To - WBI Conference Proceedings.

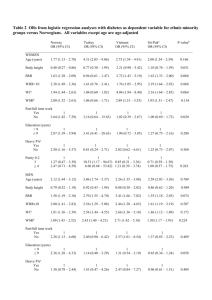

advertisement

Proceedings of 25th International Business Research Conference 13 - 14 January, 2014, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-42-9 Kaizen Kosaku or New Business Model Innovation Paradigm Jehan, S.N.a*, Wali Ullahb, Khan M.A.c and Jehan, S. Q.d Japanese businesses are at crossroads where they are faced with an uphill task to maintain their position as leaders of innovation in electronics industry. While non-Japanese companies seem to have initiative and momentum at the moment, Japanese companies in the industry seem to be stuck with inertia and without an appropriate strategy to get out of the conundrum. Kaizen – Kousaku seems to have hit a halt for some time. In this paper we analyze the factors behind the present situation and put forward our suggestions to come out of the apparent paralysis that Japanese companies are facing at the moment. Our findings suggest that while Japanese companies are still good at innovation and R&D spending, they are unable to properly integrate the process of innovation into their business models. The ineptitude of the Japanese companies in the electronics industry appears to be an outcome of their insistence on outmoded business model and inability to adapt fast enough to the changing business paradigms. Key words: Kaizen – Kousaku, Japanese Electronics Companies, Technology Management, Business Model Innovation. Introduction Old habits don’t go easy; and Japanese Electronics Companies1 (JECs), habitual of innovating, are still hard at doing that as the time passes by. But not all things done habitually may be too much in tune with the needs of the time. It is another fact that if you do not keep making history, you end up living in history. It may sound an overstatement that JECs are living in history, but nonetheless there is certainly something amiss about them as we look at the present times, the peers that populate its environs and habits that JECs are still stuck with, despite losing all that ground they held in the previous and earlier decades. Plainly said, it seems that JECs are at crossroads where they are poised with a situation that require a complete overhaul of the ways in which they innovate, commoditize the technology and the way in which they integrate their management of technology and innovation (MTI) with the business model they rely on. While the peers in competition, from rest of the world, are gaining grounds by introducing new business models and integrating their technologies with the customer needs, JECs seem to be striving to retain already held ground. In this paper we ascertain what is awry with JECs and what can be possible solution to their quandary. In doing so, we shall bring to forth the data and facts that make it clear that JECs are losing, not in a singular way; we also attempt to point towards the remedial measure i.e. business model innovation (BMI) that will have a greater potential in getting JECs through the crossroads. _________________________________________________________ a Jehan, S.N. , Institute For International Education, Tohoku University, Japan. b Wali Ullah , Tohoku University, Japan. C Khan M.A. , Comsats University, Islamabad, Pakistan. D Jehan, S. Q. , University of Antwerp, Belgium. 1 Proceedings of 25th International Business Research Conference 13 - 14 January, 2014, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-42-9 In today’s cutthroat corporate competitive times, innovation is one of the key elements of corporate success. As more companies seek to exploit the emerging opportunities and provide similar or novel product or service targeted on new or existing markets, innovation is a key differentiator. It is no longer just an option to add value and deliver extra competitive advantage; rather it now lies at the core of a company’s survival strategy. Taking only new product development as a driver to innovation based success would not be enough; instead MTI would need to be incorporated as integral part of BMI in order to ensure that innovative inertia is broken and innovative momentum translates into business success. 2. The Literature & the Trends The design and consideration of BMI is becoming increasingly relevant today, as the business environs are increasingly laced with change and uncertainty. When it comes to JECs, despite the fact that they are no longer performing as well as they used to in the global market, most existing studies are from 1990s concerning JECs’ success in product innovation. Few have looked at JECs from the point of BMI. Even those studies, upon discussing JECs’ capabilities of BMI, mainly focused on the managerial practice of new product development. Chesbrough (2002) states that established firms as well as startups take technology to market through a venture shaped by a specific business model, whether explicitly considered or implicitly embodied in the act of innovation [3]. It is important for an innovation to be followed by the launch of a successful commercial product or service in order to bring out the value addition sought by the innovative process. We can see that a number of recent decades’ successful businesses have been able to do so only by bringing in new innovation models into play. Understanding the dynamics and designs of BMI is important in order to understand its horizontal and vertical linkages with the internal and external business processes. So, it will be important to lay down the details on BMI of JECs in a holistic and integrated manner to enhance added value factor for all involved. Sugumaran (2002) describes the essentialness of BMI as a source of sustainable competitive advancement in the new business environment that is characterized as dynamic, discontinuous and radical pace of change [6]. Kodama (2005) examined the dynamism of the knowledge creation process at Fujitsu Ltd., and came to the conclusion that the synthesizing capability of the network leader group enabled Fujitsu to build new business models aimed at customers and achieve a successful outcome ahead of Japanese competitors [5]. However Kodama did not go further enough and did not give us a thorough analysis of Fujitsu’s business model. Also, this is a sort of case study that falls short of analyzing in depth the industry as a whole. Watanabe (2009) concluded that the bad performance of product innovation including becoming too dependent on attaining technologies through mergers and acquisitions [7]. Unsurprisingly, however, US companies have been able to generate larger revenues by focusing on innovation for growth and renewal. Johnson (2010) mentions that success of US competitors of JECs is largely due to seizing the white space by focusing on the BMI [4]. It is plainly clear that studying the BMI’s relevance with business success is very much relevant in today’s times; and scarcity or lack of a comprehensive approach calls for further studies to understand the situation. Therefore, we believe by looking into the dilemma JECs are faced with from the angle of BMI, we shall have a better understanding of the issues involved and that in turn can pave a road for future studies on this issue. Innovation is not entirely reflected by the number of successful patents, however, it has become an 2 Proceedings of 25th International Business Research Conference 13 - 14 January, 2014, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-42-9 industry norm to accept the number as a performance indicator. While, we shall not overemphasize the numbers as such, and we also cannot ignore that patent war can at times reflect innovative inertia taking hold, nevertheless, in this section we shall look into the statistics to reflect upon the situation from a quantitative standpoint. Figure 1: Total Number of Patents (1990~2007) Source: WIPO Statistics Database, September 2010 So it is important, first, to analyze the trend and then to get behind the reasons for such a development, if one plans to put forward any way-out of the present conundrum faced by JECs. At present it seems that JECs, that dominated patents market in later decades of the last century, have lost momentum to none else but to their Korean rivals, with China trailing behind Korea, especially in consumer electronics. Today, electronic giants like Sony and Panasonic seem struggling to keep up with Korean rivals like Samsung and LG, once considered too far behind to catch up. However, as a whole, the picture for Japanese patents is not as dismal as one would tend to think. During the period from 1990 to 2007, Japan outperformed US, its closest rival, by a ratio of 3 to 1 (Figure 1). Japanese companies per se still dominate the electronics patent holders club as well; but it is the trend that is worrying enough for many in Japan to hold their breath. Trend from the beginning of 2000 is that non-Japanese electronics companies are increasing their patents portfolio at an increasingly higher rate than the Japanese companies have been able to do (Figure 2). Figure 2: Comparative Patents Trend 1990 ~2007 Source: WIPO Statistics Database, September 2010 What is more worrying, than just the decreasing gap between JECs and the rivals, is the inability on the part of Japanese corporations to reach a least cost approach to innovate and deliver goods and services 3 Proceedings of 25th International Business Research Conference 13 - 14 January, 2014, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-42-9 while customers’ willingness to pay (WTP) is not rising. It is obvious (Figure 3) that Japan’s R&D expenditure is still the highest as a percentage of GDP when compared with other close rivals. However, the rivals appear to be making better on the revenue growth associated with innovative performance, especially in the electronics field. On the output side of the innovation efforts, total factor productivity (TFP) is experiencing a decline in comparison with competitive peers. So, it is imperative that JECs come up with ways and means to be efficient with innovation cost and to enhance the value created by the innovative process. In the next section we shall explain the linkages between the value chain and innovative process. Input Model Innovation would be necessary in order to engage in a cost efficient way to innovate. While R&D expenditure is main innovation input cost, it is Figure 3: R&D Expenditure to GDP Ratio - Trend Source: ‘Science & Technology Indicators’ 2010 by NISTEP 3. Innovation & Value Chain JECs situation calls for creating new value creation avenues in the process of innovation strategy formation in tandem with business model innovation. We understand that value-enhancing options for JECs will be in the following action areas: Input Model Innovation Revenue Model Innovation Business Model Innovation necessary to engage in an efficient model of R&D-innovation effort. Industry wide horizontal as well as vertical linkages will be necessary in order to ensure that innovation results in products or services that can generate a comparable stream of revenue. An in-house innovative aloof from externals results in duplicate (or detached) innovations, leads to increased R&D expenditure and produces many dead-enders. Revenue Model Innovation calls for approaching the market in a way that results in greater market acceptability as well applicability of the technology when it is commoditized. Apple’s business model has a great imprint of its revenue generation model. However, a closer look will reveal that the capacity of Apple’s revenue models to generate enough revenues is ingrained in the way its products are developed and designed. Apple’s innovation model is also an epitome of standardized modular commoditization that allows Apple’s other products and many other software and content producers to follow the development and revenue trail left by Apple’s products. Products like I-Phone, I-Pad, I-Pod and now I-Cloud all are designed in a way that allows horizontal as well as vertical networking that benefits both Apple as well as 4 Proceedings of 25th International Business Research Conference 13 - 14 January, 2014, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-42-9 many peers in the market (figure 4). It is interesting to note that development of a single product creates enormous opportunities for a long line of followers, e.g. for software and gadget developers, once the product is launched by Apple. It should, however, be noted that this will be possible only in a world that follows and promotes a standardized modular commoditization that is integrated in a network style right from the time of its development through all the later stages. Apple’s model is paying off in a way that makes many peers envy its successes. A large number of analysts have regarded Apple’s business model as ‘Iconic & Sustainable’ due to its integrated and innovative business approach (Seeking Alpha 2011) [1]. Figure: 4: Apple’s Networked Innovation Design Source: Adopted from Apple’s Website Business Model Innovation requires that the whole innovation and business paradigm be considered in a strategic perspective. That would mean that all stakeholders (owners, industry, competitors, customer, society etc.), the environment (present and the expected) should be considered in a holistic manner and all these factors be made an integral part of the planning, evaluation and control process of the firm’s business model. 4. New BMI Paradigm Present BMI Status of JECs vis-à-vis Peers At the heart of the problem appears to be an apparent tug of war between the Confucian kaizen and western disruptive ways of technology. Kaizen Kousaku has long been a way to step-by-step and incremental technological development; rather the whole Japanese innovation paradigm is modeled around in-house innovation. In-house innovation strategy does not focus much on networking and standard based modular/commoditized way of business rather it reflects a tendency to maintain a state of homeostasis. In-house style of innovation has worked for JECs in 20th century; but it seems that the 21st century’s business challenges would take a little more than that. It is a time when standards based modular commoditization has taken over. BMI now encompasses more than in-house; rather innovation in tandem with networking seems to be the order of the day. We understand that major problem with the JECs right now is the cost effectiveness of the innovative process and inability to contribute effectively to the TFP. That means the whole business paradigm for JECs needs to be remodeled in a way that allows networking and innovation needs to be a little more disruptive in nature than mere incrementally developed over a long period of time (Figure 5). 5 Proceedings of 25th International Business Research Conference 13 - 14 January, 2014, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-42-9 Figure 5: Innovation & Business Paradigm Nexus The innovation and business nexus can be explained as taking four forms. As is in the Figure 5, the in-house innovation and harmonious business style would result mostly in slackers and JECs are an embodiment of this group of players. The Japanese slackers are the businesses that grow and feed on the Kaizen Kousaku. Kaizen Kousaku served Japanese companies well in the times of early industrialization of Japan and through most part of the last century. However it seems that Kaizen Kousaku only will be incapable of coming up to the challenges of today’s business environment that is characterized by all creeping and unstoppable change and uncertainty. Bangers and altruistic businesses are lacking at least one of the traits i.e. either lack networking or are not disruptive enough. While we may find cases of few firms straying into these two fields; but chances of immense success and continued existence for banger and altruistic businesses will be hard to imagine in a globally interconnected and fast changing world that we live in today. Futuristic businesses would reach out while developing and would still be able to come up with technologies disruptive enough to make substantial business gains. Getting behind the success of futuristic businesses would require studying the underlying currents of the time. The essence of the time is change, and most people sense more change around them now and even more of it to come more rapidly in the business environment in times to come. A study of 1541 CEOs by IBM Research found that most CEO anticipate more change and complexity to populate the business environs in 3 to 5 years and expect this to occur exponentially in the times beyond [2]. The same survey finds that most Japanese CEOs are not too worried about the change or complexity that is in the offing. This complicity is understandable keeping in mind that Japanese companies are good at handling complex and tedious technologies and are used to spending a long time on one technology or process to understand all the complexity that comes with it. However, it is not only the complexity that needs to be taken care of; it is also the speed, cost and the environs that need to be considered. In-house technologies have been found to be more expensive and sometimes these technologies developed in isolation from the peers and clients have resulted into deadeners. A study of the innovation strategies of many recent successful electronics firms revealed that both the nature of the technology as well as the way it was developed had a major bearing upon the success of the firms’ innovative efforts. Most of these firms who introduced disruptive technologies were using the networked model of developing and deploying them. Companies like Apple and Dell are successful examples of companies that adopted a broad industry wide network based business model. New BMI Paradigm Explained After having thoroughly considered the causes, implications and the options available for JECs to move on in the face of all the challenges they face today, in Figure 6 we lay down a new BMI paradigm for JECs, if 6 Proceedings of 25th International Business Research Conference 13 - 14 January, 2014, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-42-9 they have to break the innovative inertia and regain the momentum. The BMI paradigm laid out in the figure 6 emphasizes a strategic design of the BMI. Below we briefly explain the implications of most parts of the paradigm in singular detail. Figure 6: JECs & New BMI Paradigm The input model innovation design should ensure at least two bare minimums for the innovative leadership and effectiveness i.e. cost effectiveness and financially viable innovations. In-house innovation coupled with acquired innovation would ensure the relevance as well as the viability of the innovative effort. In-House innovation has been the Achilles heel of the innovation strategy of most of the JECs so far. This will have to continue, but would need to be aided by the outside influences on the product or service innovation plans. This leads us to the next point i.e. acquired innovation. While most innovation cost would be composed of R&D spending; a little of additional cost spent on environmental scanning and end user affinity would ultimately result in reduced input-to-output ratio. In order to ensure the relevance of the innovative outcome, streamlining the innovative activities with the market requirements would be imperative. This also entails scanning for innovation trends in the business environs and aligning in-house position with the innovations that can be acquired from outside, if possible and necessary. This will also result in reducing unnecessary R&D spending and will eliminate the costs incurred on producing dead-enders or anemic success. The combined effect of the strategy mentioned here would be a cost effective and viable innovative outcome that can justify the R&D spending and a workable input model of innovation. Enhancing the innovative effort’s value and thus increasing TFP, which is not explainable by other factors, will require certain remodeling on the revenue side too. This would entail a cross industry alignment of the potential uses for the end product or service. Laying out revenue generation model that is not entirely inward focusing requires horizontal as well as vertical standards based commoditized alignment of the product or service. The standardized modular commoditization would allow networked as well as peripheral utility of the innovative outcome, thus enhancing the possibility of a larger revenue generation model. It would also require flexibility needed for a broad based utility focused innovative architecture. An inclusive revenue generation model would then only needs to be complimented by comprehensive networking of in-house as well as industry-wide innovative efforts. This would mean aligning with industry standards, modularization of the output in areas that are not a part of future in-house innovation plans, and commoditization that allows a wider proliferation of the outcome in the market arena. Hence the three-staged business model innovation would ensure that JECs would continue to be able to do so in future as well. This will ingratiate the innovative efforts with the change and uncertainty that is too pervasive in today’s corporate environment. 7 Proceedings of 25th International Business Research Conference 13 - 14 January, 2014, Taj Hotel, Cape Town, South Africa, ISBN: 978-1-922069-42-9 Last but not least, the seed forward channels and seed back channels would be necessary to ensure a strategic focus of the whole business model. Without seed forwards information channel, it will be hard to cultivate market and industry wide networks necessary for the whole new paradigm. Seed back channels would allow the necessary feedback required to align the in-house innovative activities with the market and environmental requirements like cost, revenue or networking requirements. 5. Conclusion Through the data presented and analysis carried out in this paper we have been able to clearly identify that JECs are faced with momentous task of clearing through the crossroads at which they find themselves today. Their leadership, though still in place for the time being, is eroding fast in the wake of far aggressive innovators in the peers around them. In order to ensure that they are able to continue enjoying their past glory, JECs need a paradigm shift in the way the innovative effort is planned, executed and brought to bear fruit in today’s fast paced, uncertain and ever changing business environs. We found that Kaizen Kosaku, while still important from Japanese perspective, will have to be aided by means of acquired technologies. This does not mean that they should start importing technologies that developed are always outside the firm’s indigenous efforts; rather they need to align the in-house innovative effort with the peers’ innovative efforts and see where and when they can cooperate or avoid duplicating the technology that might already be available at reasonable acquisition cost. This would ensure that input required for the innovative effort is matched with the value of the output. Thorough revenue generation model innovation would be needed to ensure greater revenue generating opportunities. This entails developing as well as looking for standards that would allow a modularized commoditization of the final output with the industry and market requirements that is also commensurate with firms’ strategic innovative plans. Finally aligning the internal and external efforts through effective industry and enterprise wide networking would allow JECs to be able to adopt an entirely new business paradigm that is cost-effective, enhances TFP and can sail the JECs through ever changing and uncertain times that they are passing through and will have to face in times to come. References [1] Apple Business Model Is Iconic And Sustainable from October 2011 Seeking Alpha http://seekingalpha.com/article/298572-apple-business-model-is-iconic-and-sustainable?ifp=0&source =email_tech_daily [2] Capitalizing on Complexity – Insights from 2010 IBM Global CEO Study, The IBM Institute for Business Value, May 2010 accessed on 10/06/2010 http://www-935.ibm.com/services/c-suite/series-download.html [3] Chesbrough, H. and R. S. Rosenbloom, (2002). The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation's technology spin-off companies, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 11(3), pp. 529-555. [4] Johnson, M. W., (2010) Seizing the white space. Business model innovation for growth and renewal, Harvard Business Press, Boston, Mass. [5] Kodama, M. (2005). Knowledge creation through networked strategic communities: Case studies on new product development in Japanese companies, Long Range Planning, Vol.38(1), pp. 27-49. [6] Sugumaran, V. (2002). Intelligent support systems: knowledge management, IRM Press. [7] Watanabe, C., J.-H. Shin, et al., (2009), Learning and assimilation vs. M&A and innovation: Japan at the crossroads, Technology in Society, Vol 31(3), pp.218-231. 8