, and VAMP are essential

for exocytosis in synaptic termini (91). Peng et al. (92) showed that a syntaxin

isoform known as syntaxin 3 and the VAMP-2 isoform (also known as synaptobrevin) are specifically associated with H,K-ATPase-containing tubulovesicles in

gastric parietal cells, suggesting their possible involvement in secretory activation.

Calhoun & Goldenring (93) and Calhoun et al. (94) confirmed the localization of

syntaxin 3, VAMP-2, and another secretory carrier membrane protein known as

SCAMP to the tubulovesicle fraction, and more importantly demonstrated their relocation to the apical plasma membrane after stimulation. Because these data were

consistent with a role for syntaxin 3 in apical trafficking of H,K-ATPase, Ammar

et al. (37) carried out experiments in which recombinant syntaxin 3 was added

into SLO-permeabilized gastric glands as a potential competitor for endogenous

SNARE complex formation. Significantly, exogenous syntaxin 3, but not the syntaxin 5 isoform, blocked cAMP/ATP-mediated HCl secretion in a dose-dependent

manner. The authors reasoned that the soluble exogenous syntaxin 3 reacted with

endogenous cognate SNAREs to prevent the recruitment of secretory pumps, thus

providing direct evidence for the involvement of the syntaxin 3 isoform in parietal

cell activation.

Primary cultures of parietal cells have been particularly useful in defining the

trafficking and recycling of membrane components associated with stimulation of

14 Jan 2003

13:55

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

114

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

acid secretion (95). Karvar et al. (96) used an adenovirus-based GFP reporter to

show that GFP-VAMP-2 is co-localized with H,K-ATPase to cytoplasmic membranes of resting parietal cell cultures and that GFP-VAMP-2 is translocated along

with the pump enzyme to the apical plasma membrane after stimulation by histamine. To test the involvement of VAMP-2 in parietal cell activation, they treated

SLO-permeabilized glands with tetanus toxin, which is a highly specific protease for VAMP proteins. They demonstrated a correlation between the cleavage

of VAMP-2 and the inhibition of glandular acid secretion, confirming an earlier

suggestion that the proteolytic cleavage of VAMP-2 inhibited acid secretion in

isolated parietal cells that were permeabilized by SLO and stimulated with cAMP

(97). Further support for the participation of SNARE proteins in the recruitment of

H,K-ATPase is offered by recent studies of Karvar et al., who doubly infected parietal cell cultures with genes constructed with different fluorescent proteins linked

to VAMP-2 and SNAP-25 (98). In resting cells, the two proteins were localized

to different membrane compartments: VAMP-2 to H,K-ATPase-rich cytoplasmic

vesicles, and SNAP-25 to apical membrane vacuoles. Upon stimulation with histamine, the two signals became coincident in the expanded plasma membrane

consistent with SNARE complex formation associated with membrane recruitment. Furthermore, introduction of a SNAP-25 construct lacking the functional C

terminus inhibited acid secretion by the isolated cells.

Rab Proteins

In addition to SNARE proteins, small GTPase proteins have long been implicated

in vesicular membrane trafficking (99). Studies in several systems, primarily in

neuronal synapses, have demonstrated that Rab3 family members redistribute from

a membrane-bound location to the soluble cytosolic fraction upon fusion of secretory granules with target plasma membranes. Rab proteins are then recycled back

onto mature secretory vesicles after reinternalization of the membrane. Although

this cycle is well established for Rab3, far less is known about the functional activity of other Rab proteins during vesicle fusion and recycling. In the gastric parietal

cell, there are several Rab proteins, including Rab11 and Rab25 (93, 100, 101). In

nonsecreting parietal cells, the Rab11a isoform is associated with H,K-ATPasecontaining tubulovesicles that fuse with the apical plasma membrane in response

to secretory agonists such as histamine (94).

Using matrix-assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry, Duman et al. (102)

confirmed that Rab11 is associated with H,K-ATPase-enriched gastric microsomes, and their data provided a stoichiometric estimate of one Rab11 per six

copies of H,K-ATPase. Furthermore, Rab11 exists in at least three forms on rabbit

gastric microsomes: The two most prominent resemble Rab11a, whereas the third

resembles Rab11b. Using an adenoviral expression system, Duman et al. expressed

the dominant-negative mutant Rab11a N124I, in primary cultures of rabbit parietal cells. Rab11a N124I is a mutant of Rab11a in which aspargine (N) at position

124 has been replaced with isoleucine (I). The mutant was well expressed with a

14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

P1: fhd

115

distribution similar to that of H,K-ATPase in resting parietal cells; however, mutant

Rab11a arrested the stimulus-dependent morphological transition of the parietal

cells and acid secretion measured by aminopyrine uptake. Specificity was verified

by addition of tetracycline, which blocked mutant Rab expression and restored the

morphological transition and acid secretory function. These studies demonstrate

that Rab11a is a prominent GTPase associated with gastric tubulovesicles and

suggest that it plays a direct role in regulating parietal cell activation.

In a search for downstream effectors, a number of Rab11-interacting proteins

have been identified as co-enriched with Rab11a and H,K-ATPase on parietal cell

tubulovesicle membranes: rab11-family interacting protein 1 (rab11-FIP1), rab11family interacting protein 2 (rab11-FIP2), and pp75/rip11 (103). The binding of

rab11-FIP1 and rab11-FIP2 to Rab11a was dependent upon a conserved C-terminal

amphipathic α-helix. Moreover, these Rab11-interacting proteins were found to

translocate with Rab11a and the H,K-ATPase upon stimulation of parietal cells with

histamine. These results suggest that the function of Rab11a in plasma membrane

recycling is dependent upon a number of protein effectors.

Clathrin Coat and Other Adaptor Proteins

An important, though somewhat ignored, aspect of regulating gastric secretion

has to do with the uptake and internalization of the extensive apical membrane

when the stimulus is withdrawn and the parietal cell returns to the resting state.

Given the similarities of regulated H,K-ATPase trafficking with recycling of cargo

through the apical recycling endosomes of many epithelial cells, it seems reasonable to speculate that clathrin and its adaptor proteins regulate some part of an

apical recycling pathway as in other epithelial cells. Using immunological probes,

Okamoto et al. (104) identified γ -adaptin and clathrin heavy chain on tubulovesicles isolated from gastric parietal cells. Further biochemical characterization of

the tubulovesicular clathrin adaptor complex suggested a subunit composition including α-, β- and γ -adaptins, as well as other subunits with molecular masses

of 50 and 19 kDa, all of which could polymerize in vitro into basket-like structures of ∼120 nm diameter (105). For parietal cells in the nonsecreting state,

immuno-electron microscopy revealed that clathrin is relatively abundant at or

near the apical canalicular membrane specifically in association with coated pits

and coated vesicles, as well as accumulated at the ends of tubulovesicular profiles where the membranes are acutely curved. These results indicate that, even in

resting cells, active membrane trafficking between the apical membrane and the

tubulovesicular compartment is an ongoing process. They are also consistent with

an hypothesis that the secretory cycle is regulated with respect to the relative rates

of exocytic (stimulation) and endocytic (recycling) processes, rather than a binary

on or off system. It must be pointed out that, although clathrin and its adaptors are

well represented and appear actively involved in some aspect of apical membrane

recycling in the parietal cell, there is only presumptive evidence that H,K-ATPase

is the cargo.

14 Jan 2003

13:55

116

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

Dynamin

Another component of clathrin-dependent trafficking pathways is the large

GTPase dynamin, which is essential for receptor-mediated endocytosis and is

clearly known to interact with clathrin and coat-forming proteins, but its precise

function in vesicle formation remains controversial (106, 107). Given the distribution of clathrin and clathrin adaptors in the parietal cell, it is not surprising that

a dynamin-like molecule should be associated with the apical membrane. In fact,

dynamin II has been immunolocalized to the apical membrane of both resting

and stimulated parietal cells (94, 105). Interestingly, among the various cell types

in gastric glands, dynamin appears to be expressed predominantly, if not exclusively, in the parietal cell (105). Although it has been proposed that dynamin acts

as a “pinchase” for constriction of endocytic membrane separation from plasma

membrane, this remains to be established (107).

Using a GST-dynamin II fusion protein as an affinity matrix, Okamoto et al.

identified two proteins that bind to dynamin II, the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase

c-src and lasp-1 (108). Moreover, the binding of c-src and lasp-1 was specific for the

proline-rich domain of dynamin II. Their study also showed the presence of c-src

on tubulovesicular membranes, with an active tyrosine kinase that phosphorylated

tubulovesicular proteins in vitro, one of which may be the 100-kDa H,K-ATPase.

A potential trafficking role for c-src on tubulovesicular membranes is of interest because c-src has been found on endosomal membranes (109), as a regulator

of other apical membrane trafficking pathways (110, 111), and shown to regulate membrane transporters directly by phosphorylation (112). The interaction of

lasp-1 with dynamin II is also of interest, suggesting the possibility of some regulatory role for lasp-1 in coordinating the actin cytoskeleton and vesicular trafficking

machinery via dynamin (108). As with c-src, the functional consequences of lasp-1

dynamin II interaction remain to be characterized.

Although these interactive data provide interesting possibilities for connection

between signaling molecules such as c-src and the downstream effectors, such

as dynamin, lasp-1 and even H,K-ATPase, the role of the in vitro protein-protein

interactions in parietal cell physiology and their regulation during cell activation

remain to be characterized.

Myosin Vb

Given the importance of Rab11a in tubulovesicle trafficking, Lapierre et al. (113)

set up a yeast two-hybrid screen for proteins interacting with active Rab11a.

Among three Rab11-interacting proteins discovered, one is myosin Vb. These

authors further characterized myosin Vb in polarized MDCK cells. They found

that myosin Vb is associated with apical endosomes. Furthermore, this association depends on the integrity of microtubules, providing the interesting suggestion

of a role for myosin Vb in plasma membrane recycling in connection with the

microtubule cytoskeleton. Expression of the C-terminal tail of myosin Vb dispersed the distribution profile of transferrin receptor and retarded recycling of the

14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

P1: fhd

117

receptor back to the plasma membrane. By analogy with a proposed function of

myosin Va in melanosome trafficking (114), it is also possible that the mutant

disrupted the association of the myosin Vb-endosomal complex with the actinbased cytoskeleton, which resulted in an inhibition of apical plasma membrane

recycling.

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

Structure and Function of H,K-ATPase

H,K-ATPase shares several structural homologies with another P-type ATPase,

Na,K-ATPase (86, 115). They are both composed of an α-subunit, predicted to

span the membrane 10 times, and a glycosylated β-subunit of type II integral

membrane protein. Early in the biosynthetic pathway, the β-subunits assemble with

α-subunits in the endoplasmic reticulum. Assembly of the holoenzyme appears to

involve interactions between cytoplasmic, extracytoplasmic and transmembrane

domains of both subunits (116, 117) and requires insertion of the α/β complex

into the plasma membrane. Although cross-assembly of H,K-ATPase and Na,KATPase subunits can occur under contrived in vitro conditions, the α-subunit of

each ATPase preferentially assembles with its respective β-subunit (118).

Whereas the amino acid sequence between the H,K-ATPase and Na,K-ATPase is

highly conserved, these enzymes differ in several important attributes, including the

cations they respectively transport and their targeted locations. The Na,K-ATPase

is concentrated at the basolateral membrane of most epithelial cells, whereas, the

gastric H,K-ATPase is ultimately targeted to the apical membrane of secreting

parietal cells. Also, the H,K-ATPase represents the major cargo protein for the

regulated recycling associated with acid secretion.

The recruitment of vesicular coat proteins has been shown to depend upon both

the presence of membrane protein cargo and the lipid composition of the target

membranes (119). Thus cargo can regulate the formation of vesicular carriers.

Complete deletion of either the α-subunit (120) or the β-subunit (121) in knockout

mice was shown to have predictably profound effects on parietal cell structure and

function. In both cases, the mice were achlorhydric. Although parietal cells were

histologically identifiable, both knockout mice exhibited a dramatic diminution

of tubulovesicular membranes. The residual amount of β-subunit expressed in the

α-subunit knockout mice was not sufficient to produce a tubulovesicular network

(120), suggesting that the assembled holoenzyme is required as cargo for the

biogenesis of the tubulovesicular compartment.

Expression studies in heterologous cell lines have shown that the α-subunit

of the gastric H,K-ATPase encodes sorting and targeting information responsible

for the apical distribution of the pumps. By analyzing the sorting behavior of a

number of chimeric pumps composed of complementary portions of β-subunits

from the H,K-ATPase and Na,K-ATPase, Dunbar et al. (122) identified a portion

of the gastric H,K-ATPase, which is sufficient to redirect the normally basolateral

Na,K-ATPase to the apical surface in transfected LLC-PK cells. This motif resides

within the fourth of the ten predicted transmembrane domains of the α-subunit.

14 Jan 2003

13:55

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

118

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

There are seven N-glycosylation sites on the β-subunit of the H,K-ATPase

(123). To examine the role of the carbohydrate chains on holoenzyme activity and

stability, Asano et al. (124) carried out site-directed mutagenesis on the β-subunit

in which one, several, or all of the asparagine residues in the N-glycosylation sites

were replaced by glutamine. Removing any one of seven carbohydrate chains from

the β-subunit did not have a significant effect on the activity of H,K-ATPase or

its delivery to the apical surface. However, removal of all the carbohydrate chains

prevented assembly of the holoenzyme and all associated functional activity. In

contrast, enzyme activity and α/β-subunit assembly were retained when three

carbohydrate chains were removed, but surface delivery of the β-subunit and its

associated α-subunit was arrested, indicating that the surface delivery mechanism

is more dependent on the carbohydrate chains than is the expression of H,K-ATPase

activity and holoenzyme assembly.

In addition to stabilizing its complementary α-subunit, the β-subunit of

H,K-ATPase may contain a tyrosine-based endocytotic motif that is essential for

recycling of the pump after withdrawal of stimulation. Courtois-Coutry et al. (73)

made transgenic mice that expressed a mutant H,K-ATPase β-subunit, in which a

critical tyrosine residue in the cytoplasmic tail was mutated to alanine. These mice

developed a pathology resembling that in idiopathic hypersecretion of acid into

the stomach. Immuno-electron microscopy data suggest that the β-subunit, and

presumably the α-subunit, in these transgenic mice are constitutively expressed at

the apical membrane and fail to re-internalize. The authors concluded that that the

mutated β-subunit, and therefore the pump enzyme, could not interact with the

endocytotic machinery to allow re-sequestration of the stimulated apical surface

in reversion to the resting state.

Biochemical studies suggest that the cytoskeletal proteins ankyrin and spectrin

interact with the H,K-ATPase in the microsomal fraction of resting parietal cells

and appear to relocate with H,K-ATPase to the apical plasma membrane of the

secreting parietal cells (125). Whereas these authors speculated that ankyrin and

spectrin form a functional complex to stabilize H,K-ATPase at the apical membrane

upon the stimulation, it would be of great interest to ascertain whether ankyrin and

spectrin directly bind to H,K-ATPase and how such interactions are regulated.

ACTIN-BASED CYTOSKELETON IS ESSENTIAL

FOR PARIETAL CELL ACTIVATION

Actin

Interactions between the plasma membrane and the cytoskeleton play a central

role in a variety of physiological processes including mobilization of membrane

receptors, endocytosis, exocytosis (e.g., hormone secretion and transmitter release), cell polarity, and morphology (126, 127). An essential role for the cortical

actin cytoskeleton in parietal cell secretion has been implied from morphological

14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

P1: fhd

119

analyses (1–3) and from studies with microfilament disrupters such as cytochalasin (128, 129). Highly organized microfilaments are a characteristic feature of

microvilli within the canaliculus of the gastric parietal cell. However, the radial

arrangement of the actin filaments in proximity to the microvillar membrane in

parietal cells (3) is distinctly different from the central core localization of actin

filaments of intestinal microvilli (130).

The actin gene family encodes a number of structurally related, but functionally

distinct, protein isoforms that modulate contraction in muscle tissues and control

shape and motility of nonmuscle cells (131). In mammals, there are at least six

different actin isoforms, each encoded by a separate gene, and they differ by

<10% of the amino acid sequence, primarily in the N-terminal region (132).

The development of cytoplasmic β- and γ -actin isoform-specific antibodies has

provided powerful tools for localizing actin isoforms in situ (133).

Using actin isoform-specific antibodies and isolated gastric glands as an epithelial model, Yao et al. (134) demonstrated that actin isoforms, in particular

the cytoplasmic β- and γ -actin nonmuscle isoforms, are differentially polarized

in epithelial cells. They found that β-actin was predominantly localized to the

apical plasma membrane of all glandular cells, including the tortuous microvillienriched canalicular surface of parietal cells, as well as the entire gland lumen,

whereas γ -actin was predominantly localized to the basolateral membrane.

The canaliculi of resting parietal cells are replete with short microvilli that

include radially organized actin microfilament bundles projecting along the microvillus and extending one or more micrometers into the cytoplasm (3). The

radical membrane transformations of cell activation result in elongation of microvilli, which suggests a commensurate shift in the ratio of monomeric G-actin

to filamentous F-actin. However, measurements on the state of actin in gastric

glands revealed the following: (a) Parietal cell actin is primarily organized in the

F-actin form (90%); (b) the microfilament disrupter cytochalasin D destabilizes

the F-actin and inhibits acid secretion; and (c) phalloidin, which stabilizes F-actin

filaments, does not inhibit acid secretion (135). Surprisingly, the authors could find

no significant change in the ratio of F- to G-actin when the cells were transformed

from rest to maximal secretion: F-actin remained about 90% of the total. These

data are consistent with an hypothesis that microfilamentous actin is necessary for

membrane recruitment underlying parietal cell secretion; however, they suggest

that rapid exchange between G- and F-actin is not essential for the secretory process and that the parietal cell maintains actin in a highly polymerized state. This

conclusion was underscored by the work of Ammar et al. (136) who tested the actin

monomer-sequestering agent latrunculin B (Lat B) on parietal cell structure and

function. Lat B inhibited acid secretion and increased the extractable monomeric

actin but only at relatively high doses (10–70 µM). Because the authors observed

high sensitivity of other parietal cell functions to Lat B (e.g., formation of lamellipodia was inhibited at 0.1 µM), they reasoned that there were distinct pools of

exchangeable actin in parietal cells, with microvillar microfilaments being particularly stable owing to the presence of stabilizing, capping, and bundling proteins.

14 Jan 2003

13:55

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

120

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

They proposed that the resistance of acid secretory function to Lat B is the result

of stable actin filament-turnover pathways that minimize the accessibility of the

actin monomer to Lat B.

The actin cytoskeleton has been linked to the mechanism of potentiation of

cAMP-mediated acid secretion by carbachol in rabbit gastric glands (137). The

observed potentiation was dependent upon release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores

regulated by the type 3 IP3 receptor (the major subtype in the parietal cell), but

it was unaffected by changes in extracellular Ca2+ or inhibitors of either PKC or

CAM kinase II. On the other hand, the disrupter of actin filaments, cytochalasin D, preferentially blocked the secretory effect of carbachol and its synergism

with cAMP, as well as the release of Ca2+ from stores. Treatment of glands

with cytochalasin D also caused redistribution of the IP3 receptor from a plasma

membrane-like fraction to the microsomal fraction, suggesting a dissociation of

the stores from the plasma membrane and a functional coupling between actin

filaments and the receptor-mediated Ca2+ store.

Ezrin-Actin Interactions

An actin-binding/regulatory protein that may have a primary role in parietal cell

function was mentioned above as the stimulation-dependent 80-kDa phosphoprotein called ezrin. Ezrin was independently identified by various investigators

for their special interests (138–140) and implicated as a cytoskeleton-membrane

linker protein. Ezrin is the best studied member of the ERM (ezrin-radixin-moesin)

family (141). These proteins share approximately 75% primary sequence identity

and contain an N-terminal globular domain followed by an α-helical region and

a C-terminal tail domain (142). Although ezrin was originally purified with the

microfilament bundles from intestinal microvilli, the native, full-length protein

possessed no convincing F-actin binding activity in tests that used α-actin from

skeletal muscle, a commonly used rich source of pure actin. However, C-terminal

fragments of ezrin were shown to bind filamentous α-actin (143); consequently,

Bretscher et al. (142) developed a model of intra- and intermolecular folding of

full-length ezrin to account for the discrepancy.

Ezrin was first identified in parietal cells on the basis of PKA-dependent phosphorylation concomitant with stimulation of gastric glands (19, 22). Double immunostaining for ezrin and for β-actin revealed that these two proteins are abundant

and primarily co-localized to the same regions within parietal cells, characteristic of the tortuous apical canalicular surface wending through most of the cell

(23, 24, 134). Interestingly, ezrin is almost exclusively localized to parietal cells,

whereas staining for the β-actin isoform is intense along the apical borders of all

cell types lining the gland lumen as well as within apical canaliculi of parietal

cells. Because the γ -actin isoform is primarily distributed near the basolateral

membrane of parietal cells (134), it appears that ezrin is co-localized with β-actin,

but not γ -actin, as a subset of the F-actin microfilaments.

On the basis of actin-ezrin cyto-localization studies and the knowledge that

α-actin is not expressed in parietal cells, Yao et al. (144) hypothesized that ezrin

14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

P1: fhd

121

preferentially binds to nonmuscle actin isoforms rather than to skeletal muscle

α-actin. Using a co-sedimentation assay that compared purified β-actin with skeletal muscle α-actin, ezrin appeared in the pellet only when β-actin was polymerized, whereas a known actin-binding protein, the S1 tryptic fragment of myosin II,

showed no selectivity between these actin isoforms. The calculated data suggest a

stoichiometry of 1 ezrin bound per 12 actin molecules. These studies indicate that

gastric ezrin possesses F-actin binding in an isoform-specific manner. In fact, the

binding of full-length ezrin to actin was lately demonstrated using a novel solid

phase actin-binding assay (145).

In their search for a novel class of pharmacological antiulcer agents, Urushidani

et al. (146) reported that a compound designated ME3407, a potent acid secretion

inhibitor, arrested the morphological transition of cells stimulated by histamine.

Because ME3407 was found to liberate the phosphoprotein ezrin from the apical plasma membrane, as well as to inhibit histamine-triggered translocation of

H,K-ATPase, these authors hypothesized that ME3407 may exert its inhibitory

action on the modulation of protein phosphorylation required for recruitment of

H,K-ATPase. Dephosphorylation of ezrin has been correlated with its dissociation

from the plasma membrane-cytoskeleton (147). ME3407 was also observed to inhibit MLCK and PI3 kinase activities measured in vitro (44). Because wortmannin

is a well known inhibitor of these latter kinases, it was tested and found to inhibit

glandular acid secretion, similar to the effect of ME3407. Recent studies, however,

have differentiated the effects of wortmannin and ME3407 (37). Both compounds

were found to inhibit acid secretion by intact gastric glands, but only ME3407

e inhibited acid secretion in SLO-permeabilized glands and liberated ezrin from

its membrane-cytoskeletal locus at the canalicular surface. Thus it appears that

the targets of these two inhibitors are not identical. Future studies may attempt to

define whether and to what extent phosphorylation of ezrin might be altered by

ME3407 and relate it to the modulation of parietal cell secretion.

Ezrin Interacts with Other Cellular Proteins

Using an overlay assay, Dransfield et al. (148) showed that ezrin binds to the

regulatory RII subunit of PKA in parietal cells, suggesting it might be involved in

the functional localization of PKA as an anchoring protein. In addition, the authors

showed that the RII subunit of PKA is capable of binding to full-length ezrin in

cell extracts, arguing that inter- or intramolecular interaction of ezrin masks ezrin

activity in binding to other cellular proteins. It was also reported that the N-terminal

domain of ezrin binds to EBP50, which mediates ezrin association with the plasma

membrane, although the physiological relevance of such interaction remains to be

characterized (144).

In a search for Ca2+-mediated signaling events in parietal cell activation, Yao

et al. (149) discovered the presence of calpain I (µ-calpain) in gastric parietal cells

and its interaction with ezrin. Further studies showed that parietal cell calpain

I can be activated by an ionomycin-mediated elevation of intracellular calcium;

furthermore, the activation of calpain triggers the release and hydrolysis of ezrin

21 Jan 2003

11:27

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

122

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

(149), followed by the collapse of the actin cytoskeleton in parietal cells. These

studies suggest the importance of ezrin in the integrity of the actin cytoskeleton of

parietal cells. Significantly, the activation of calpain, as evidenced by the hydrolysis

of ezrin, was correlated with the inhibition of parietal cell secretion, presumably

through the loss of ezrin. This ezrin-calpain interaction is unique because the

calpain cleavage site is located to the C-terminal 200 amino acids of ezrin where

sequences of the ERM family are divergent. To explore the possible regulation

by calcium and calpain I of the interaction between β-actin and ezrin, Herman

and his associates overexpressed calpastatin, an endogenous inhibitor of calpain,

in fibroblast cells. The overexpression resulted in a diminished calpain activity

and increased ezrin protein level, which was experimentally correlated with an

inhibition of filopodial formation (150), suggesting that spatial activation of calpain

may be necessary for actin dynamics associated with spreading at the leading edge.

It will be of interest to evaluate whether the hydrolysis of ezrin, or the liberation of

ezrin from actin cytoskeleton, is essential for formation of cytoplasmic extensions

such as filopodia or microvilli.

A NOTE ON THE FUSION REACTION

Thus far we have discussed the signal transduction events of parietal cell activation

in terms of (a) the structural elements (cytoskeleton) that support and promote the

translocation of H,K-ATPase-rich membranes from their cytoplasmic location to

the apical membrane and (b) the cognitive elements (SNAREs) that assure membranes are directed to and associate with highly specific docking sites. (c) A third

and equally important element has generally been given less attention, the fusion

mechanism itself, i.e, the means by which two distinct apposing lipid bilayers

interact and flow into one. A schematic view of these three cooperative processes

contributing to membrane recruitment is shown in Figure 2. The proposal that

phospholipid surface chemistry and fusion processes play a role in membrane

recruitment and secretion extends back to 1963, when morphological transformations of acid-secreting cells were correlated with phospholipid turnover in bullfrog

gastric mucosa (87). Although this was an important step in formulating the membrane recycling hypothesis, little work was done on the fusion process per se until

recently. Using separate assays of fluorescence dequenching and intervesicular

protein transfer, Duman et al. (151) have demonstrated that gastric tubulovesicular

membranes will fuse with each other (homotypic fusion) or with liposomes of

the appropriate composition. The fusion reaction is highly specific for a triggering system that must include either Ca2+ or ATP (EC50 is 0.15 µM and 1 mM,

respectively) and is dependent on the presence of protein in at least one of the

two vesicular pools, although the specific protein has not been identified. Whereas

these in vitro fusion data are preliminary, they do offer a system by which the

interfacial reactions of fusion might be studied, with the potential to identify new

classes of proteins that facilitate the lipid mixing processes.

14 Jan 2003

13:55

AR

AR177-PH65-05.tex

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

CELL BIOLOGY OF ACID SECRETION

P1: fhd

123

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

PERSPECTIVES

Although great progress has been made over the past 10 years in characterizing

the mechanisms and participants in parietal cell secretion, the challenge ahead is

to define the precise function and the physiological regulation of the implicated

proteins and identify new players (152). By analyzing both the cell biology and

physiology of phenotypic changes in cultured parietal cells and even transgenic

animals expressing mutant regulatory proteins, it will be possible to determine

whether and how a particular molecule operates upon the signaling cascade and

downstream effector reactions of parietal cell activation. Molecular engineering

of fluorescent reporters on a desired molecule has emerged as an exciting way to

correlate the cytological changes to molecular function of individual regulatory

proteins in real-time imaging of live parietal cells. Such studies will consolidate

protein-protein interactions that have been inferred from indirect techniques into

a physiological model for parietal cell activation and relate these data to molecular medicine of associated disorders such as peptic ulcer disease and gastric

carcinoma.

The Annual Review of Physiology is online at http://physiol.annualreviews.org

LITERATURE CITED

1. Forte JG, Soll A. 1989. Cell biology of

hydrochloric acid secretion. See Ref. 153,

pp. 207–28

2. Ito S. 1987. Functional gastric morphology. In Physiology of the Gastrointestinal

Tract, ed. LR Johnson, pp. 817–51. New

York: Raven

3. Forte TM, Machen TE, Forte JG. 1977.

Ultrastructural changes in oxyntic cells

associated with secretory function: a

membrane-recycling hypothesis. Gastroenterology 73:941–55

4. Helander HF. 1981. The cells of the gastric mucosa. Int. Rev. Cytol. 70:217–89

5. Forte JG, Yao X. 1996. The membranerecruitment-and-recycling hypothesis of

gastric HCl secretion. Trends Cell Biol.

6:45–48

6. Pettitt JM, Humphris DC, Barrett SP, Toh

BH, van Driel IR, Gleeson PA. 1995.

Fast freeze-fixation/freeze-substitution

reveals the secretory membranes of the

gastric parietal cell as a network of helically coiled tubule. A new model for pari-

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

etal cell transformation. J. Cell Sci. 108:

1127–41

Berglindh T, Dibona DR, Ito S, Sachs

G. 1980. Probes of parietal cell function.

Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 238:G165–G76

Pettitt JM, van Driel IR, Toh BH, Gleeson

PA. 1996. From coiled tubules to a secretory canaliculus: a new model for membrane transformation and acid secretion

by gastric parietal cells. Trends Cell Biol.

6:49–52

Duman JG, Pathak NJ, Ladinsky MS,

McDonald KL, Forte JG. 2002. Threedimensional reconstruction of cytoplasmic membrane networks in parietal cells.

J. Cell Sci. 115:1251–58

Berglindh T, Öbrink KJ. 1976. A method

for preparing isolated glands from the rabbit gastric mucosa. Acta Physiol. Scand.

96:150–59

Chew CS. 1994. Parietal cell culture: new

models and directions. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 56:445–61

14 Jan 2003

13:55

Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003.65:103-131. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org

Access provided by Massey University on 08/02/15. For personal use only.

124

AR

YAO

AR177-PH65-05.tex

¥

AR177-PH65-05.SGM

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: fhd

FORTE

12. Chew CS, Ljungstrom M, Smolka A,

Brown MR. 1989. Primary culture of secretagogue-responsive parietal cells from

rabbit gastric mucosa. Am. J. Physiol.

Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 256:G254–

G63

13. Prinz C, Zanner R, Gerhard M, Mahr S,

Neumayer N, et al. 1999. The mechanism of histamine secretion from gastric

enterochromaffin-like cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 277:C845–C55

14. Roth JA, Ivy AC. 1944. The synergistic

effect of caffeine upon histamine in relation to gastric secretion. Am. J. Physiol.

142:107–13

15. Chew CS, Hersey SJ, Sachs G, Berglindh

T. 1980. Histamine responsiveness of isolated gastric glands. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 238:G312–G20

16. Chew CS. 1983. Forskolin stimulation of

acid and pepsinogen secretion in isolated