Voyage in the Dark A transnational feminist text? the novel

advertisement

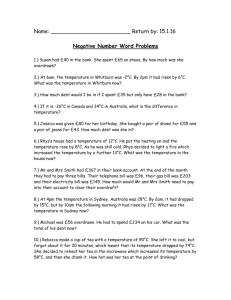

Jean Rhys, Voyage in the Dark A transnational feminist text? Spatial and temporal co-ordinates of the novel London at the turn of the 20th c • Capital city/World city • Capital in both senses of the world: Pre-eminent city of England; centre of capital its wealth and grandeur created by the Industrial Revolution, but also crucially by its colonies (plantations in the Caribbean, colonization of India and Africa) brought amazing amounts of wealth to the capital city -Global finance and trade but also world cultures (empire exhibitions since the 19th c; the British Museum; the anthropological societies) London Images Crystal Palace, 1851 British Empire Exhibition, 1924 Wembley Shopping and fashion The fog of London Voyage in the Dark • Recall the opening sequences of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (Rhys’s novel’s title can be seen as registering that narrative—London as the space of darkness for the colonized subject) • Within a geometric imagination, the city is figured as a series of concentric circles. In the inner circle, the masculine sphere constitutes the center of power in the city, with the women at the periphery. In the global sphere, the European city constitutes the core of the empire, its colonies the periphery. These very geometrics of modernist urbanism and imperialism are mapped and then unraveled in Rhys’s novel London/Caribbean -situated at the intersection of colonial and postcolonial worlds, the latter haunting the former, the former displaced on to future dreams of difference erupting in the metropolis -The Caribbean appears as an alley in London— its smells, colours, taste (Francine’s eating mango—sensual image vs the stale breakfast trays in bedsits) and heat in contrast with the coldness and dankness, greyness and colourlessness of London Gendering the city • The flaneur: a stroller, a man of leisure in the city (idler), a dandy, an urban explorer. A literary type in French literature, viz. poetry of Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867). Theorised in the work of Walter Benjamin, as the quintessential figure of modern/ist capitalism. Walking/Mapping/Self-fashioning • the novel represents reading, walking and mapping as interlinked urban social practices framed within a global imperial system • female labor in the city, or women’s work more generally, as a critical counterpoint to the capitalist arrangements that underpinned the modernist city; the flaneur, the man about town, embodied modernist anxieties about intellectual labor (elaborated through the elision of domestic and sexual labor), the labor of fashioning oneself as a modern subject in the city is gendered. • working-class women involved in increasingly alienated sexual labor in the service of the capitalist urban machine. • Oiling this machine are men with new money, engaged in Citybased transnational transactions that operate alongside, if not entirely depend on, the traffic in the underclass of women. Modernist city/subjectivity • Modernist urbanism—crossed over by colonial history • Novel written against “standard urban narratives” • Voyage in the Dark seeps into the interstices of literary modernism’s representations of the city--masculine and feminine modernities as disjunctive and differentially available to literary representation. • through the figuration of alternative, dissident bodies that challenge hegemonic narratives of modernist urbanism. Rhys interpolates her protagonist Anna's sexual, economic and ultimately political body within the spaces of London in order to insert, quite materially, the question of women’s materiality within the framework of colonial capitalism. Transnational Time • • • • Early 20th c War/colonialism Modernity/modernism Sense of break with the past; fragmentation of time; past-present-future: discontinuous Ruptures and discrepancies • The radicalizing moment of the years preceding World War I (without naming it) and its attendant rupturing of social, especially gendered meanings of public and private, capital and labor, colonial power and class struggles. • Rhys’s modernism consists of elaborating these various discrepant realities (in modernist fashion, the discrepancy is apprehended as an opposition between the inner world of the protagonist and an uncomprehending, seemingly messy objective reality) Jean Rhys, a transnational biography Rhys • • • • • • • Rhys’s biography (personal and writerly) itself is transnational: In 1907, at the age of sixteen, Rhys left her family in the Caribbean and arrived in England. She spent the years leading up to World War I and the subsequent wartime years in London, returning to the city again after spending the decade of the 1920s in Paris. mixed national heritage as a white creole from Dominica, itself a hybrid, multi-layered place with its own history of multiple colonizations and diasporic movements. Secured by the British in 1805, the influence of French culture on Dominica remained such that the African-Caribbean majority spoke a French patois. Here Rhys was part of a small Protestant elite in a majority Catholic culture. She went to a Catholic school where whites were in a minority. The daughter of a Welsh father (whose own mother was Irish), Rhys referred to her cultural origins as “pseudo-English” in her memoir Smile Please. Perhaps as an extension of this, Rhys also occupied an ambiguous place within the racial and sexual demarcations of the imperial metropolis. Views of the Caribbean in the metropole associated it with degeneracy, vulgarity, sexual immorality, illegitimacy, as a resolutely “unEnglish kind of place”. In particular, white creole women, the West Indian heiresses, were likened to the figure of the Hottentot Venus, a nineteenth century racialized vernacular image for pathologically sexualized women. The most celebrated literary example of a white creole woman who meets a tragic fate is of course the crazed Bertha of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre—violent, bestial, degenerate and transgressive of Victorian codes of femininity and domesticity. Liminal Rhys • Rhys continually contests boundaries of identity, nation and culture. • in her memoir, Smile Please, Rhys represents herself as an alienated and reviled stranger in the imperial heartland. • Ford Madox Ford identified Rhys’s national origin as the source of her peripheral vision of the imperial metropolis: “Coming from the Antilles, with a terrifying insight, and a terrific—an almost lurid!—passion for stating the case of the underdog, she has let her pen loose on the Left Banks of the Old World—on its gaols, its studios, its salons, its cafes, its criminals, its midinettes…”. • Helen Carr poinst out that “as a white creole from Dominica she was ‘West Indian’ in a different way…” Kenneth Ramchand writes of the historical predicament of the white creole as consisting of a “terrified consciousness” emanating from a sense of belonging to nowhere. Judith Kegan Gardiner notes that "on both sides of the Atlantic (Rhys) felt in the position of a member of a racial minority living among a resentful majority”. Black or white • Critics have read Rhys as a black writer, though it is unclear how satisfied she would have been with such a classification. • Such a critical move is complicated by the fact that as a white descendant of slave-owners, the West Indies could never be home, in either a moral or an existential sense, for Rhys. • Nevertheless, Rhys’s readability as a black writer only underscores her troubled relationship to metropolitan modernity. Rhys has thus emerged in Anglophone modernist literary history as the quintessential outsider figure. In particular, her female protagonists embody this sense of being outside class, race and nationality assignations. Thus the woman on the edge of modernist urbanism was to become a defining figure of resistance in Rhys’s fiction. Transnational Modernism • • • • • Her remarkable biography weaves together dispersed geographies even as it displaces metropolitan modernity onto the black trans-Atlantic routes of migrating and circulating bodies, cultures, texts and commodities Rhys has occupied a more or less peripheral position vis a vis the modernist "tradition". a perpetual sense of the problem of placing her within any canon, locating her uncertain place partly in the gender politics of the modernist literary tradition, the predominantly Anglocentric framing of Rhys’s output as a modernist writer, a reading that gets troubled when we place her work within trans-national European/Continental and Afro-Caribbean literary traditions, political concerns and theoretical innovations. Such a reading allows for modernism to be read as a trans-national movement and project located within the imperial world system. At the same time, it can be viewed as a dissident project aimed at interrupting the dominant routes of the global trade in people, commodities, texts and cultures through the insertion of the peripheries as important centers of artistic activity, creative sensibilities and revolutionary energies.