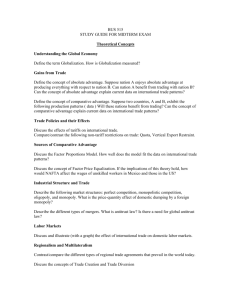

Chapter Preview: NAFTA Revisited Ch 1 Overview

advertisement