The Shadow of Shadows

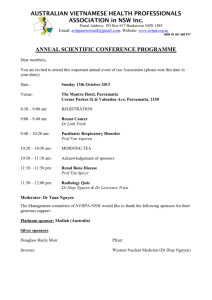

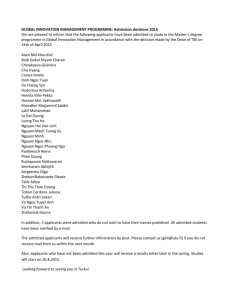

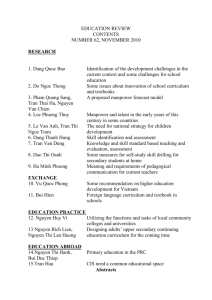

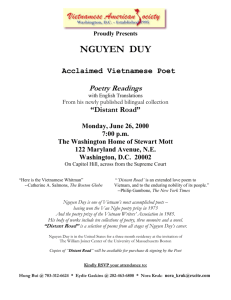

advertisement