NUMBERING SUGARS

advertisement

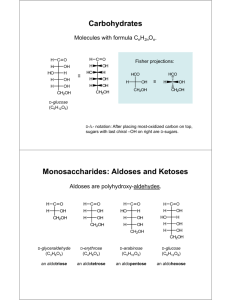

NUMBERING SUGARS How you number a sugar depends on whether it’s an aldose or a ketose, so I’m going to go through the numbering conventions for each type of sugar separately, looking first at linear models and then looking at the ring model. ALDOSES Aldoses are called aldoses because they have an aldehyde group in them. An aldehyde looks like this where R can be pretty much anything and is pretty often a hydrocarbon chain. In an aldose, the R group is a chain of carbons with one hydrogen and one hydroxyl coming off each carbon (the carbon at the end gets 2 hydrogens). We’re going to use deoxyribose and ribose as our example aldoses, since those are the ones that are most important for you to be able to number in this course (so you can tell the 3’ and 5’ ends, and be able to distinguish between ribose and deoxyribose). deoxyribose ribose When you number the carbons in an aldose, start at the carbon that’s double-bonded to the oxygen (called the carbonyl carbon) and go down the chain. The models that we’ve been looking at are simple linear models. You may see sugars shown in what’s called the Fischer model, named for Emil Fischer who was a super important sugar chemist. Each intersection or bend is a carbon atom. In those, you start at the top and go to the bottom. In aldose rings, there is always an O at the top of the ring, and a sort of arm coming off the side. In this deoxyribose drawing the arm is a little more obvious because it’s waving at you; in the ribose drawing, it’s the CH2OH you see coming off the top. (A note about these diagrams: thick lines show bonds that come out toward you; striped lines show bonds that go back away from you; squiggly lines show bonds that can be either way. It’s nothing to worry about at this juncture but it’s immeasurably helpful when you have to visualize these things in 3D) Start numbering at the carbon that does not have the arm, go around the ring, and then go up on the arm. This is completely consistent with the numbering used on the linear and Fischer models and has to do with how the sugars become rings (look up keto-enol tautomerization for more about that; you’re also welcome to check out my organic textbook for some nice diagrams that help to visualize this process). And that’s it for aldoses! KETOSES Ketoses are called ketoses because they have a ketone group in them. Ketones look like this: where R is just the same as with aldehydes. R is used throughout organic chemistry to signify pretty much any kind of attachment, like n is used in math to signify pretty much any number. With ketoses, the kind of R you find is the same as with aldoses—that is, carbons with one hydrogen and one hydroxyl coming off each C, with the last C getting an extra hydrogen. That R group is characteristic of sugars, so it makes sense that it’s the same between aldoses and ketoses. We’re using fructose as our example ketose. So, you can see in fructose that the R group on one side is not the same as the R group on the other side. It’s still carbons with hydroxyls and hydrogens, but one R group is longer than the other. This is awesome, because it tells us where to start numbering. You start at the end-most carbon on the shorter side. If you have identical R groups on either side, then just start at one end and go along the line. Since it’s symmetric, it’s okay to start at either end. Fischer models of ketoses are always oriented such that the shorter side is on top, so you can just number down the line from top to bottom. You can also number top to bottom with symmetric sugars. In ketose rings, because of how the ring forms, you can end up with one or two arms. For a ring with one arm, start numbering at he endmost carbon in the arm, and then go around the ring. For a ring with two arms, if the arms are symmetric, start at the endmost carbon on one arm, go around, and end at the endmost carbon on the other arm. Notice that in its linear form, fructose has two different R groups, but its arms are symmetric! If the arms aren’t symmetric, then number starting at the endmost carbon on the shortest arm, go around the ring, and end at the endmost carbon on the longer arm. So yeah! That’s numbering sugars!