delving into country risk

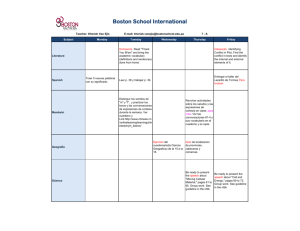

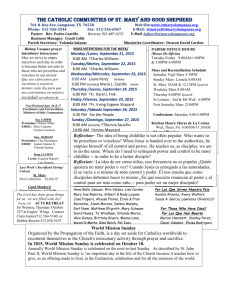

advertisement