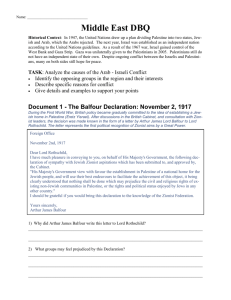

British foreign policy decision-making towards Palestine during the

advertisement