In 1976, the Dominican writer Jean Rhys published a collection of

advertisement

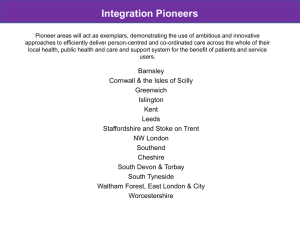

So soon does one learn the bitter lesson that humanity is never content just to differ from you and let it go at that. Never. They must interfere, actively and grimly between your thoughts and yourself—with the passionate wish to level up everybody and everything. (“Mixing Cocktails,” 37, found in Rhys 1992) In 1976, the Dominican writer Jean Rhys published a collection of short stories in “Sleep It Off, Lady”. The first story within the volume, ‘Pioneers, Oh Pioneers’, concerns the fate of Mr. Ramage, a young Englishman who comes to Dominica, buys an estate, marries a colored woman of a questionable reputation and attempts to go native. The members of both the black and white population see his behavior as highly odd. He is criticized in a spiteful, false and misleading way by the whites and in the end he commits suicide or is finally killed. Very important also, is the young girl Rosalie, whose empathy for and identification with the Ramage is central to the story’s theme, though it lies on the periphery of it (Staley, p127). The story is set in Dominica in November of 1899 more than half a century after the abolishment of slavery. Significantly this date introduces a sense of uncertainty and displacement, on the edge as it was of two seasons (fall and winter), two years (1899 and 1900), and two centuries (the 19th and the 20th). Because of this emphasis on a binary division this year also comes to be a symbol of the contrast and juxtaposition of the two major worlds within the text, that of the blacks and the whites, and of the idea that crossing this cultural gap is very difficult if not impossible. Also at the opening of the story the significance of the depiction of Market Street, its people, sights and smells is also much more than mere setting. According to Malcolm, 1996 (p85) this is where images of the West Indies and England physically clash in the mind of the narrator in the form of the black and white women who are moving about in the street. Miss Menzies wears a “thick dark riding habit” while the black women wear “gaily striped turbans and highwaisted dresses” (Rhys p9). So, even clothes come to be used as a motif to illustrate the clear division of the society. Also this divided world foreshadows the inability of the protagonist, Ramage, to fit in any one group or place. In terms of the narrative perspective, this story is written as a third person limited omniscient piece since the narrator does not participate in the action of the story as one of the characters, but still has the knowledge of how certain characters feel and what they think. This perspective really makes a difference to the effect of the work because while we are given glimpses of the story from the consciousness of Rosalie (Rhys p9 and 16), Dr Cox (Rhys p10-, Eliot (p12-13) and even Mrs. Cox (p 16-17)we are never allowed into the consciousness of the major character Ramage. This point of view also helps to foster within the reader a sense of distrust and uncertainty as to the truth of the gossip that surrounds Ramage. We are left wondering whether this ‘king among men” is capable of committing the terrible act of murdering his own wife and we are allowed to witness, first hand, the power of hearsay, by how it shapes our own perspectives and opinions toward Ramage until the very end. In this story characterization is also used skillfully to highlight the themes of victimization and powerlessness. Usually within the fiction of Jean Rhys, men are the oppressors however in this story Ramage is undisputedly a powerless and victimized outsider who comes to identify more, with the women of Rhy’s fiction (Malcolm p82). He is described as having hands that were ‘long and slender for such a big man’(Rhys p11), a clearly feminine quality which alludes to the idea that his personality is not compatible with the expectations society has of him since gentleness is an ill suited quality to a colonist. The fact that he consciously decides to set himself apart from others and that this actively contributes to his victimization is even more tragic. It has been said that Rhy’s picture of a male destroyed by the contradictions of a society polarized by race and class is even more powerful because she has used a figure of traditional male power and authority to do this, the white male colonist (Malcolm p83). Thus we can appreciate the irony that the seemingly admiring title “Pioneers, Oh, Pioneers” is actually more like sarcasm or mockery. In terms of character Ramage is very interesting as well. Initially he seems to posses all of the qualities that would allow him to be liked and accepted by people. He is described as handsome, tall, and dressed in tropical whites and having money to invest in the small island (Rhys, p 10). Indeed as Malcolm has rightfully pointed out he has the makings of a cultural icon. Ramage however comes to be associated not with the empowered males of Rhy’s fiction but with the powerless and ostracized female group. He rejects every opportunity to belong and comes to be seen as very unsociable. His rejection of the very institutions that support white island society, the dances, tennis parties and moonlight picnics(Rhys p10), sets him apart at odd and what is more, as dangerous. His choice not to fit in is nonsensical to both white and black society. Both of whom can only reconcile his behavior as being that of a lunatic or zombie. Just as the song he sings to Rosalie, Ramage is a “black sheep” among the English on the island, who declare him mad, and is hated by the blacks who think he is a murdering cannibal. In the end he is destroyed because he can find no peaceful place to belong and in him Rhys extends her gallery of outsiders to include a white European male something very similar to what she does with the damned and lost Rochester figure in Wide Sargasso Sea.