The Institutional Foundations of Supranationalism in the European

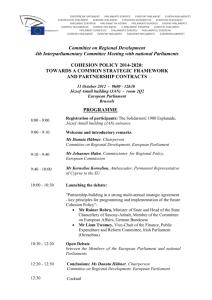

advertisement