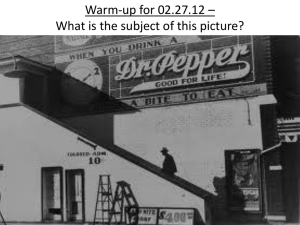

don't do the crime if you ever intend to vote again:1 challenging the

advertisement