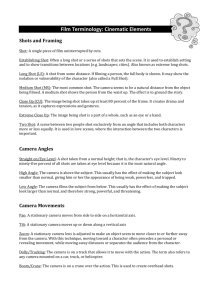

Film Language and Elements of Style

advertisement