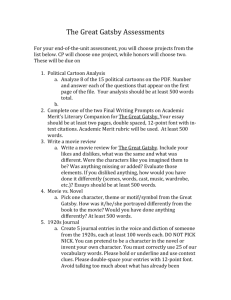

The Great Gatsby Study Materials: Alabama Shakespeare Festival

advertisement

The Alabama Shakespeare Festival 2014 Study Materials and Activities for adapted by Simon Levy Contact ASF at: www.asf.net 1.800.841-4273 Study materials written by Susan Willis, ASF Dramaturg swillis@asf.net 1 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Characters Nick Carraway, a Midwestern newcomer trying to make money in New York City Jay Gatsby, his wealthy neighbor on Long Island Daisy Buchanan, Nick's distant cousin, the woman Gatsby loves Tom Buchanan, Daisy's very wealthy husband Jordan Baker, Daisy's friend, a professional golfer Myrtle Wilson, Tom Buchanan's mistress George Wilson, Myrtle's husband, a mechanic Meyer Wolfshiem, Gatsby's business associate Mr. and Mrs. McKee, neighbors at Tom and Myrtle's New York City apartment Mrs. Michaelis, Wilson's neighbor A Cop (Two actors play the last five roles.) Setting: the summer of 1922 in New York City, on the Gold Coast of Long Island, and near the ash heaps between A Life magazine cover from 1927 by John Held— of course a flapper driving badly has a big yellow car— and the 1929 Rolls Royce Phantom used in the 1974 film On the cover: A treatment of Francis Cugat's famous jacket illustration for the first edition of the novel in 1925—called "the most eloquent jacket in American literary history" Welcome to the Jazz Age at ASF F. Scott Fitzgerald named the Jazz Age, and his life and art are considered cornerstones in its definition. Yet like Nick Carraway, Fitzgerald was in it without fully being of it; as an artist of great talent and honesty, he carried the sensibility of a not-rich-enough Midwesterner within him even as he found himself able to enjoy the American Dream come true—and also having to pay for it. Justly famous for his fiction and iconic lifestyle, Fitzgerald also has Alabama fame because he fell in love with a Montgomery girl, Zelda Sayre, and revised and published his first novel in order to win her hand in marriage. The couple were headliners of the American expatriate writing community in France during the late 1920s. The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald's masterpiece, captures the New York City of the early 1920s and the sensibilities of those who come to the city looking for a way to make their dreams of fortune and love come true. It is a rare work of artistry and a story that continues to feel timely almost 90 years later, a mirror still for our 21stcentury truths and for our illusions. About These Study Materials • If you are already teaching Fitzgerald's novel, these materials will supplement that endeavor by analyzing what happens when a famous novel changes genre—another angle on appreciating Fitzgerald's achievement. • If you are not teaching the novel, these materials will support appreciation and study of the play itself. You may want to teach one of Fitzgerald's "cluster" short stories leading up to the novel (see page 3). • With a major film adaptation of the novel also available in 2013, the materials set up comparison of the choices made for each medium. • Units of material include: -- information on Fitzgerald's life, career, and views of the era -- the adaptation choices and the novel itself -- the cultural/historical context of the action -- details about ASF production design, when available About Adapter Simon Levy After directing and writing in San Francisco, Simon Levy has since 1993 been Producing Director/Dramaturg and playwright at Los Angeles's Fountain Theatre, where his work has won awards for directing and playwriting. In the early 1990s he began adapting Fitzgerald's novels to the stage, and now has a trilogy: Tender Is the Night (1995), The Last Tycoon (1998), and The Great Gatsby (2006), all approved by the Fitzgerald estate. 2 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy About F. Scott Fitzgerald, Author of The Great Gatsby Fitzgerald's Major Works 1920: This Side of Paradise (novel), Flappers and Philosophers (short stories) 1922: The Beautiful and the Damned (novel), Tales of the Jazz Age (short stories) 1925: The Great Gatsby (novel) 1926: All the Sad Young Men (short stories) 1934: Tender Is the Night (novel) 1935: Taps at Reveille (short stories) 1941: The Last Tycoon (unfinished novel) One of America's modernist masters of prose fiction, F. Scott Fitzgerald began life amid his family's hardware business in St. Paul, Minnesota. He wrote dozens of short stories to earn money, became a legendary part of the post-war American expatriate community in France, and in the 1930s tried to break into the film industry as a screenwriter for the money. Born in 1896, Fitzgerald's life was shaped by his education in the East, especially his incomplete collegiate career at Princeton, by the woman he loved, his appetite for success and the good life, including alcohol, and his keen eye for his times. Living the adage "write what you know," he adapted his emotional life and the lives of those he met into some of America's greatest 20th-century novels and stories, chronicling the post-World War I Jazz Age and the subsequent Depression with the eloquent scalpel of his pen. Becoming an Author Fitzgerald began writing stories and plays in high school and then proved a better writer of student revues than an academic at Princeton. While there, he wooed wealthy Ginevra King and lost her because he was considered poor, memories which later fed the characters of Gatsby and Daisy. He enlisted in the army during World War I and began his first novel on the new subject of collegiate life. While stationed at Camp Sheridan near Montgomery, Alabama, he met Scott and Zelda, 1923 18-year-old Zelda Sayre. Needing money to win his new love, he worked in advertising in New York City, but Zelda broke their engagement in June of 1919. That July, Fitzgerald returned to St. Paul to revise his novel one more time, and in September he not only got his first short story sale but Scribners accepted the novel. On that basis, he returned to Montgomery for Zelda. Throughout his life he would write "commercial" short stories and pursue screenwriting to earn money and write his novels for art. Fitzgerald as Writer Fitzgerald said his writing grew from an emotional core, so his writing emerges from both autobiography and imagination: "I must start out with an emotion—one that's close to me and that I can understand." The Great Gatsby sold decently in 1925, but not nearly so well as Fitzgerald had hoped. The novel was in abeyance at his sudden death in 1940, but after World War II it had a renaissance, partly due to paperback copies made for the troops, and in paperback it found new readership and renewed critical acclaim to become the masterwork it is considered today. A Fitzgerald TIMELINE • 1896: born in St. Paul, MN • 1911: attends Newman School in NJ • 1913: a freshman at Princeton • 1917: army commission and begins first novel • 1918: July, at Camp Sheridan, AL, meets Zelda Sayre at a dance; novel rejected twice by Scribners • 1919: job in New York; Zelda breaks engagement; home to revise This Side of Paradise, which is accepted • 1920: novel published, marries Zelda; work on second novel, first short story collection published • 1921: first trip to Europe • 1922: publication of The Beautiful and the Damned, move to New York City (1922-24); writes a play that fails; work toward third novel • 1924: to France to write final draft of The Great Gatsby; until 1931, they live mostly in Europe • 1925: publication of The Great Gatsby, begins Tender Is the Night • 1930, 1932, 1934: Zelda's breakdowns; she writes Save Me the Waltz (1932); Zelda institutionalized 1936-40 • 1937-40: Fitzgerald works in Hollywood; dies 1940 3 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy The Novel's Composition Pre-Show: If you are not teaching the novel, having your class read Fitzgerald's short story, "Winter Dreams," a Gatsby cluster story with similar themes, will prepare them for the play and the ideas, themes, and style of the novel's story. As Clifton S. Burhans observes, the story shares with Gatsby "an interesting and often profound treatment of the ironic winner-take-nothing theme, the story of a man who gets nearly everything he wants at the cost of nearly everything that made it worth having." June, 1922—FSF letter regarding early plans for his third novel, which will become The Great Gatsby: "Its locale will be the middle west and New York at 1885 I think. It will concern less superlative beauties than I run to usually + will be centered on a smaller period of time. It will have a catholic element. I'm not quite sure whether I'm ready to start it quite yet or not." July, 1922—FSF letter: "I want to write something new—something extraordinary and beautiful and simple + intricately patterned." In fact, Fitzgerald's practice was to use his short stories to explore his way into a new novel's ideas and themes; critics now call the stories in which he tested material and ideas Fitzgerald's "cluster stories." The cluster stories for The Great Gatsby are: • "The Diamond as Big as the Ritz" (1922) • "Winter Dreams" (1922, which FSF called "a miniature of Gatsby") • "Dice, Brassknuckles & Guitar" (1923) • "Absolution" (part of the 1923 first draft of Gatsby, excised and published separately in 1924) • "The Sensible Thing" (1923-24) October 1922—the Fitzgeralds move to Long Island Arthur William Brown's illustration for Metropolitan magazine's 1922 publication of "Winter Dreams" Right: Villa Marie in Valescure, France, where FSF completed and revised the novel Long Island neighbors: Robert C. Kerr also lived in Great Neck and swapped stories with FSF, telling him about his experience when 14 with E. R. Gilman's yacht on Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn in 1907. Fuller-McGee case (McGee lived nearby on Long Island)—a stock brokerage that went bankrupt due to corrupt practices in June, 1922; rumored to have gambled with investors' funds. FSF later used this case as background for Gatsby's money. Max Gerlach sent FSF a newspaper photo of Scott and Zelda with a written comment that includes the phrase "old sport." June 1923—FSF begins first draft of novel, writing in 12-hour shifts on weekends for three months, interrupted by production of his failed play. This draft, called Trimalchio, was finally published in 2002. April 1924—"Out of the woods at last + starting novel." After spending the fall and winter writing stories to earn money, FSF begins a new draft of novel, discarding 18,000 words (including the part that becomes the story "Absolution"). Now has "a new angle" which may mean a new plot or narrative framework. The Great Neck neighborhood is part of the new angle. May-October 1924: FSF and family move to France, where he finishes this draft of the novel, then immediately begins revising it, rewriting half of it. He writes Max Perkins, his editor: "there's some intangible sequence lacking somewhere in the middle." July 1924— Zelda has a flirtation or affair with a French naval officer. FSF's notebook for September 1924: "I knew something had happened that could never be repaired." November 1924—sends Perkins the typed manuscript (which does not survive). Perkins responds that Gatsby is vague and the long Gatsby biography in chapter 8 might be revealed bit by bit. January/February 1925—FSF revises based on these comments, moving some of Gatsby biography from his chapters 7 and 8 up to chapter 6. About Gatsby he says: "If I'd known + kept it from you you'd have been too impressed with my knowledge to protest…. But I know now—and as a penalty for not having known first, in other words to make sure I'm going to tell more." April 10, 1925—Publication of The Great Gatsby 4 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy What's It All About, Gatsby? • Often cited themes: the American dream money, class, position illusion and reality love and betrayal; marriage and infidelity • "Dream-and-disillusion is Fitzgerald's major theme" (Clifton S. Burhans Jr.) From F. Scott Fitzgerald: • "The sentimental person thinks things will last—the romantic person has a desperate confidence that they won't." (This Side of Paradise) • It's “a story of a world not so much in transition as falling apart without realizing it.” (George Garrett, Fire and Freshness: A • "I'm trying to set down the story part of my generation in America and put myself in the middle as a sort of observer and conscious factor." Matter of Style in The Great Gatsby) From Simon Levy, the novel's adapter: • "I felt like I really got Fitzgerald …. The way he addresses what it means to be a man in American society, the expectations and pressures, the mythology attached to that; and especially what it means to be an artistic man trying to be successful in this culture." • "There's no question that it's about the American Dream.…We like to pursue the unattainable.… You see all sorts of layered ideas, about doomed love, and betrayal; about perceptions of illusion and reality; about seeing; about class. There's greed and heartlessness in it, and there's the whole issue of time…." "[Fitzgerald] writes about the broken parts in men in a way that I've never encountered in any other writer." • "Life was something you dominated if you were any good." ("The Crack-Up") • "That's the whole burden of this novel—the loss of those illusions that give such color to the world so that you don't care whether things are true or false as long as they partake of the magical glory." (FSF letter to a friend, August 1924) • about the Jazz Age: "It was an age of miracles, it was an age of art, it was an age of excess, and it was an age of satire." "A whole race going hedonistic, deciding on pleasure." "It ended [in 1929], because the utter confidence which was its essential prop received an enormous jolt, and it didn't take long for the fliimsy structure to settle earthward.… It was borrowed time anyhow—the whole upper tenth of a nation living with the insouciance of grand ducs and the casualness of chorus girls." ("Echoes of the Jazz Age," The Crack-Up) Biographical Elements in Gatsby Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Sayre about the time they met in 1918. He had just dropped out of Princeton to enlist, and she had just graduated from high school. FSF quote at right from "Pasting It Together" in The Crack-Up F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote from emotional truth, usually his own, though his artistic insights went far beyond the personal. In terms of Gatsby and Daisy, Fitzgerald drew on his first two loves—the first, Ginevra King, whom he met when she was 16 and he 19, seemed the ideal girl, "beautiful, rich, socially secure, and sought after." He felt she was the girl he loved and lost because she was wealthy and he was "poor" by comparison. Ginevra married into a very wealthy Chicago banking family in 1918. Jordan Baker is based on one of Ginevra's friends, golfer Edith Cummings. His next love was Zelda Sayre, another socially prominent young girl whom he did not have the money to marry; in fact, she broke their engagement when he did not succeed fast enough. He gambled on his first novel, which he re-wrote back at home that summer of 1919: During a long summer of despair I wrote a novel instead of letters, so it came out all right, but it came out all right for a different person. The man with the jingle of money in his pocket who married the girl a year later would always cherish an abiding distrust, an animosity toward the leisure class—not the conviction of a revolutionist but the smoldering hatred of a peasant. In the years since then I have never been able to stop wondering where my friends' money came from, nor to stop thinking that one time a sort of droit de seigneur might have been exercised to give one of them my girl. He won Zelda; then in the summer of 1924 while writing the novel felt they'd lost their trust when she flirted (or more) with a French officer. His life nourished his novel; his artistry made it great. 5 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Pattern and Character in the Novel and the Play Character/ Major Arcs of Action Growth/change: Nick Carraway, Jay Gatsby (especially in past; is he still changing?) Pursuit of dream: Jay Gatsby, Nick Carraway, Myrtle Wilson Choice of dream: Daisy Buchanan (in past and present—love vs. money) • Compare/contrast Nick and Gatsby and their quests for money and love. • In chapter 8, Gatsby tells Nick about meeting Daisy, which is narrated indirectly: However glorious might be Eckelburg's eyes as Myrtle is killed in the 2013 film Compare/Contrast: • West Egg and East Egg; Gatsby's and Tom's homes • first meal at Buchanans' home to "showdown" meal • parties (the two Nick narrates at Gatsby's, and those to Tom's in his NYC apartment) • escapes to NYC (to apartment and to Plaza Hotel) • the relationship triangles : Tom/Daisy/Gatsby vs. Tom/ Myrtle/George Wilson. What is their basis—love? sex? dream? How does Nick's developing relationship with Jordan compare to these? • reaction to "infidelity": Tom's, George Wilson's, Gatsby's • success at football vs. success in war; also a football past and polo present Assessing Gatsby's Goal • Gatsby believes one can repeat the past, go back and make it right, become that person again and take another path. Why do we want another chance or another choice? Why do we not accept the past as "past," final? Is it? Can we change the past from the present? his future as Jay Gatsby, he was at present a penniless young man without a past, and at any moment the invisible cloak of his uniform might slip from his shoulders. So he made the most of his time. He took what he could get, ravenously and unscrupulously—eventually he took Daisy on one still October night, took her because he had no real right to touch her hand. (emphasis added) How apt is Fitzgerald's description of Gatsby's approach to what he wants? (Does it also describe Tom?) And in terms of dreams or the American dream, who has a "right" to success and love? Are they a matter of "right"? What is the basis of that "right"? Who decides and why? • Does Daisy actually make a choice in the past or in the present? Points of Origin Nick, Gatsby, Daisy and Tom, and Jordan may all be living in New York City in the summer of 1922, but they all are from the Midwest: Nick from Minnesota, Tom from Chicago, Daisy and Jordan from Louisville, Kentucky, Gatsby from North Dakota. • Fitzgerald makes a point that they are all from the "West." What does that mean to him and to the story; what is the contrast of West and East in values? in the tradition of American culture? War Service Overseas service in World War I: Jay Gatsby, Nick Carraway Not in war: Tom Buchanan, George Wilson Money Who has money: Gatsby, Tom, Meyer Wolfshiem Who wants more money: Nick, Myrtle Wilson • Nick walks away from the East and the lure of money. How important is money in this story? Does it matter how it's made? Class and Status Upper class: Tom and Daisy Buchanan, Jordan Baker Nouveau riche: Jay Gatsby, Meyer Wolfshiem "Well-to-do"(family in hardware business): Nick Carraway Working class: George and Myrtle Wilson Homeowners: Jay Gatsby, Tom Buchanan (huge houses with lots of staff) • How is class different from money? How does the difference work in the story? How does Fitzgerald value money and class? Love and Marriage Married: Tom and Daisy Buchanan, Myrtle and George Wilson Having affairs: Tom Buchanan and Myrtle Wilson, later Gatsby and Daisy Buchanan Dating and more: Nick Carraway and Jordan Baker • What role do fidelity and infidelity play in the novel? Who is faithful; to what and why? • Many critics observe that this novel is one of the first not to "punish" wrongdoers (crime or vice). Why not? Does the story judge? Vocations and Avocations Working: Nick Carraway, Jordan Baker, Jay Gatsby, Meyer Wolfshiem, George Wilson Not working: Tom and Daisy Buchanan, Myrtle Wilson Sports figures: Jordan Baker, Tom Buchanan Writer: Nick Carraway, working in Wall Street • What role does work play in the story? Not working? Significance of Nick in "bonds"? • Compare warfare to the sports drive to win. Alcohol Drinkers: Tom and Daisy Buchanan, Jordan Baker, Nick Carraway, Myrtle Wilson Non-drinkers (or very seldom): Jay Gatsby • What role does alcohol play in the story? Cheats, Crooks, and Murderers Cheats: Jordan Baker, Tom Buchanan Crooks: Meyer Wolfshiem, Jay Gatsby Murderers: George Wilson, Daisy Buchanan "Honest": Nick calls himself honest; is he? Sense of honor, chivalry: Jay Gatsby, George Wilson (justice or revenge?) • How does the story judge crossing the lines of established law and morality? 6 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Considering Tragedy and The Great Gatsby Gatsby's mansion in 2013 film The Eyes Have It Critics unanimously see T. J. Eckleburg's billboard with its huge eyeglasses and staring eyes as a dominant symbol in the novel, overlooking as it does the Valley of Ashes and the first death in the climactic sequence. In his stress and grief, George Wilson seems to equate them with the eyes of God—or perhaps the two are simply juxtaposed, one on earth and one in heaven. But what, one might ask, do painted eyes "see"? Is their significance more that they seem to look but do not see? Who or what else looks or judges without seeing in the story? How do we expect God to see and judge? Eckelburg's eyes from 1974 film The other set of eyes that seem all-seeing in the story are Nick Carraway's, for he sees and/or hears details no one else does and shares with us perspectives no one else has. He calls himself "within and without," and he puts us there as well. Nick's eyes and narration are Fitzgerald's great gift to the story. How does he see and judge? The novel, and hence the play and/or film based on it, is considered a tragedy—the tragedy of one man, or more, perhaps also the tragedy of an era and lifestyle or even of American society itself. In studying tragedy, one looks for the tragic protagonist and his or her recognition of the tragic events and also acceptance of responsibility for them. One looks for the point-of-no-return in the action, the moment or choice that makes disaster inevitable. One also looks for the tragic insight, for some characters cause and embody the tragedy while other characters may survive and articulate it (think Edgar and Albany in King Lear or Horatio in Hamlet). So what is the point-of-no-return in The Great Gatsby? Gatsby's death, if death is the tragic event, is a direct result of Daisy's hitting Myrtle while driving Gatsby's car—and of everyone making assumptions about who the driver was because Gatsby's sense of honor makes him take the blame in a cabal of silence—Daisy doesn't tell Tom, though Gatsby tells Nick, and Nick only tells the reader. To what extent does "Daisy drives Gatsby's car" function as an image or symbol of the action of the novel? Who or what "drives" parts of the action and what the "drives" are in the story are crucial to our understanding of the tragedy. Myrtle only runs out to stop the yellow car because she saw Tom Buchanan driving it into New York City earlier in the afternoon. Tom had actually tried to drive Daisy in Gatsby's car as a male dominance tactic when he felt threatened, but instead Daisy went with Gatsby in Tom's car. Who's driving whom in what may have significance in the relationship crisis as well, for the Tom/Daisy/Gatsby triangle is now pressurized, and one side of it is collapsing. Myrtle is pressured by George's discovery of the dog collar (another potent image: is she like a dog to him?) and by his determination to leave—so later when she sees the yellow car returning, she wants to believe Tom has come back for her; she wants to escape Wilson and that life. We know it is a false hope because Tom in his noblesse oblige is a serial philanderer, and at the moment he is more concerned with Daisy. Is Myrtle's death incidental to the larger tragedy, unfortunate but not important, or is it part of Tom's role as antagonist? Daisy as driver is caught between oncoming traffic in the other lane and this stranger running into her lane. She swerves one way and then she swerves back. Does she choose whom to hit or does she panic? Gatsby says that at the last minute his hand is also on the wheel, trying to avoid calamity; does he help or not? And can we read that part of the incident in larger terms—Daisy wants to run away with him, but he wants a confrontation with Tom and victory in the eyes of the world. Instead he gets a fatality under the eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg. They would not be on that "road" at that time were it not for Gatsby's need to re-route the past. Does hitting Myrtle cause the end of Daisy and Gatsby; is it the "fatal" event for the protagonist and his dream, or has that event already happened? Did Tom's revelation of the source of Gatsby's money doom the affair in Daisy's eyes? Gatsby has made a fortune to win Daisy, and Tom then redefines the nature of the quest—it's not having money but what kind of money you have. Tom's money is "old money" by American standards, inherited perhaps from robber barons or manipulative bankers several generations earlier, but now socially sanitized. Gatsby's lucre is shiny new and gaudy, like his lifestyle and car. Yes, he has money, but Tom suggests he has "only" money, not the social cachet important in high society. Is the showdown between Tom and Gatsby for Daisy the cause of the disaster, or is the point-of-no-return even earlier? Is Gatsby's insistence on having Daisy and having the past recreated in the present, rewriting what had happened ("she never loved you") the cause of his disaster? He has her, but only in the present; he still "lost" her in the past. Or is that past moment five years ago the actual cause of the tragedy, the point-of-noreturn? Daisy falls in love with Gatsby in uniform (when men are "uniform"). Does that matter? When Gatsby first kisses Daisy, he describes a crisis in his quest—he knew his upward climb at that point embodied or incarnated itself in Daisy, no longer in himself. What does that mean to Gatsby's love and/or need for Daisy? Does he love this woman or does he need what she symbolizes to him? Debate the point-of-no-return and the fault or mistake that make Gatsby a tragic protagonist. And what does Nick see and think? 7 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy A Novel versus a Play—What Happens in Adaptation Carey Mulligan and Leonardo DiCaprio in the 2013 film of Gatsby Novel • narration/ commentary • description and imagery • reader's imagination meets author's portrayal Play • live characters in action • impressionistic visuals (not realism) Film • spectacle and large crowd scenes • opulent visuals and detail • camera makes choices with its own cinematographic style and pace Literary critics agree, in fact, acclaim, that what makes The Great Gatsby a brilliant novel is not necessarily its story but the way it tells its story—that the structure and especially the narration set the novel apart from previous fiction and make it modern and exceptional. Thus Nick Carraway's voice, his perspective, his various ways of seeing and recounting events, his own sensibility exploring Long Island and New York alongside Gatsby, his own impressions of the society and lifestyle, his own response to the pace and promise of life as juxtaposed to Gatsby's all make the novel what it is. The actual events of the novel, its bare bones plot, is so wrapped in Nick's sensibility that how we know is also in large part w h a t w e k n o w. This technique is a strength of the novel, where sensibilities can emerge and evolve over time as the pages turn. The Medium Is the Message On stage or on film, the medium works quite differently, and that difference is one reason a great novel such as Gatsby is so difficult to record on film and why a stage adaptation inevitably diverges from the experience of the novel. A film is visual and seen cinematographically—not by means of a narrator but by means of a lens, quite another perspective than the words of Nick Carraway. What we imagine about Gatsby's parties in the novel we are shown in a film, and in its three filmic treatments, the approach has been excess on another scale than Gatsby's. On stage, character and action drive the drama—conflict must be defined and active early on. The mystique of Gatsby for Nick and of Daisy for Gatsby consume more than half the novel, but on stage much of that narrative angle is omitted, and we move scene to scene, action to action, which gives us a very different sense of what the story is and what it may mean. The novel is Nick's story of Gatsby; the play becomes for the most part Gatsby's story, even if a few passages of narration are included. Nick's sensibility can never shape the action on stage the way it does in the novel. The Novel and the Play Chapter Text/ Action Play 1 • Nick's introduction; first trip to Buchanans; Act One meets Jordan, Daisy hears Gatsby's name; phone calls; Gatsby looking at green light 2 • Tom takes Nick to meet Myrtle in NYC 3 • Nick to Gatsby's party, meets Gatsby; sees more of Jordan 4 • those attending Gatsby's parties; lunch --straight to lunch and with Gatsby; Jordan's story of Gatsby story, flashback scenes and Daisy in 1917; makes invitation 5 • at tea party, Gatsby meets Daisy again; shows her his house 6 • Gatsby's background/name change; Dan Act Two Cody story; Tom stops at Gatsby's, comes --Tom only at Gatsby's to party with Daisy; what Gatsby wants now with Daisy at party 7 • lunch at Buchanans, go into NYC; showdown at Plaza; Tom's verbal attack on Gatsby; drive home, accident, and aftermath 8 • Gatsby about Daisy; aftermath at garage --very compressed and Wilson to Gatsby's house background 9 • funeral and last sightings of Jordan and --just mention of funeral; Tom; Nick's last meditation on Gatsby meditation 8 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy The Novelist and the Playwright: What Is Essential What Is the Essence of The Great Gatsby? Critics agree both on the greatness of the novel, that is, its importance in the American tradition, and on the basis of that greatness— • “In terms of form, then, more than anything else, in terms of style, Gatsby is a pioneering novel.” —George Garrett, "Fire and Freshness: Can we get the essence of Fitzgerald's genius in any form except his novels and stories? Can his work be staged or filmed?—those are the questions. What Sparks Adaptation In coming to theatrical adaptation, Simon Levy says he had a "conversion experience" on a trip to Russia in 1989, where he realized a great story there was regularly translated medium to medium, novel to ballet to film. "Each medium has its valid form of expression for the same story," which is accepted and treasured in that culture, Levy recognized, but somehow has been devalued in America, though this is changing. Sources for Quotations: • F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: A Literary Reference, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli • Guthrie Theater interview (pp. 4-10): http://qgaby.tripod.com/ sitebuildercontent/ sitebuilderfiles/thegreatgatsby. pdf • Arizona Theatre Company interview: http://www.arizona theatre.org/ inside/atc/newsletter-archive/ no.-3-spring-2012/ show-related/ 410/3033/ • Prime Stage interview: http://www.primestage.com/ shows_and_tickets/simon_levy. html A Matter of Style in The Great Gatsby" • "… much of the effectiveness of Fitzgerald's stories depends on elements of style and narrative technique that cannot be transferred to the stage.… A Fitzgerald story or novel in dramatic form loses many of the qualities that make it a Fitzgerald work…." —Matthew J. Bruccoli, Some Sort of Epic Grandeur [FSF biography] • “Compression [of the novel to its plotline] dispels the aura of tragic mystery in which Fitzgerald envelops his hero.” —Kenneth Tynan, "Gatsby and the American Dream" • “For what is Daisy, dreadful Daisy, but his dream and the American dream at that? … Vapid, vain, heartless, self-absorbed, she is still able to dispel a charm the effect of which on Gatsby is simply to transform him into a romantic hero.” —Louis Auchincloss, "A 'Perfect Novel'" The Essence of the Novel as a Play The Fitzgerald estate had enough concern about translating The Great Gatsby to the stage that it did not initially grant Simon Levy permission to adapt the novel. The estate did, however, with approval rights, allow him to adapt Tender Is the Night, which premiered in 1995, and then The Last Tycoon in 1998, telling him to finish this story Fitzgerald left incomplete at his death. At last Levy was given rights to adapt Gatsby, which premiered in 2006 at the new Guthrie Theatre. In interviews, Levy discusses the task of adapting this novel: • "… the central question has always been: 'How do I use the language of theatre (the 'plastic elements' …) to honor the beauty of Fitzgerald's prose?'" [So he looks for ways to use the novel's symbols in dialogue or production elements, substituting scene design, lights, and/or sound for narrative elements] "One of the great advantages of theatre is how we are able to give life to symbolism and metaphor on stage. As an art form we excel at being suggestive rather than literal. It's what we do best." • "But the language of theatre is not about prose.… The language of theatre is dramatic. You have to find a way in dialogue to get to the conflict.… The stage is not as forgiving.… You have to stay with the through-line." And "there was the question of Nick. How do I make him active?" Finally, "he's the character I have the deepest affection for…. It's ultimately his journey, his eyes through which we see…." • "What often happens with iconic novels … is that we romanticize them.… We fall in love with style and form. We forget that great stories are about great characters caught up in great plots. At the heart of this novel is adultery, betrayal and love.… As important as Form is to this novel and this stage presentation, it's the Content that we will always carry with us, a remembrance of great and singular characters!" • "I've felt the need to open [the characters] up dramatically in a way that isn't always necessary in the novel." • "It's really essential that the piece be fluid, that this be a dreamscape, where thing and people float in and out, like the hazy gossamer language of Fitzgerald. Then, there are the 'hard' scenes—when you see the ugly side of people, the more traditionally dramatic scenes where there is hurt and love and betrayal and the complexities of being human. I want that world to crash up against the dreamscape world, so that we're seeing the clash between illusion and reality." 9 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Making The Novel into a Play—Thinking Like an Adapter A Worksheet for Those Teaching the Novel: The Role of the Narration In adapting The Great Gatsby for the stage, Simon Levy decides to include some of Nick Carraway's narration—a bit of the opening and some of the ending, with a few moments in between. No Nick Carraway would not be Fitzgerald; all the Nick Carraway would make it another kind of play entirely, almost a oneman show. But how does one cut Fitzgerald's narration down to the bare essentials? • What, in your opinion, is essential in the narration? What must be included? Nick (Tobey Maguire) and Gatsby (Leonardo DiCaprio) watching the show at a New York speakeasy in Luhrmann's 2013 film. Titles Fitzgerald Considered for the Novel • Among Ash-Heaps and Millionaires • On the Road to West Egg • Gatsby • The Great Gatsby (an early suggestion and his editor's favorite, which Fitzgerald thought "only fair") • Trimalchio (a nouveau riche Roman satirized for his elaborate feasts in Petronius's' Satyricon, c. 66 C.E.; his editor thought the allusion too obscure) • Trimalchio in West Egg (FSF's choice for title) • Gold-Hatted Gatsby • The High-Bouncing Lover (both of these are from the verse epigraph Fitzgerald wrote for the novel) • Under the Red, White, and Blue (FSF's last suggestion) • How important are Fitzgerald's first three sentences of the novel? What is important in them? Levy includes these three sentences. They offer us: 1) the idea of "criticizing"— who and what does the novel set up for criticism? who or what is criticized by other characters? who or what does Nick criticize? do those criticisms all agree? 2) having "advantages"—how important are "advantages" and what "advantages" does Nick's father believe Nick has had? who else in the novel has had "advantages"? what kind? how do the various kinds of "advantages" affect the various kinds of "criticism"? how are those two concepts linked in the novel? 3) "he meant a great deal more"—Nick's father is reserved. Is Nick also reserved in his narration? Does he mean a great deal more? Does anyone else operate that way? Levy uses three more sentences from Nick's introductory section (the first two pages of the novel). Which three sentences would you choose as the most important to set up the story? Justify your choices. Evaluate Levy's choices and edits, which are: Gatsby, the man who gives his name to this story, represented everything for which I had an unaffected scorn. But if personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something … gorgeous about him … some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life. He had an extraordinary gift for hope, a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person… and which it is not likely I shall ever find again. • Levy displaces the last sentence of Nick's introduction to the transition from the first luncheon scene to the first Valley of Ashes scene. He edits this sentence as well, which actually stems from much earlier in the paragraph when Nick says "I wanted no more riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart." Consider the implications of the changes: Fitzgerald: No—Gatsby turned out all right at the end; it is what preyed on Gatsby, what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreams that temporarily closed out my interest in the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men. Levy: …what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreams that's been haunting me… and haunts me still. • How important are Nick's own responses to being in New York City? What promise or response does he feel? Should they be included? If so, what part? • What part of Nick's recognition of and responses to Gatsby's dreams and pursuit of them should be included? Pick your passage(s) and justify why. Consider what Levy chooses and compare. • In selecting short passages from the end of the novel, Levy makes the dramatic choice to have Nick's assessment of Tom and Daisy delivered as direct address to their oblivious figures ["They were careless people…" becomes "You're careless people"]. Explain how the play's use of dialogue may have an effect quite different from the novel's. After that passage, which occurs the last time Nick sees Tom Buchanan, the next sentence in the novel is "I shook hands with him; it seemed silly not to…," while Nick's next sentence in the play is "I couldn't forgive any of them." Assess the power of each choice.. • The last two paragraphs of the novel are presented intact. Why might that be a good artistic choice? 10 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy The Adaptations: Plays and Films Alan Ladd and Betty Field in the 1949 film Robert Redford in the 1974 film Leonardo DiCaprio and Carey Mulligan in the 2013 film America attempts to capture The Great Gatsby on stage or film once every generation. It hit the stage immediately after publication, for in 1926 a "clumsy" stage play found power in live action, but tweaked the plot to make Myrtle the wife of Tom's chauffeur, who discovered his wife's murderer based on a cigarette holder. The 1949 and 1974 Films In 1949 the big screen saw Alan Ladd and Betty Field try to "clarify" the novel, letting Gatsby realize Daisy had betrayed him just before he was shot. This film also had to deal with the censorship issue: the film "dealt with unpunished adultery, unpunished manslaughter, and an unpunished moral accessory to a murder. And yet 'The Great Gatsby' is in essence a modern morality play depicting irresponsibility leading to catastrophe," or so the filmmakers argued. Director Richard Maibaum created a prologue of Nick and Jordan, now decent and humble, standing over Gatsby's grave and looking back on the 1920s, and he gave Gatsby a Biblical quote on his tombstone: "There is a way which seemeth right unto a man, but the ends thereof are the way of death" (Proverbs 14:12). Then in 1974, Robert Redford, Mia Farrow, and Sam Waterston took on Gatsby, Daisy, and Nick in a film that became a marketing extravaganza; many reviewers felt the p.r. crushed the film. The New York Times review decreed "the movie itself is as lifeless as a body that's been too long a the bottom of a swimming pool" and blames "the all-too-reverential attitude" that thinks the greatness of the novel is in the story rather than its style. Farrow was widely panned for her portrayal of Daisy. Luhrmann's 2013 Film In 2013, Baz Luhrmann's extravagant Gatsby film hit the nation's screens with the stylistic flair (or overkill) of his previous films such as Strictly Ballroom, Romeo + Juliet, and Moulin Rouge. The official website describes the film as "weaving a Jazz Age cocktail faithful to Fitzgerald's text and relevant to now." The film's techniques—including 3D, self-conscious camera work (zoom shots, slow motion, hideand-seek mystery shots), and huge production numbers at Gatsby's parties give it definite "excess" and build on Fitzgerald's description of New York as a "splendid mirage." These elements join the twisted fairy tale aura of Gatsby's castle/house and Nick's cottage (architecturally based on the garage in which FSF first drafted the novel in Great Neck). Luhrmann highlights Nick's narration by creating a new backstory—that after Gatsby's death Nick cracked up, is now being treated for alcoholism in a sanitarium where a doctor (also created) encourages him to write, which he does. We see him typing, we see the pages pile up, and at the end we see him title the completed work. While others may not change, Nick does, the screenwriters feel—the innocent writer sees into the dark heart of the world of wealth he thought he wanted. In discussing Gatsby, DiCaprio calls him "very much the manifestation of the American dream, of imagining who you can become … and he does it all for the love of a woman. But even that is open to interpretation: Is Daisy just the manifestation of his dream? Or is he really in love with this woman? I think that he's a hopeless romantic but he's also an incredibly empty individual searching for something to fill a void in his life." Luhrmann and others praise DiCaprio's ability to capture "Gatsby's dark obsession, his absolutism." Comparing Film and Stage Adaptations • Film uses visual detail, in the case of Luhrmann's 2013 film, even visual excess in both setting and technique. Levy's stage adaptation uses suggestion, not a complete stage world of detail. What is the effect of each kind of choice on the story? • Compare the treatment of the overall work and of the major characters in the 2013 film and Levy's stage adaptation. What does it mean to try to be true to Fitzgerald's novel in another medium? 11 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Geographic Orientation for The Great Gatsby The Corona dumps, a.k.a. the "Valley of Ashes" Below, an ash mountain in the dump (note the person on top for scale) F. Scott Fitzgerald lived in Great Neck on Long Island, New York from 1922, just after he began planning his third novel, which would become The Great Gatsby, until 1924, when he and Zelda moved to France as an economizing measure, and there he wrote and revised the final draft of the novel. His fictitious East Egg and West Egg are based on the east (Manhasset) and west (Great Neck) shores of Manhasset Bay. He has the geography and social strata right for each side—east was old money, west was show business and new money—but he changes the names. He also accurately describes the "valley of ashes," a swampy area on the Flushing River used for dumping New York City's garbage, horse manure, andashesfromcoal-burning furnaces. The ashes were piled into plateaus, and both the road from Great Neck and the railway headed to Queens and Manhattan cut across this dump, though not as close to each other as Fitzgerald describes. This area was redeveloped for the 1939 World's Fair, the ashes used in the foundation of the Van Wyck Expressway, and it is now Corona P a r k / Flushing Meadows where the Mets play at Citi Field. In New York City, his choice for the confrontation between Tom and Gatsby is the Plaza Hotel at the south e n d o f C e n t r al Park, famous for its elegance. Map of the novel's sites from F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: A Literary Reference, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2000). The circle indicates the Valley of Ashes area. The Plaza Hotel, New York, at center right 12 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Long Island's "Gold Coast"—The Mansions of the Novel On Long Island, twenty miles from Manhattan, along the shore of Long Island Sound, the now very wealthy 19th-century industrialists (the so-called robber barons) and bankers built their mansions on the "Gold Coast," joined by the newly wealthy and the glitterati of show business. The names—to give a short list of the sort Fitzgerald satirizes at the top of chapter 4—include the Astors, the Vanderbilts, the Phipps, several Guggenheims, the Belmonts, the Fricks, as well as George M. Cohan, Groucho Marx, Basil Rathbone, Edgar Selwyn, and Ring Lardner, with Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald renting a house near the head of Manhasset Bay, where they were neighbors to newly rich bootleggers. Famous "Gold Coast" mansions: above, Beacon Towers, August Belmont's mansion, demolished in 1945, which is widely thought to have influenced Fitzgerald's description of Gatsby's mansion. Right, The Braes, Herbert L. Pratt's estate, built 1912. Below it, a 1920s' cartoon, "Summer Shack of a Struggling Young Bootlegger," testimony that Gatsby's career is far from uncommon in the Prohibition era. Below left, Lands End, which was recently demolished, Fitzgerald's supposed source for the Buchanan home on Long Island. 13 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy The steady rise, sharp spike, and sudden fall of the 1920s' Stock Market, using the example of one share of GE stock "Everybody calls me a racketeer. I call myself a businessman. When I sell liquor, it's bootlegging. When my patrons serve it on a silver tray on Lake Shore Drive, it's hospitality." —Al Capone, head of the Chicago mob All quotations from Time-Life's This Fabulous Century/ Volume 3: 1920-1930. The Historical Context, Part 1: The 1920s as the Boom The decade following America's brief involvement in World War I marked a stunning shift in values and lifestyle for many Americans. The war shook up the country, and, as in Europe, suddenly the old ways were finished and a host of new ideas took root. On the World Stage America's role in World War I put it at the center of the world stage, ready to assume leadership. The long history of U.S. isolationism was not so easily overcome, however. America was late to enter the war, just as it would be in World War II, and though the Spanish-American War had signaled the country's entry to world affairs, the U.S. was not yet willing to accept the responsibility such presence entailed. In the 1920s America again grew isolationist, as Woodrow Wilson's defeat in the 1920 election showed its lost faith and its feeling that perhaps the war had not been worth the sacrifices. Politically, economically, and socially, America was unsure about the changes it was rushing into and preferred to ignore their implications. The Economy The 1920s' New York of The Great Gatsby centers on money. New York was the largest city in America with its 5,620,000 inhabitants in 1920 and attracted those interested in making money. Wages and disposable income increased, so that more Americans could buy new household goods on the installment plan. Wall Street went on a decade-long wild ride, soaring high and sucking more and more modest investors, lured by its quick gains, into its maw by letting them buy with only 10% down and the rest on loan. All of that ended, of course, in late October, 1929, when the market crashed, the loans came due, and the big boom led to the big bust of the Depression. The Crash revealed the truth that the economy was and had been unsound, that banks and corporations had been undermined by fraud, that trade policies were unproductive, and that a comparative few had been profiting on the backs of the many. Prohibition On January 20, 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution went into effect declaring the manufacture, sale, furnishing, or transportation of intoxicating liquor to be illegal (but not private ownership or consumption). The law proved to be unenforceable, not only due to the rise of very successful bootleggers or to the consequent emergence of gangsters and organized crime in the United States ready to profit from such illegal activities. Many Americans simply chose to break the law and drink anyway. Ritual wine was legal, and many suddenly became very devout, and doctors could prescribe alcohol for "medicinal purposes," the need for which suddenly abounded. But most didn't bother and just purchased bootleg liquor. The wealthy had stockpiled alcohol before the ban went into effect, so the law mainly impacted the poor. Whereas women had been banned from saloons before World War I, in the Prohibition era women frequented speakeasies, the underground saloons of the 1920s, to imbibe the new drinks, cocktails. By 1925, New York City may have had as many as 100,000 speakeasies, all helped along by paying off the cops and those in "protection." People also began to drink at home and even make their own liquor with a portable still. Racism The 1920s saw a resurgence of racism in America. Not only were times still hard for many farmers, coal miners, and textile workers, they were also extremely difficult for black sharecroppers. In addition, the Ku Klux Klan rebounded to more than 4 million members by 1924. Prejudice also extended to immigrants and their political views, as the Sacco-Vanzetti case demonstrated. Thus, the escapism of the 1920s proved impossible, and perhaps they knew it. "Even among the most frivolous there was an air of desperation," we are told. "Behind the bright surfaces of the '20s … lay an abiding sense of futility." Working with the Story • Money plays a major role in the story. What kinds of money does Fitzgerald show and how does it work; how isolationist is it; how is it judged? What is Fitzgerald's view? • Alcohol flows plentifully though the story, despite Prohibition. Consider the idea of what else is "prohibited" in the story, what "prohibitions" are ignored or transgressed. How does Fitzgerald portray "prohibition" and to what end? • The play includes the detail that Tom Buchanan is an avowed racist. Why does he have such views? Real book is Lothrop Stoddard's The Rising Tide of Color against White World-Supremacy (1920). 14 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Covered, corseted, and bustled, the pre-World War I lady wore a formidable array of fabric and a "Merry Widow" hat, and always wore gloves out of doors, while the flapper (here sketched by John Held), by comparison, was uncovered, uncorseted, and as free in manners as in clothing, which was made of synthetic silk accessorized by synthetic pearls, and topped by bobbed or shingled short hair. The Historical Context, Part 2: The 1920s as the Jazz Age The Jazz Age is famous for its desperate gaiety and its romantic cynicism. Hedonism abounded, movies promised the good life to 90 million viewers a week by 1930, and America, especially young America, craved excitement. Yet the jazz of the Jazz Age, the club scene, the iconic flappers and college boys are not really a part of Fitzgerald's third novel. He alludes only to popular tunes used for the lyrics' ironic relevance—"Ain't we got fun" or "I'm the sheik of Araby / And you belong to me," sheik being 1920s' lingo for a young man with sex appeal—like film star Rudolph Valentino, whose slicked down hairstyle Fitzgerald and many others copied. "Jazz" was shorthand for the lifestyle changes seen in the 1920s in both consumerism and sexual mores—"America," it was said, "was going on the greatest, gaudiest spree in history," and it would pay the price. Watch the Women Every generation believes it is the first to discover human sexuality, but the 1920s may have a legitimate claim to the advertising and accessibility title for sexual exploration when compared to many previous generations. The double standard had been perfected, though not invented, by the Victorians, with the wife, the "angel of the house," often kept as protected and ignorant as her children concerning the real world. In daily life of the pre-World War I world, women's bodies were almost completely covered and restrained by garments and undergarments and their lives overseen by their elders or chaperones. Proper young women were not informed about human sexuality and often went to their honeymoons knowing perhaps only a chaste, chaperoned kiss or hand squeeze in the name of ardor. (One should also note that the double standard of the Victorian era also led to London's having the highest rate of prostitution in the world.) In cities, post-World War I American women proved to have decidedly different ideas about both fashion and behavior. Hemlines rose throughout the decade of the 1920s, but the flapper stereotype (see left) is actually true only of 1926-1927, after the novel's publication, though the lifestyle and attitude changes associated with rising hems were apparent earlier. Sexual Mores In the 1920s, as never before, women drank with men and smoked with men. They rejected the double standard and decided to have just as much fun as the guys did. Since morality has always landed harder on "daughters of Eve," this new openness and frankness about women's sexuality was part of the culture's modernism, embracing new psychological views (though Freud never did figure out what women want), the new political voice of women's suffrage, and new consumerism. For the men's part, their readier access to automobiles made sexual exploration far more interesting and available. Women were now not always chaperoned, and driving led to parking, and parking led to sexual adventures in the back seat, as countless jokes and cartoons from the 1920s attest. A John Held cartoon of 1920s' wooing Working with the Story • Romantic cynicism, hedonism, a spree, desperation, futility—how and where do these generalizations about the 1920s appear and work in Fitzgerald's story? How does he use them? Is he more cynical than his 1922 setting? • Love and sexual mores are crucial concerns in Fitzgerald's novel. Tom and Daisy are married, but Tom regularly has affairs. His current affair is with Myrtle Wilson, a married woman of lower status. Gatsby has long loved Daisy, and their relationship seems to develop into an affair during the summer of the novel's 1922, as does Nick Carraway's dating of Jordan Baker. How do the characters view and value these relationships, and how does Fitzgerald compare and contrast them? What are the story's values and view of love? marriage? 15 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Talkin' the Twenties baloney iled ard-bo h ra m sc spiffy fall guy knees the behe's orsefeather big cheese y gol lous y dd w e r igg sccar er ritzy s ry a to rch whoopee The Jazz Age was driven by youth culture, an emphasis that made Fitzgerald's first novel, This Side of Paradise—about collegiate life, including binge drinking and "petting parties"— his best-known novel for his contemporaries. Fashions changed, and soon skirts, like hair, were bobbed short, the better to dance the Charleston. Guys drove their new cars and enjoyed their opportunity for privacy. And where youth led, many in the older generation followed. In a fast-paced age that had read Freud in English for the first time and was challenged by Einstein's theories, being modern meant leaving Victorian values and world views in the dust. While the vast and pious middle of the nation made no such sudden shift, New York City was the epicenter of this cultural movement. Uptown, Harlem's black nightclubs introduced white visitors to jazz and the music of Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, and Louis Armstrong. "Race records" let them buy the music of black artists and play it at home or hear it on the radio. Downtown, Wall Street kept making money, and in the '20s having money meant spending money. Even the language of the '20s changed, as youth found their own inventive words to scorn stodgy old ways—they were b a l o n e y, h o k u m , horsefeathers—and to imprint the new— which were swell, spiffy, the bee's knees. Many of the terms still live in our parlance, though we may not realize their roots are in the Jazz Age. Spiffy gold digging— cartoon by John Held, Jr., whose graphics expressed the Jazz Age Have You Heard These Jazz Age Terms? • being all wet—being wrong in a belief • baloney—nonsense • it's the bee's knees—something superb • belly laugh—big, uninhibited laughter • Bible belt—coined by H. L. Mencken, an area in the South or Midwest dominated by Fundamentalist religion • blind date—a date with a stranger usually arranged by a mutual friend • big cheese—an important person • bull session—informal group discussion • bump off—to murder • bunk—nonsense (shortened from bunkum) • carry a torch—have unrequited love • the cat's meow—something wonderful • crush—an infatuation with someone • fall guy—scapegoat • frame—to give false evidence to get someone arrested • gatecrasher—someone who attends a party uninvited or who does not pay admission • gold digger—a woman who uses her charm to get money from a man • goofy—silly • gyp—to cheat (a slur, from gypsy) • hard-boiled—tough, unsentimental • horsefeathers—nonsense • kiddo—a familiar form of address (like we use guy) • kisser—the mouth • line—insincere flattery • lousy—bad • main drag—most important street in town • neck—to kiss and caress • pet—same as to neck • pinch—to arrest • ritzy—elegant (from the Ritz, a Paris hotel) • the real McCoy—the geniune article • the run-around—delaying action, especially to a request • scram—to leave quickly (from scramble) • screwy—crazy • sex appeal—physical attractiveness • spiffy—elegant, fashionable • swanky—ritzy • swell—marvelous • upchuck—to vomit • whoopee—boisterous fun, a loud party What are the modern youth equivalents? Source: This Fabulous Century: Sixty Years of American Life, Vol. III: 1920-1930 (New York: Time-Life books, 1969), 280-1. 16 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Rights and Dreams—Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness "From John Winthrop to Jefferson to Lincoln, Americans have been defined by our sense of our own exceptionalism—a sense of destiny that has, however, always been tempered by an appreciation of the tragic nature of life." —Jon Meacham, "Free to Be Happy," Time (July 8, 2013): 40 A belief in serendipity often pays off. As the author was finishing these materials, the early July issue of TIME magazine arrived, its "Pursuit of Happiness" issue, with Jay Gatsby used as the prime example for the principle that "experience teaches us that the more aggressively we pursue [personal happiness], the harder it can be to find." Journalist and historian Jon Meacham's essay, "Free to Be Happy," offers us perspective on what the right to that pursuit has meant to Americans, quoting our basic documents and their context in Enlightenment political thought: • First there was the Virginia Declaration of Rights, drafted by George Mason in 1776: 1. That all men are created equally free and independent, and have certain inherent natural rights, of which they cannot, by any Compact, deprive or divest their posterity; among which are the enjoyment of Life & Liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, & pursuing and obtaining Happiness & Safety. • Thomas Jefferson's subcommittee report to the Second Continental Congress in June of 1776 faced political critique and compromise, as the original text shows: Leonardo DiCaprio and Carey Mulligan in the 2013 film In lifetime happiness trends "people are happiest in their youth and golden years. Joy dips in middle age." • How old are the major characters in the novel? Why does Jay Gatsby want to go back to his youth and start again? What happens in the middle years of life that changes happiness? Does Nick's realization at the Plaza that it is his 30th birthday relate to this idea? Essays and quotations from July 8-15, 2013 double issue of Time We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal & independent; that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, & the pursuit of happiness…. [only one of the edits shown] Mason acknowledges an economic aspect associated with pursuing happiness; Jefferson gives us the pursuit. And what is that happiness they mention? • Aristotle, an anchor of political thought from the ancient world, says happiness is not personal; "it was an ultimate good, worth seeking for its own sake," in other words, "virtue, good conduct and generous citizenship," a social matter. On this point, the founding fathers, like other Enlightenment thinkers, agreed: "the 18th century meaning of happiness connoted civil responsibility," and "once the Declaration of Independence was adopted and signed in the summer of 1776, the pursuit of happiness—the pursuit of the good of the whole, because the good of the whole was crucial to the geniune wellbeing of the individual—became part of the fabric … of the young nation." • From within this dream of America emerged the American dream, a more individual sense of the right to happiness and the definition of what that happiness is. In that regard, Americans tend to be about more and next, not a this is good. Time's other title essay, Jeffrey Kluger's "The Happiness of Pursuit," examines that aspect of our lives: "American happiness would never be about savor-the-moment contentment. That way lay the reflective café culture of the Old World.… Our happiness would be bred, instead, of an almost adolescent restlessness, an itch to do the Next Big Thing." • Consumptive happiness, buying and owning, too often brings boredom rather than happiness, Kluger notes. We now have a happiness industry, with self-help programs and products bringing in as much income annually as do Hollywood films. Yet, he also mentions, in the 2012 World Happiness Report, the U.S. ranks only #23 of 50, with Iceland, New Zealand, and Denmark heading the list, and Singapore, Malaysia, and Vietnam ranking higher above the U.S. For us as a group, perhaps not for others, money fuels a sense of happiness, even if things do not. Gatsby and the American Dream • How does Jay Gatsby define his own American dream? How does Tom Buchanan define his? The novel is built on contrasts from the moment Nick comes from the West to the East and then drives from West Egg to East Egg. Does Fitzgerald set these two men and two definitions on a "collision course"? Or is Tom the usual boorish view and Gatsby the more rare individual who has a real dream? Or is it an illusion? a delusion? What's the difference and how would that affect our view of the story? What does Fitzgerald see and say about American collective happiness and Americans' consumptive happiness? 17 The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy Additional Activities HISTORY • Research the background of the Prohibition movement and how the 18th Amendment came to be passed, what the results of Prohibition were and how they changed the country, and how many areas of the U.S. are still "dry" today and why. What is the history of social/moral lifestyle legislation in the U.S. Compare laws limiting access to commodities such as alcohol to those allowing access to commodities such as firearms and ammunition, both of which are or have been hot political topics. • Consider how the experience of leading machine gun units in World War I compares to returning to the economic and social context of America for Gatsby. • Research the political, economic, and social developments in the U.S. from its involvement in World War I until the Wall Street Crash in 1929. What affects policies, attitudes, and lifestyles? What defines America during this time? How does America change? How like America in the 1920s are we today? Luxury on Long Island's Gold Coast—Oheka, the second largest private residence in the U.S., built in 1919 by banker Otto Herman Kahn. Its entry hall was used as the basis of Gatsby's entry hall in the 2013 film. THE ARTS • The 1920s were a time of great development and change in music and dance, the visual arts, and literature. Listen to the popular songs Fitzgerald mentions in the novel and decide how their lyrics and melodies are woven into the ideas of the novel, i.e. how apt they are: • “The Sheik of Araby” • “The Love Nest” • “Ain’t We Got Fun” • “Three O’Clock in the Morning” • “The Rosary” • “Beale Street Blues” How ironic is it that this Jazz Age novel does not use jazz? What was 1920s' music? • The cover of the first edition of the novel is justly famous. How does it visually express the essence of the novel? How does it reflect movements in contemporary art? What was going on in the visual arts in the 1920s? • Create your own design for the cover. • Research 20th-century film censorship codes and how Gatsby's action fares. LITERATURE • Initial dialogue—consider the relevance and import: --Tom Buchanan—after two pages of description of his ostentatious wealth, cruelly powerful physique, and restlessness, he says to Nick, "I've got a nice place here"— pride, ownership, and conscious understatement of his opulent domestic display. --Daisy Buchanan—after a description of the airborne curtains and figures in white on the sofa, Daisy says, "I'm p-paralyzed with happiness"—showing an inability to move and an avowal of joy, ironic given the facts of her marriage revealed shortly thereafter. --Nick Carraway—he narrates for pages before he enters the novel's dialogue with a response to Daisy's question about Chicago, "Do they miss me?" Nick replies, "The whole town is desolate. All the cars have the left rear wheel painted black as a mourning wreath, and there's a persistent wail all night along the north shore"— imaginative and a view of mourning and display. Note that Nick ends the novel as almost the lone mourner for Gatsby, who gets no sense of loss from the community. • If, according to the East Eggers, one is defined by where one lives, who are the Wilsons, who live near the trash dump? Are they trash to Tom Buchanan? • The novel establishes an image pattern about driving and automobiles, starting with Nick's comment to Jordan, "you're a rotten driver." How do the various drivers drive in the novel, and what else does that tell us about them? Is driving an indicator of life and values? of the story's action? • Debate the character and values of Tom Buchanan, Daisy, Jay Gatsby, and Nick Carraway. Are they sympathetic or not? Are they moral/good or immoral/ bad people? Are they responsible or irresponsible regarding the action? • Debate the value of performing the novel in another medium and how well it is or can be accomplished, using the recent Luhrmann film and the ASF production. The Great Gatsby adapted by Simon Levy 2013-2014 SchoolFest Sponsors Supported generously by the Roberts and Mildred Blount Foundation. PRESENTING SPONSOR State of Alabama SPONSORS Alabama Power Foundation Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama Hill Crest Foundation CO-SPONSORS Alagasco, an Energen Company Hugh Kaul Foundation Robert R. Meyer Foundation PARTNERS GKN Aerospace Honda Manufacturing of Alabama, LLC Mike and Gillian Goodrich Foundation Publix Super Markets Charities Photo: Alamy PATRONS Elmore County Community Foundation Target Photo: Haynes