Living in the Kampungs: A Firsthand Account of Experiences in

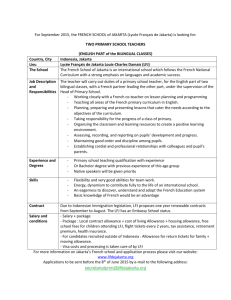

advertisement

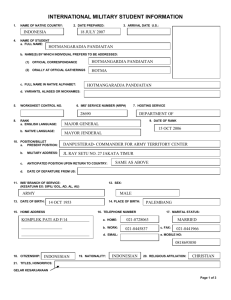

Living in the Kampungs FORUM. Vol.7. ▌ Living in the Kampungs: A Firsthand Account of Experiences in Jakarta’s Kampungs Antony Sihombing University of Indonesia, Indonesia; The University of Melbourne, Australia Keywords: Kampungs, Kota, Jakarta Abstract In this paper I describe my experiences of living in five different kampungs in Jakarta, through a narrative of my lived experiences there. This use of a chronological order incidentally also describes how I climbed the socio-economic ladder from the first poor kampung in Menteng Atas to the middle class kampung Pondok Labu, and how I related to those around me in kampungs at different times, places, and stages. The account also suggests, by implication, the ways that others have risen socio-economically through the ‘ladder’ of the kampungs. I also relate my experiences of surprise and shock when I first lived in a kampung, through my processes of adaptation for living in different kampungs in Jakarta. Throughout this narrative there are two underlying questions. First, how are community values and practices (rukun, gotong royong (mutual self-help) etc.) actually manifested in the face of either internal or external threats, conflicts or surprises? And how might these values and practices underlie a production of space that might be alternative to (or in conflict with) that of kota and the formal sector? interpretation of the experiential social. He pointed out that: Introduction ‘Neighbours are more valuable, special and important than relatives who live in other places.’ This traditional phrase is well known among Indonesians. It describes the concept of relationships among people in kampungs1. The research method is to recollect and record my own lived experiences in five different kampungs at different times, especially my relationships with my neighbours. This paper reports the results of this process. To narrow this gap, the sociologists have to devise a methodology that will enable them to take into account the inner perspectives as well as the outer perspective of the subjects under investigation. This is what qualitative methodology does (Filstead 1970:6). Lynch (1996:5) pointed out that a distinctive and legible environment offers security and heightens the potential depth and intensity of human experience. In this research, kampungs are part of the urban environment. To obtain some insight into the distinctiveness, clarity and legibility of people’s (kampung dwellers’) experiences (Lynch 1996), I will use an inner mode of investigation. Lefebvre (1991) discussed how lived experiences can be investigated through ‘lived, conceived, and perceived’ experiences of everyday life. He argued (1991:39) for an understanding of “the space as directly lived through its associated images and symbols, and hence the space of ‘inhabitants’ and ‘users’”. The ‘inner perception’ of kampung life can be investigated in part through one’s own lived experiences in different kampungs at different times or through people’s own descriptions of their experiences, practices and beliefs, as will be explained shortly. The inner perspective assumes that understanding can only be achieved by actively participating in the life of the observed and gaining insight by means of introspection (Bruyn, 1963:224-35). From my own lived experiences I have perceived kampung life from inside. Others’ own accounts give further stories that might complement (or indeed contradict) my own. This gives the people who live Research Method: Inner Perception The research will focus on the investigation of kampung dwellers’ experiences in their kampungs, and how they perceive kampungs as a part of kota2 Jakarta, to understand the characteristics of kampung itself. In social research, there are two broad methodological perspectives: the outer perspective and the inner perspective (Bruyn 1966:23-5; Filstead 1970:4). Filstead (1970) discussed the concerns of sociologists about the gap between theoretical, methodological, and conceptual elements, and the 1 Kampung is the traditional, spontaneous, fine-grain, and diverse form of indigenous urban settlement in Indonesia which has grown locally, organically and incrementally over many years without planning guidance or regulations, building codes or the centralized and coordinated provision of services. 2 In Indonesia, kota has three common meanings: the original meaning is negara (nation or government); it is also the name of an area in the city centre or downtown Jakarta (China Town); and the third meaning is urban, city or town. I use a fourth understanding of kota in this research, which can be understood as formal, regulated, and planned city. In the second of these meanings it is spelt with a capital ‘K’, as Kota, while in the others with lower case letter ‘k’, as kota. 15 Living in the Kampungs ▌FORUM. Vol.7. in kampungs a way of expressing their own ‘inner perceptions’ of their lives. The method, based on a form of reflective self-observation helped me to understand what kampungs are. Menteng Surprises and Shocks in Menteng Kampungs (1978-1986) Menteng is an elite settlement located in a prime area in Central Jakarta. Menteng is also known as the first ‘garden city’ or kota taman (Heuken and Pamungkas, 1997), with Surapati Square (figure 1) as the centre of this area. Menteng is the highest-income settlement in Jakarta, and has the highest cost housing. From the beginning, this place became a prime settlement for elites: Dutch colonial officers, public officers, rich families, the nobility and expatriates. Today, Menteng is the place where many very important people live, such as the President and Vice President, ministers, ambassadors, government executives or officers (pejabat tinggi negara), owners and managers of the conglomerates. In 1908, Menteng was established by the Dutch colonial governor, General-Governor A. S. Carpentier Alting, and continued by J. B. van Heutsz a year later (Kompas, 3.8.2000). Menteng was the extension to the south of Batavia city.3 At present, because of its history, Jakarta’s government has decided to declare Menteng a conservation area, as indicated in the Master Plan of Jakarta 2010 (Pemprov, DKI Jakarta 1999). Thus, Menteng is one of the most important places in Jakarta, geographically and socio-economically. Monas Suropati Square Figure 1. The Menteng Area: DKI Jakarta (key plan); Menteng area and surroundings at present. (Source: Pemprov. DKI Jakarta 1999; Holthorf 1998) However, there are other ‘Mentengs’ surrounding Menteng across the Malang River to the south: Menteng Atas, Menteng Wadas, Menteng Sawah, Menteng Ratna, and Menteng Pulo (figure 2). In Menteng Pulo is also located a large cemetery in the centre of Jakarta. All of these are recognized as kampungs. Mangga I lived in several different kampungs surrounding Menteng, when I first moved to Jakarta, such as in kampung Menteng Atas for three years from 1978 to 1981, kampung Pasar Manggis for two years (1981–1983), and kampung Gang Edi-Halimun for another three years (1983–1986). On account of similarity of my experience in these Menteng kampungs, I will focus the discussion on kampung Menteng Atas. Pasar Gang Menteng Figure 2. Recollected map of Menteng kampungs (Source: sketch by author) 3 Batavia is old Jakarta in Dutch colonial era (1619-1942). 16 Living in the Kampungs FORUM. Vol.7. ▌ household basic needs; one in the middle which sold fresh food (in the morning and afternoon only); and another at the right corner which sold daily needs. Behind these tenement houses, there were home industries producing tahu (traditional tofu) and tempe (traditional soybean cake); and a small open space, a place for people preparing mie bakso (meatball and noodle soup) on movable shops before selling them to the residents in the kampung and the surrounding areas even up to Menteng, Monas and elsewhere. Menteng Atas Menteng Atas was the first kampung where I lived after moving to Jakarta from Sibolga—a small town on the west coast of the Province of North Sumatera—at the end of 1977. I moved to Jakarta to continue my studies at the University of Indonesia, which at the time was located around two km from this kampung. Because of its location, it seemed to me that this kampung was a great place, close to the city centre, in particular to my university, in the middle of Jakarta and close to Monas4 and Independence Square. However, at the beginning of my experience of living here, a question arose in my mind: is this settlement really part of Jakarta city? I found the differences in experiences between Sibolga and Jakarta surprising. I had never thought before that Jakarta might be a kampung as well. Even though this kampung was adjacent to Menteng, there was no electricity distribution in it at that time. So for two years, I lived here without any electric light. It seemed dark and scary for a new resident like me, especially in the evenings. At the end of 1980, the inhabitants were surprised when our kampung was connected to the electricity supply, and we celebrated electric light for the first time. Figure 3. Recollected map of my neighbourhood in Menteng Atas (Source: sketch by author) As a result of its low socio-economic class and limited area, most of the public facilities and infrastructure in this kampung were inadequate. Right in front of my house there was a MCK5 and a small open space, three metres wide and four metres long. This small open space was a mediating space between the houses, the MCK and the langgar (small local mosque), which was located next to it. The MCK is very important for kampungs because some houses do not have their own toilet. For some people in this kampung a house is just a place for having a rest or sleep in the evening. Social interaction among family members or neighbours takes place on the lane in front of their houses, in front of warungs6 or other small open spaces during the day. Sanitation in this kampung was also very poor. Septic tanks were located next to the artesian wells used by people to get water for drinking and cooking. The house itself looked like a hallway divided into three parts: living room at the front, two bedrooms in the middle, and service rooms (dining room, kitchen, and toilet) at the rear. Thus there was no ventilation for the bedrooms, except for windows and doors at the two ends. The building had cement floors, brick walls, teakwood ceilings, and a red clay tiled roof. Kampungs look very attractive from above, with their mosaic of red roofs like a beautiful mosaic painting. From a bird’s eye view, almost all roofs in this kampung seemed to be joined one house to another. Thus, it is easy to distinguish between houses, open spaces (if any), waterways (if any), lanes or streets (figure 4). The small open space in front of my house was also a very lively space, with children playing and adults relaxing, talking and having fun. The lane, one and a half metres wide, was also an important space in my kampung. Thus, although it was used for pedestrians it was also an open space. From morning to evening, this lane was a very bustling place, with people walking through, talking to each other, and children playing, particularly in front of the three warungs, because there were no other adequate open spaces for this activity. I stayed with my relatives in one unit of a one-storey tenement house. These houses were typically three metres wide and eight metres long. The owner of this row lived at the corner between the lane that ran along these houses and the main street to the area (figure 3). In each row there were ten units, and I lived in the middle. In this row, there were three warungs: one at the left corner which sold 4 Monas stands for Monumen Nasional or National Monument. It stands on the centre of the Independence Square. The social, cultural, and economic backgrounds of the people who lived along the lane where I lived were diverse. We were from different ethnic groups (Javanese, Sundanese, Betawi, Batak, and Chinese); from various professional backgrounds (teachers, police, traders in 5 MCK stands for mandi, cuci and kakus (or public bath, washing, toilet). 6 Warung is a traditional local shop/kiosk in a kampung, which usually provides the daily needs of people in the kampung. Off-street warungs refers to warungs in kampungs, which usually have no streets or, in other words, these kampungs are accessed by lanes only. 17 Living in the Kampungs ▌FORUM. Vol.7. association), pak Haji (Islamic leaders),8 civil servants (pegawai negeri), teachers, and people with higher incomes. Our RT’s headman was a teacher in an elementary public school who ran a warung at the left corner of our row houses. The owner of the detached row houses where we lived was pak Haji. He lived in the biggest house in this neighbourhood at the right corner, with his extended family: his children, his children’s family, and his relatives from desas (in Central Java) who were working for him to produce tahu (traditional tofu) and tempe (traditional soybean cake). He also operated the biggest and most complete warung in this kampung. markets, food makers, owners of warungs, students, and operators of home industries); and of different ages (children, young families, and old people); and different religions. Most of us were Moslems, with some Christians and Buddhists. We had regular monthly meetings in our community led by pak RT, which took place in his house, in pak Haji’s house, or in the RW post. The main topic of our meeting was neighbourhood rukun,9 gotong-royong (mutual selfhelp), security, and other social and cultural events (such as tujuh belas agustusan).10 To encourage neighbourhood residents to come to this meeting, it was usually followed by arisan.11 Figure 4. Roofs of Kampungs in Jakarta (Source: Archnet in http://archnet.org/library/sites/onesites) Every kampung always has its own Hansip (Pertahanan Sipil or civil defense), which is hired by the residents to maintain security. However, this is not enough to guard all For daily shopping, residents just walked, because there was a Pasar (traditional market) Ratna around one hundred metres away and there were many warungs nearby. Usually, all local pasars like this are also called pasar basah (wet or fresh market) for two reasons: pasar for fresh food, so they need much water, instead of refrigerators, to keep their vegetables, fish, fruit, and meat fresh; and the pasar is certainly wet on account of this water. As a consequence of bad sanitation, it is not unusual for pasars to bring bad smells into the area and its surrounding settlement. In the evening, there was an evening market along Jalan Kawi, 150 metres from my place to the north. There were always people selling and buying their basic needs such as clothes, kitchen equipment, school materials, and many kinds of food. Sellers placed them on a mat laid down on the path, even on the edge of the street, leaving room for only one car to pass down the street. representatives of government. In the present reform era, people expect that RT and RW (both leadership and organization) are fully their representatives. 8 Pak comes from bapak, meaning Sir, Mr., or someone who is respected by others because he is older, or more powerful socially, culturally or financially. Haji is someone who has done the fifth rukun of Islam, the pilgrimage to Mecca. 9 According to Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia (The Great Dictionary of Indonesian Language 1988), there are three meanings of rukun. The first is rukun as a basis, foundation, or principle, e.g. ‘rukun Islam’ (Islamic principles or pillars). The second is rukun understood as ‘good’ and ‘peace’ in connection with relationships. It also means ‘one mind’ or ‘one interest’, or unanimous. The third is rukun as association or organization based on mutual self-help and relationships, e.g.: rukun tani (farmers organization); rukun tetangga (people, community or neighbourhood organization or institution); and rukun kampung or rukun warga (kampung or community organization in one sub-district). In the discussion in this section, the second and the third of these meanings are the most useful for explaining communities in kampungs. 10 The words tujuh belas agustusan come from 17th August, our independence day. For a week around this day people in kampungs celebrate Indonesia’s Independence Day, more than the people in kota. These celebrations include many attractions or competitions for children, adults, women and men. And usually, on the Saturday evening of this week, each community or a group of communities hold a RW (neighbourhood) performance or cultural night. Tujuh belas agustusan is mutual self-help activities: ‘from people’ (they create their own ideas and collect money from the residents to perform these activities); ‘by people’ (they are the committee members); and ‘for people’ (these attractions are just for residents in the community or neighbourhood). Those who worked outside the kampung usually rode bicycles or motor bikes, or caught public transport. The closest bus stops were about 150 metres to the north and to the west. During the three years I lived in this kampung, I never experienced a flood in the area. I never faced any difficulties in catching public transport to get to my university. Sometimes I got to the university by walking or cycling. 11 Arisan is the traditional and mutual self-help banking system in communities, neighbourhoods or small groups of people to help the members to get a large amount of money to use in a particular way for a large household item. For example, in one community there are 20 households in the arisan group, and each member puts in Rp. 20,000 monthly, so they will get Rp. 400,000 when their turn comes. The member can get one turn every twenty months through the draw at every monthly meeting. Thus, they can buy extra household needs such as electronics, clothes, and bikes. The society leaders in our kampung were pak RT (head of community association),7 pak RW (head of neighbourhood 7 RT stands for Rukun tetangga (community), which has a population of 250–300 people. RW stands for Rukun warga (neighbourhood), which consists of about ten RTs. Even though the heads of both RT and RW are elected by the people, during the Suharto regime they were also 18 Living in the Kampungs FORUM. Vol.7. ▌ Centre (Gelanggang Mahasiswa Kuningan) to the south of Menteng Atas. This Student Sports Centre also changed recently, before the Indonesian crisis, to become a mixeduse area of apartments (eighteen towers), private sports centre, offices and commercial buildings such as an international mega-shopping centre and food centre (a collaboration between a French company and a local conglomerate). Now this sports centre belongs to and is managed by the conglomerate that owns the whole area. areas in the kampung. Therefore, to guard the kampung, RTs or RWs have a roster of adult male residents drawn up for the night neighbourhood watch. During the monthly meetings pak RT discusses the neighbourhood security and comfort and evaluates the night neighbourhood watch. A person’s watch duty could be performed by another resident if he had a strong reason (such as sickness, overnight job in his office, being outside the city). But he should pay with cigarettes, coffee or tea, and snacks for the replacement guards at supper time. This attractive kampung has now gone. It was demolished in the middle of the 1990s to build those eighteen towers of apartments (each over twenty floors high) and a CBD. Hari Raya Idul Fitrie, the great day of Islamic celebration, is an important day in the kampung, because most of the residents are Moslems. In the morning of this day, Moslems go to the Mosque or to a large ground or field outside the kampung, where they pray together and celebrate this great day. When they return, everybody (from all religious backgrounds) in the kampung comes out from their home to the lane or street to give their best wishes to the Moslems and apologize to each other for their previous bad habits. The Moslem residents send meals to their neighbours to share their joyfulness, and conversely, on the other celebrations of other religions (such as Christmas Day for Christians, Chinese New Year for Buddhists) they also do the same. Conflicts in Manggarai (1986-1992) After I married in 1986, we (my family, my brother and sister) moved to Manggarai to live in a bigger house, even though still in an off-street kampung. This house was located in a lane about forty metres to the south from the local street of Jalan Swadaya II. The main street is Jalan Saharjo, about 70 metres to the west of my house through another lane (figures 2 and 5). On the day we moved there I transported my household goods in several trips by car. On the first trip I had a problem from a group of youths in this kampung. They would not allow me to park my car on the street close to the lane where we lived. They kept standing on the street car park where I wanted to park my car, and I had to push them away by force. One of them fell down into the drain and we nearly fought each other. Pak Haji, who lives in this street close to this place came to separate us, and asked us to go in peace. From that moment on the kampung residents recognized us as members of their society. On the next trip, we were assisted by some of my new neighbours, even though we had just met each other. They came to help us to carry up all our stuff from my car to my house. This was our first experience of gotong-royong in this kampung. This happened because all the residents in this kampung respected pak Haji. The most important facilities in this kampung are pasar, warung, masjid, langgar, and MCK. Warungs have many functions in kampung living, both social and economic. Even though Jakarta is a modern, global capital city, its trading system of warungs in kampungs is still traditional. Almost every warung in kampung Menteng Atas had a notebook to record the list of residents who had been given credit by the warung owners. The residents would pay weekly or fortnightly for informal sector workers and monthly for formal company workers. Another thing that made Menteng Atas an attractive kampung was its accessibility to work places and public transport. People who lived in that kampung had various occupations: government servants (clerks, teachers, administrators, municipal officers etc.), students, suppliers, retailers in traditional markets, and home industries, but most of them were unskilled labourers (informal sector, construction labourers, vendors, servants, etc.). Generally, people who lived in that area served or worked in the Central Business District and Menteng settlement. There was a strong connection between kampung Menteng Atas, Menteng, and the Central Business District. Right across the lane from our house was the pak RW. He was also pak Haji, and worked as an amateur photographer, and together with his wife also in their own shop, selling daily needs and fresh food and also running a photographic studio. Our pak RT lived behind his house in a tiny lane, only half a metre wide. He worked in the Ministry of Defense office as a clerk. Our house was bigger (90 square metre), on one floor, and more comfortable than any I had lived in before, with three bedrooms, living room, dining room, kitchen, two bathrooms, and a place for drying clothes on the roof level. Located on a corner, our house got adequate fresh air through the windows and other ventilators. The biggest problem was that there was no adequate open space, or public-space for playing. People who lived in kampung Menteng Atas actually had a public cemetery on the south named Menteng Pulo, and they often used that to play football or other sports. They also played football on grounds along Jalan Kuningan (one of the main streets linking south to north), when the area was still empty before the new CBDs were developed. However, now there is no public open space or public park along Jalan Kuningan, except a small part of Kuningan Student Sports We were helped in our home by a woman, a domestic servant who was from a desa in Central Java. In kota life style, even when they live in kampungs, most families are supported by at least one domestic servant. As such servants mostly live with their employer. When designing 19 Living in the Kampungs ▌FORUM. Vol.7. socio-economic activities in kampung Manggarai were better than in any other kampung I had previously lived in. houses for middle or higher socio-economic groups the architect always allows for at least one maid’s room. Domestic servants work in the home from morning to evening. Their main jobs are home tasks such as house cleaning, cooking, clothes cleaning, and also shopping for daily needs. The New Urban Kampung of Pondok Labu (1993-2000) In 1993 we moved to Pondok Labu, South Jakarta. The area is on the border between city of Depok (Province of West Java) and DKI Jakarta. Even though our area is in West Java, our address still retains a Jakarta postcode. Many people who live in border areas like this, particularly in the Jabotabek area, still keep their Jakarta citizenship identity card (KTP or Kartu Tanda Penduduk). After our financial situation became more stable, we bought a parcel of land in the South of Jakarta from pak Haji. The reason why we chose this area was because the University of Indonesia, the place where I was teaching, moved to Depok (West Java), about 20 km to the south from Jakarta. The land that we bought actually belonged to members of a big family, and was their tanah adat (traditional land). Before we bought this parcel, pak Haji first asked the approval from his family members (wife, children and grandchildren). When we moved there, this area looked like a desa or rural green settlement. This is the type of settlement that Krauss (in Marcussen, 1990) might call a ‘Peripheral Squatter Settlement’, although in this case there was certainly no squatting. Our settlement was surrounded by a lot of big trees, more than ten metres high, like a tropical forest. This is now changing from a rural settlement to become an urban settlement, and the trees have been replaced by large luxury houses. Although we lived in a bigger house (parcel 1 in figure 6) than ever before, two floors with a total of 160 square metres floor area on 250 square metres of land, our house was the smallest in our neighbourhood. This kampung was also growing up as an elite settlement inhabited by many people from middle to upper socio-economic class: in front of our house is the manager of the biggest shopping centre in Jakarta (parcel 2); across the street from our house is an expatriate French consultant to a big national private company (parcel 3); another neighbour is President Director of the biggest fast food franchise company in Indonesia (parcel 4). The new residents live along the street; however, living in side or off-street kampungs are Betawi people, the indigenous Jakartans, and some Sundanese and Javanese (parcel 5). Figure 5. Recollected map of my neighbourhood in Manggarai (Source: sketch by author) Security in this kampung was not as good as in the other kampungs we had lived in before. The relationship between people here was harmonious (rukun), but this was not so in another neighbouring kampung located behind our kampung. Many crimes were committed in that kampung, such as using drugs and drunkenness, which led to stealing, robbery and youths fighting. Our community was one of the victims of this. While we lived there, many bicycles, motor bikes and even cars were stolen from our neighbourhood. As a result of this, we were not willing to park our car on the street. We parked it in pak Haji’s front yard, which was rented as a private car park; or we parked it in a large rented car park area belonging to the military warehouse, one hundred metres from our house. Our experience of living there is very interesting. Even though many residents moved from the centre of Jakarta and from middle to high socio-economic groups, the traditions of kampung, gotong royong and rukun are still alive there. For example, the indigenous residents usually give us some fruit from the first harvest of their plantations (rambutans, mangos, and durians) in their large back yard gardens. And at the time of Hari Raya Idul Fitrie (Islamic Great Celebration) they still send us special food, which they have prepared for others to become part of the celebration, even those that are not Moslems. Many traditional pasars were found around our neighbourhood. In the morning, there were many temporary morning markets at strategic places such as junctions, open spaces, and on the street. Pasar Minangkabau in Jalan Saharjo was the nearest pasar, about seventy metres from my home. The public transport and 20 Living in the Kampungs FORUM. Vol.7. ▌ a low socio-economic class and the informal sector, they exercise a vast influence on Jakarta. During the one week of this season Jakarta is quiet and there are no traffic jams. Conclusion For new residents or outsiders, kampungs are full of surprises. The biggest surprise is that kampungs truly exist, and constitute the real settlement of Jakarta. The original kampungs are very dense, with small houses, little greenery, and poor public facilities and infrastructure. I have experienced moving up the socio-economic ladder gradually in different kampungs: from a small house in an off-street kampung in Menteng Atas to a big house in an on-street kampung in Pondok Labu; from poor to better environment; from low to upper-middle socio-economic status; from dense kampung to dispersed, sparsely occupied kampung; from city centre to outskirts of city; and from barren kampung to a green kampung. I experienced no problems in living in those different kampungs because I started life at the bottom. Figure 6. My neighbours in Pondok Labu (Source: sketch by author) Pondok Labu is an example of a mixture of life styles, between kota and kampung styles, and between urban and rural patterns of behaviour. On the one hand, people who have moved from the inner city (kota) have to adapt to the kampung manner, and on the other hand, the indigenous people have to understand and try to accept kota lifestyles. I did not have any difficulty in adapting to kampung behaviour because I was from an inner kampung, which is not so much different from the peripheral kampungs. It is different for people who have moved from Menteng to this kampung. They need time to adapt to the social harmony of a kampung. The indigenous people from this kampung or surroundings have the opportunity of getting jobs from the new residents as drivers, domestic servants, gardeners and domestic satpam (security unit). It is different when poor people from kampungs in the city centre have been removed by force to the outskirts of the city. They will face big problems. Whereas I moved closer to my work place they finished far away from their work place in the city. They do not own a vehicle to commute more easily and faster to their work place, and the public transport is usually inadequate. Even though I now live in a better environment, I do understand why and how people live in kampungs in the city. It is different when the policy-makers or city planners have never experienced life in kampungs. They only know that kampungs are poor, but they do not know why and how the people live there. The suspicion must be that, as the advocates of kota, they will have difficulty seeing the merits of kampungs and the richness of their resources of social capital represented in rukun and gotong royong. Among the indigenous people, social harmony is still maintained. However, it is not as strong for the new residents, because they need time to adapt to this behaviour. Low social level servant groups can be a bridge or ‘agent of social harmony’ to build better relationships between residents, indigenous and new. In fact, the servants’ groups have a social harmony among themselves. Without permission from their majikan (boss), they are free to lend or borrow any household stuff, such as ladders, construction material, car tools and kitchen utensils. They even help each other when someone needs assistance to do heavy work or to solve problems. In the evening, after working, they come together in front of the houses or along the street and chat to each other about their daily experiences. The description of my own lived experiences in kampungs in this paper provides a series of themes for thinking about and analyzing the experiences of others, which I will take further in the next research. These themes are: 1) social relationships (rukun, gotong-royong, and the role of society leaders); 2) spaces, public and social facilities (lanes, open spaces, warungs, pasars, langgars, and masjids, and their intricacy and absence of ‘order’ in the sense of kota); 3) locality and distance (including the dependence on public and informal modes of transport); 4) territory (RT and RW); and 5) conflicts and the mechanism for dealing with them. Jakarta without servants would be a paralyzed city. As a result of a dependence upon servants, Jakarta experiences another big problem at least once a year. Annually, at every Idul Fitrie season, almost 2 million people—and a majority of them are servants—leave Jakarta to visit their home towns to celebrate Idul Fitrie with their parents or relatives.12 Even though the servants are from desas, from 12 Indonesians have a tradition of ‘mudik’ or going back to their home town or home desa every Idul Fitrie season to celebrate Islam’s great day of Idul Fitrie. At a national scale, the number of people who visit their desa is estimated at 14.8 million (Kompas 1.11.2001) including 2 million from Jakarta (Kompas 8.11.2002). The majority of them queue for two or three days in stations of bus terminals to get public transport to their destinations. This number increase every year about 7–10 percent. Thus, Jakarta was predicted to obtain new migration, around 700,000 to one million people in the year 2003. 21 Living in the Kampungs ▌FORUM. Vol.7. References Bruyn, S. T. (1966) The Human Perspective in Sociology: The Methodology of Participant Observation, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, Inc. Fillstead, W. J. ed. (1970) Qualitative Methodology: Firsthand Involvement with the Social World, Chicago, Rand McNally College Publishing Company. Heuken, ASJ and Pamungkas G. (1997) Menteng: Kota taman pertama di Indonesia, Jakarta, Enka Parahiyangan. Holtorf, G. W. (1998) Jabotabek Street Atlas, Jakarta, PT Intermasa. Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space, (translated by Nicholson-Smith, D.), Oxford, Blackwells. Lynch, K. (1996) The Image of The City, Cambridge, The MIT Press. Marcussen, L. (1990) Third world housing in Social and Spatial Development, Newcastle, Athenaeum Press Ltd. Pemprov. DKI Jakarta (1991) Master Plan ’Jakarta 2005’, Jakarta, DKI Jakarta. Pemprov. DKI Jakarta (1999) Master Plan ’Jakarta 2010’, Jakarta, DKI Jakarta. 22