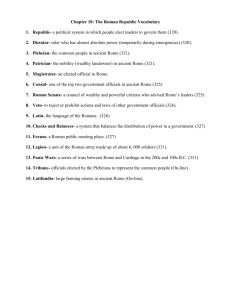

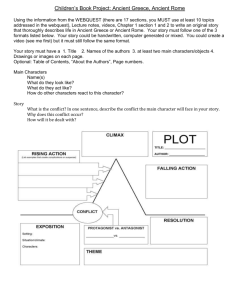

Ancient Rome - Oxford University Press

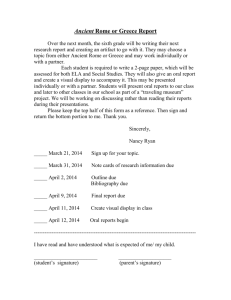

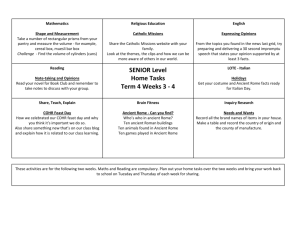

advertisement