Methodology of the Social Development Indices

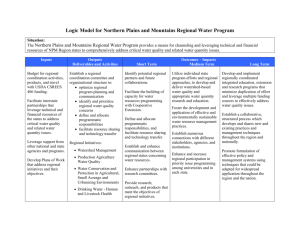

advertisement