THE PERSIAN EMPIRE AND ATHENS

advertisement

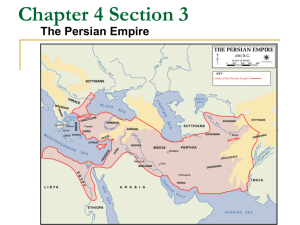

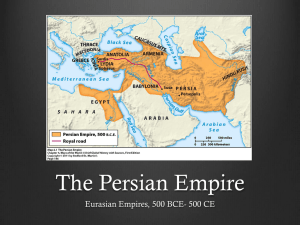

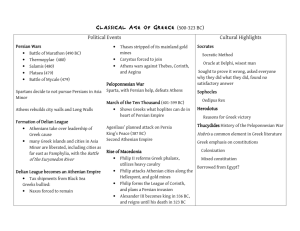

THE PERSIAN EMPIRE AND ATHENS The Athenians entered the fifth century BC with a new sense of civic pride, a growing consciousness of their power, and a workable democratic constitution. As Herodotus put it: “Thus Athens went from strength to strength, and proved, if proof were needed, how noble a thing freedom is.” They would need all the pride and power they could muster for the coming confrontation with the mighty Persian Empire. The Persian Empire The Persians, like the Greeks, were an Indo­European people who came from the north. By the time of the Greek Dark Age, they had settled the Iranian plateau. There is a consensus that the Persian tribes originated in the grasslands that lay between the Steppes of Russian and the settled agricultural lands of the Fertile Crescent. As the historian William McNeill put it: “In this setting, not long before 1700BC, a critically important fusion of civilized technique with barbarian prowess seems to have occurred.” (Keegan, p. 160) This was the perfection of both horse breeding and the technical problem of using horses to pull a deadly mobile weapon of war: the chariot. Eventually the Persians took the next step and learned to fight on horseback. In other words, the Persians, like later Steppe peoples such as the Huns and the Mongols, applied the lessons they learned as herders to the problem of fighting. Their weapon of choice, the composite bow, enabled them to fight on horseback, killing their foes from a safe distance. Their boast was that when the Persians shoot their arrows, they would hide the sun. The following Roman description of the way the Huns fought applies as well to the Persian tactics: “In battle they swoop upon the enemy, uttering frightful yells. When opposed they disperse, only to return with the same speed, smashing and overturning everything in their path. There is nothing to equal the skill with which—from prodigious distances—they discharge their arrows, which are tipped with murderous iron.” (Keegan, p. 162) All Near Eastern empires were won by force and the Persians were no exception to this rule. Around a nucleus of chariots, Cyrus organized the Medes and Persians—the two principal tribal groups of his kingdom—into an effective cavalry force of horse­ archers. No Near Eastern people could withstand them. According to Herodotus, who admired the Persians for their personal morality if not their empire, the young men of Persia were "taught three things only: to ride a horse, to use the bow, and to tell the truth." (Herodotus, I, 136) By the time the Athenians and Spartans were creating their unique political systems and creating workable alternatives to monarchy, the Persians were unifying their various tribes, and setting up a monarchy on the grand scale. From the time of Cyrus the Great (559­530 BC), until the conquest of Persia by Alexander, one family, the Achaemenids, ruled the Near East as the "Great King" of the Persian Empire. The Persians conquered the Babylonians, the Assyrians, Palestine, Syria and finally Egypt. According to the Old Testament, (Esther 1:1) the Persians held sway “from India to Ethiopia, one hundred and twenty­seven provinces.” Cyrus was a great conqueror but he 2 was also remembered by many of the peoples of the Near East as a benevolent and humane king who respected the religious traditions of the incredibly diverse group of nations and peoples under Persian rule. Earlier Near Eastern empires like the Assyrian, had ruled by terror deporting entire populations, sacking cities, and enslaving or massacring prisoners. Cyrus won his empire by force, but he kept it by a sound policy of toleration for all religions and ethnic groups. It was as part of this policy that Cyrus allowed the Jewish people to return to Judea from the Babylonian Captivity and rebuild the Temple at Jerusalem. The prophet Isaiah declared: Thus says Jehovah to his anointed, to Cyrus whom he grasps by his right hand, that he might subdue nations before him, and ungird the loins of kings, To open doors before him, that gates shall not be closed: "I will go before you and I will level the roads, and I will hew bars of iron to pieces, I will deliver buried treasures to you, and hidden riches. (Isaiah II, 45:1­3) Beyond this outward benevolence there can be detected a grand design. Cyrus was prepared to respect national sensibilities only to the extent that they served to weld together a new empire greater even that its Babylonian and Assyrian predecessors. Cyrus was in the empire business, and that boils down to a military elite extracting the surplus from millions of hardworking farmers and living off the fat of the land. But, as we shall see, the Persians were probably more benevolent than the average run of Near Eastern empire builders. (Hallo, p. 148) The Persians remembered Cyrus as the father of their country and even the Greek historians remembered him with reverence. The Nature of Near Eastern Empires The Persian Empire unified the entire Near East politically, but only to a certain point. The variety of languages, customs, laws, and religions so vast as to make the differences between Greek states like Athens and Sparta seem insignificant. Cyrus and his successors allowed the people of the empire to live according to local custom and law, so that the ordinary subject knew only that he or she was being governed well, or at least the way things had always been done. Each province or Satrapy, was obliged to pay an annual tribute. The king, as commander in chief, defended his subjects from intruders and in return they paid him taxes. There was no uniform administration because none was needed. The Persians worked to improve the general prosperity by building roads and creating a postal system staffed by royal messengers on horseback. Herodotus reported that “Neither rain, nor snow, nor sleet, nor hail stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” (Herodotus, 8, 98). Like all empires of the ancient Near East, the Persians were utterly merciless in the suppression of revolts against their rule. King Darius, who later would invade Greece, built a great monument to himself carved out of a rock face at Behistun. The text was given in Sanskrit, Babylonian, and Greek and is important largely because it enabled later linguists to decipher Cuneiform. The political message Darius shared with his subjects was clear as well: all who opposed the power of the Persian “Great King” could expect a terrible fate. The monument tells of King Darius' successes in crushing revolts in the 3 empire. The relief portrait shows King Darius facing a line of nine conquered rebels, their necks linked by a length of rope and their hands tied behind their backs. Over the head of the captive floats the winged figure of the Persian god Ahura­Mazda. The text tells of the bloody deaths of the captured rebels including this passage: “Afterwards I cut off both his nose and ears, and put out one eye; he was kept bound at my palace entrance; all the people saw him. Afterwards I impaled him.” (Fine, p. 260) Greek scholars and Hebrew prophets might admire the generosity of Cyrus and everyone feared Persian power, yet the Persians personified what the Greeks meant by the word barbarian. The “Great King” of Persia was an autocrat who extracted tribute, exploited the labor of his subjects for building projects, and forced subject peoples to serve in his army. The king claimed the right of life and death over his subjects, who knelt or even prostrated themselves in his presence. In his play The Persians, the Greek playwright Aeschylus suggested the essential difference between the Greeks and the Persians. The Persian queen asks about the Athenians: “Who commands them? Who is shepherd of their host?” The Chorus responds: “They are slave to none, nor are they subject.” The Greeks pitied the subjects of the Persian king, considering them his slaves. For their part, the Persians were not impressed with the Greeks. There is a story that King Cyrus once received a Spartan envoy that warned him not to harm the Greek cities of Ionia. Cyrus, taken aback, asked whom the Spartans were. After receiving an explanation, Cyrus told the Spartans, “I have never yet been afraid of men who have a special meeting place in the center of their city, where they swear this and than and cheat one another. Such people, if I have anything to do with it, will not have merely the troubles of the Ionians to chatter about, but their own.” (Herodotus, p. 103) Clearly the Greeks and Persians neither understood, nor admired one another. The enmity between the Greeks and Persians had another purely political source as well. The Greeks who lived under Persian control regarded them as a foreign elite whose rule was essentially exploitive. Like the other great monarchies that came before, the Persian Empire contained the seeds of its own destruction. Empires came and went in the Ancient Near East because so far as the ordinary subject was concerned, one despot was the same as the next; one foreign tribe was as arrogant and predatory as another. The Persian Empire shared the same political brittleness as any other empire based on military force. Why should the inhabitants of the Persian Empire care what happened to the Great King? A thousand years later the tired, oppressed “citizens” of the Roman Empire asked themselves why should we care whether Rome fell? The same attitude was widespread in the Soviet Union during the 1980s and 1990s. When Hernan Cortes came to Mexico in 1519, he encountered many among the subject tribes of the Emperor Montezuma who preferred Spanish tyranny to Aztec tyranny. (Landes, pp. 39­40) The Greeks who liked to see themselves as the defenders of freedom against Asian tyranny, perceived this indifference as their secret weapon. As the physician Hippocrates wrote: Where there are kings, there must be the greatest cowards. For men’s souls are enslaved and refuse to run risks readily and recklessly to crease the power of somebody else. But independent people, taking risks on their own behalf and not on behalf of others, are willing and eager to go into danger, for they themselves enjoy the fruits of victory. (Landes, p. 40) 4 The Ionian Revolt The stage was set for a collision between the Greeks and the Persians Empire was set in 547 BC, when the Greek cities of Ionia, the west coast of Asia Minor, came under Persian rule. The Persian ruled Ionia with their trademark benevolence, at least at first. They tended to support tyrants in the Ionian cities or small oligarchies, they demanded taxes, and they followed the custom of recruiting or drafting native troops to serve in their army. Greeks fought in the Persian army that invaded Egypt and campaigned in other areas of the Persian Empire. From the beginning, the Ionian Greeks resented Persian control and they reacted against it by waiting for the first opportunity to regain their independence. Violence might never have broken out if it had not been for the schemes of Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus. Aristagoras resigned his tyranny and became something of a crusader for freedom among the Greek cities. He even toured mainland Greece, carrying a bronze map of the world to show the Greeks the danger of Persia, in an attempt to preach a pan­Hellenic war of liberation against the Persians At Sparta, he told King Cleomenes that the Spartans could beat the Persians in battle, “they use neither shields nor spears, so easy are they for the beating.” (Herodotus, p. 379) When Aristagoras offered the sum of fifty talents of gold for Spartan assistance, the King's daughter spoke up and said, “Father this stranger will corrupt you.” The Spartan king sent Aristagoras away with these words: ‘Leave Sparta before the sun sets! There is no argument of such eloquence that you can use on the Spartans if you want to bring them three months' journey from the sea.’ (Herodotus, 5:50) Aristagoras had more success in Athens. He was allowed to address the assembly. The Athenians voted to send twenty ships to assist the Ionians. Herodotus remarked that this episode shows it is easier to deceive many than one, for Aristagoras succeeded in convincing 30,000 Athenians where he failed with King Cleomenes of Sparta. Incidentally, this is the only historical reference we have for the number of citizens in Athens in 500 BC. Herodotus noted, “The sailing of these ships were the beginning of evils both for the Hellenes and the barbarians.” (Ibid, p. 379) It is little difficult to imagine why the Athenians would dare to challenge the Persians; the most likely source of Athenian confidence was their undoubted superiority at naval warfare. In fact, the Greeks were just beginning to understand the potential of a naval strategy for both offensive and defensive military operations. As Thucydides put it: “[The size of Greek fleets] did not prevent their being an element of the greatest power to those who cultivated them, alike in revenue and dominion.” (Thucydides, I, 15) Ultimately, as we shall see, it would be the Athenians under Themistocles who mastered naval strategy to the benefit of all Greeks and the detriment of the Persian empire. The standard warship of the Greek world was the Trireme with 180 oarsmen arranged in three banks on each side of the vessel. An Athenian Trireme was 135 feet long, 10­13 feet in width, and drew about four feet of water. Besides the rowers, each ship carried 17 crewmen (captain, flutist to keep time for the rowers, and fifteen deckhands), and fourteen marines (ten hoplites and four archers). The ship was steered by two steering oars aft. It had a single mast and sail that was normally lowered before battle. The principal weapon was a bronze ram in the bow. These galleys were too fragile to face heavy weather and too small to carry supplies so they were usually beached at 5 night so the crew could eat and sleep ashore. The Athenians did not use slaves to row their Triremes; instead the rowers were professionals sailors recruited from the ranks of the desperately poor. The Athenian aristocrats called them "the naval mob." The Persians soon crushed the Ionian revolt, but the Athenians did earn the special anger of King Darius by their attack and sack of the city of Sardis, the local Persian provincial capital. Persian vengeance was swift and bloody. In 494, the Persians took the city of Miletus. The fall of Miletus and the harsh treatment given its citizens clearly shocked the Athenians. One poet produced a play for the drama festival at Athens that year called the Capture of Miletus. Herodotus related that “the audience in the theater burst into tears, and the author was fined a thousand drachmas for reminding them of a disaster which touched them so closely.” (Herodotus, 6:21) Darius was so angry at the Athenians for their role in the burning of Sardis, he ordered a slave to stand behind him “and repeat three times whenever serving dinner, 'Master remember the Athenians.’” (H. 5: 105) The Marathon Campaign, 490 B.C. The Persians determined to punish Athens for their assistance to the Ionians and to intimidate the rest of mainland Greece. Envoys were sent to the Greek states to demand "earth and water" which were the traditional signs of submission. The Spartans threw the envoys into a well, telling them to take all the earth and water they wanted; many other Greeks submitted. Athens was not asked for it was to be punished. In 490 BC, a large Persian fleet with an army of 25,000 sailed across the Aegean towards Athens. The Persians also brought along the aged Hippias, the former tyrant of Athens who they planned to install as ruler once again. On the advice of Hippias, the Persians decided to land at Marathon, the area of Attica where the holdings of Peisistratus were located. The Athenians asked for aid from Sparta. The Spartans agreed to send an army to help, but insisted they could only leave at the end of a month­long religious festival. The Athenians would have to fight alone except for a force of one thousand hoplites from the small state of Plataea. The Athenian followed the progress of the Persian fleet and marched to meet them. The Athenian army was about 11,000 strong counting the hoplites from Plataea and they camped on the hills above the bay at Marathon to wait on the Spartans and attack the Persians. In the event, the Persians arrived first. Miltiades, the Athenian commander, knew the Persian way of fighting well and he adopted an aggressive strategy to take advantage of the Athenian armored hoplites. He thinned out the center of the phalanx and deepened the wings. He reasoned that the battle to come would tempt the Persians to attack the Greek center and thus force the wings of the phalanx to slam shut like the jaws of a bear trap. Forming up in the hills, the Athenian phalanx of hoplite militiamen ran a full mile in armor to get at the Persians before they could unload their horses and form up their trademark cavalry. Attacking on the run also meant that the phalanx was less vulnerable to the deadly Persian archers. It is best to read about the battle in the wonderful account of Herodotus: The dispositions made, and the preliminary sacrifice promising success, the word was given to move, and the Athenians advanced at a run towards the enemy, not less than a mile away. The Persians, seeing the attack developing at the double, 6 prepared to meet it, thinking it suicidal madness for the Athenians to risk an assault with so small a force­­rushing in with no support from either cavalry or archers. Well that was what they imagined; nevertheless, the Athenians came on, closed with the enemy all along the line, and fought in a way not to be forgotten. They were the first Greeks, so far as I know, to charge at a run, and the first to look without flinching at Persian dress and the men who wore it; for until that day came, no Greek could hear even the word Persian without terror. (Herodotus, 6:115) Although outnumbered, the Greeks held all the advantages. The fight was long and grim, especially in the center. But the Greeks had superior armor and longer spears. The Greeks victory at Marathon demonstrated the superiority of the hoplite phalanx, especially in a situation where cavalry and missiles could not be brought to bear. The geography of Greece did not favor the Persian tactics of mounted archers keeping their distance while shooting clouds of arrows at the enemy. Greece lacked the open plains where such armies could operate comfortably. Nor did Greece have the broad grasslands where a cavalry force could allow its horses to graze. But Marathon was not merely a matter of armor and spears, nor of free men versus slaves, as Herodotus explained the outcome. The Persians preferred to fight at a distance, they made use of missile weapons (slings and bows), and they generally only closed to arm's length when victory seemed assured. The Greek way of fighting stressed short, violent, intense conflict with formations of men closing to spear length of one another "to end the whole business quickly and efficiently." Somehow Greek psychology encouraged a harsher mode of war. The Greeks fought like madmen, or at least men possessed. The Persians thought a “destructive madness” had infected the Greek army. As Victor Hanson, the historian of phalanx warfare put it: “Surely, as the outnumbered Greek hoplites crashed into their lines, the Persians must have at last understood that these men worshipped not only the god Apollo, but the wild, irrational Dionysius as well.” (Keegan, p. 253) Gradually the Persians were forced back towards their ships until their lines collapsed and ran. Many were drowned and many more cut down from behind. The Athenians were not content to allow the enemy to retreat but pursued them into the surf and tried to board and seize their ships. “It was in this phase of the struggle,” wrote Herodotus, “that the archon Callimachus was killed, fighting bravely, Cynegirus, too, the son of Euphorion, had his hand cut off with an ax as he was getting hold of a ship's stern, and so lost his life with many other well­known Athenians.” (Herodotus, 6:115) The next morning, the Spartan army arrived, and to their bitter disappointment, they discovered that the Athenians had won the battle without their help. The Athenians lost 192 citizens and an unknown number of Plataeans and slaves. Aeschylus left behind an epitaph that made no mention of the seventy great tragedies he wrote for the Athenian theater, but referred only to his military service: Under this monument lies Aeschylus the Athenian Euphorion's son, who died in the wheatlands of Gela The grove of Marathon, with its glories, can speak of his valor in battle The longhaired Persian remembers and can speak of it too. (Aesch. Vita ) 7 His brother Cynegirus was the unfortunate man who lost his arm hanging on to the Persian ship. Many pious citizens claimed that the gods themselves—including Herakles, Athena, and Theseus—had fought alongside the Athenian hoplites during the battle, as the Greek gods had done at Troy. It is probably politically incorrect to teach the story of Marathon today the way it has been taught for centuries: as the triumph of free Greeks over enslaved Asian servants of a tyrant. It was not a simple battle of good versus evil. But the Greek cities with their diverse constitutions and relatively free societies did represent something new and different in the ancient world. Herodotus drew the conclusion that Marathon was the ultimate justification for the democratic system that Athens had recently adopted. In a celebrated passage he linked a democratic constitution with military power: Now Athens grew more powerful. And there is not one but several proofs everywhere that equality before the law is an excellent thing. As long as the Athenians were ruled by tyrants they were no better warriors than their neighbors, but once they got rid of the tyrants, they became the best of all by a long shot. This shows that while they were oppressed they were willing cowards, like slaves working for a master, but when they became free each man was eager to achieve honor for himself. (Herodotus, 5. 78) The Greek­Persian Rivalry The Greeks did not appear to their contemporaries as a puny and inconsequential people. By the beginning of the sixth century BC the Greek commercial network was potentially as powerful as any other force in the Mediterranean, even if it lacked a single political center or a unified economic purpose. By the way, that was precisely how King Cyrus viewed the Greeks: as wealthy businessmen who also could be a formidable military opponent. It might even be argued that it was the Greeks who pressed the Persians into war and continued the offensive long after the Persians had sought to withdraw from the contest for control of the Aegean and Black seas. Nor was the Greek Offensive limited to the eastern Mediterranean. At about the same time that the Ionian Greeks, supported by mainland cities such as Athens, decided to rebel against their Persian overlords in the east, the western Greeks on Sicily, under the leadership of Syracuse, came into conflict with the Carthaginians and Etruscans. The Greeks almost succeeded in uniting the Mediterranean world in a single great system, as the Romans actually succeeded in doing four centuries later. Their failure was more a result of flaws basic to Greek political values than of the strength and inventiveness of their enemies.