View/Open - East Bay

THE EFFECT OF EXTRA EFFORT ON THE ACQUISITION OF

OBSERVING RESPONSES IN DISCRIMINATION LEARNING

A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of

California State University, Hayward

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree

Master of Science in Human Resource Management

By

Stevan Charles Bennett

June 1993

Copyright@ 1993 by Stevan c. Bennett i i

ABSTRACT

The Effect of Extra Effort on the Acquisition of

Observing Responses in Discrimination Learning by

Stevan Charles Bennett

A study of discrimination learning using albino rats was undertaken. Theory holds that organisms prefer conditions where stimulus cues provide information predicting forthcoming reward or nonreward over conditions where this information is not provided. In 1952, Wyckoff performed an experiment with pigeons in which he attempted to isolate the behavior by which attention leads to discrimination learning. He called this attention behavior the observing response. He concluded from his results that information predicting reward or nonreward reinforces observing. In 1956, Prokasy performed a similar experiment using albino rats in an E-shaped maze. Results showed that the subjects preferred a condition allowing them to predict forthcoming reward or nonreward over a condition that did not.

Subsequent research indicated that this preference depended on a number of variables. Manipulating these variables led to results including preference for predictable condition, no preference for either condition, or preference for unpredictable condition. iii

The present study examined the effect of extra effort on preference for predictable conditions. Four groups of rats were run in an E-maze. One group replicated the Prokasy study. Two groups had extra lengths added to the predictable side. One group was used as a control to find if the extra length was discernible to the subjects.

Results of this experiment did not support the theory that information predicting reward or nonreward is reinforcing. Extra length added to the predictable side significantly reduced the preference for that side.

Rather, subjects appeared to choose the condition that provided the greatest chance of reward with the least amount of effort. iv

THE EFFECT OF EXTRA EFFORT ON THE ACQUISITION OF

OBSERVING RESPONSES IN DISCRIMINATION LEARNING

By stevan Charles Bennett

Approved: Date:

V''/".J r I v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Dr.Gene Steinhauer for his helpful comments, discussions and guidance on this project.

I would also like to thank Dr. John Lovell for getting the process started. Special thanks to Loran and Tom Vetter for their comments and help in preparing this document.

Above all, I wish to express my heartfilled gratitude to my wife, Lynne. Without her loving support I never would have been able to undertake this effort. vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Tables . .

List of Figures

Chapter

1.

2.

Introduction

Experimental Method and Results

Apparatus

Subjects

. • . • • . .

Procedure: Phase I

Trials

Results: Phase I

Procedure: Phase II . . . • • . . . •

Results: Phase II . . . . . . . • . . • •

3. Discussion • • .

Bibliography . • • . .

Page viii ix

1

18

18

20

21

34

39

23

23

29

29 vii

TABLES

Page

Table

1.

2.

3.

Anova 4 Groups by 16 Days . • • . • .

Scheffe F-Test Results . . . . . . . . . • .

Anova 2 Groups by 10 Days

25

27

31 viii

FIGURES

Figure

1.

2.

3.

E-Maze . . . . . .

Mean Choice Data Phase I

Mean Choice Data - Phase II

Page

. . . . . .

19

24

30 ix

Chapter 1

Introduction

In order for discrimination learning to occur subjects must attend to the discriminative stimuli. Since attention is hard to measure, Wyckoff developed an operational definition he termed the "observing response 11 .1

Wyckoff defined the observing response as 11 any response which results in exposure to the pair of discriminative stimuli involved".2 His general hypothesis was "exposure to the discriminative stimuli will have a reinforcing effect on an observing response to the extent that the subject has learned to respond differentially to the discriminative stimuli produced by the observing response 11 .3

To test this hypothesis, Wyckoff designed an experiment to show that:

1) Differential reinforcement led to an increase in the observing response.

2) Nondifferential reinforcement led to a decrease in the observing response.

3) Reversing a well-established discrimination will produce a temporary decrease and subsequent increase in the observing response.

4) If the probability of the observing response is low, discrimination formation will occur rapidly after a certain amount of time due to the increased exposure to the discriminative stimuli.4

1

2

Pigeons in modified Skinner boxes were pretrained to peck at a translucent key. The key was lighted white until the observing response occurred. The observing response consisted of stepping on a pedal built into the floor of the training box. Wyckoff stated:

The use of the pedal-pressing response enabled us to satisfy the following requirements:

1) The response was easily measured and recorded.

2) We can be reasonably certain that the bird was exposed to the discriminative stimuli if the observing response occurred, and that the bird was not exposed to the discriminative stimuli if the observing response failed to occur.

3) The observing response was relatively independent of the effective response of key-pecking. Pedal pressing was not a necessary complement of the effective response, nor was it in competition with the effective response.

4) The initial probability of an observing response could be adjusted, by the placing of the pedal, to obtain a value which would ensure learning within a reasonable time, but which could also increase.5

When the observing response occurred the key turned from white to either green or red. One color signified reward, the other color signified nonreward. Pecking rates on the key, and pedal presses, were recorded. After a preliminary training session subjects were given 75-minute sessions daily for five days. Trials consisted of 30second intervals. In the differential condition the observing response resulted in reinforcement at the end of the 30-second interval when the red light came on and the key was pecked. Nonreinforcement occurred when the

3 observing response was made and the green light came on.

Reward was not correlated with the color of the key in the nondifferential condition. In this condition reward occurred randomly on 50% of trials. If the subject did not make the observing response the translucent key remained white and reward occurred at random on half of the trials.

Subjects were divided into groups of discrimination, nondiscrimination, discrimination reversal, and discrimination extinction.

Results confirmed the specific and general hypotheses. Subjects in the discrimination group increased the rate of observing responses (pedal-pressing), while those in the nondifferential group decreased their rate of the observing response. Reversal of the discriminative stimuli resulted in a drop in observing responses followed by an increase to previous high levels. Also, as hypothesized, when the probability of the observing response was low discrimination occurred at a rapid rate after a period of time had passed.

It is important to realize that the frequency of reward did not change as a function of making the observing response. Subjects gained only information, in the differential condition, as to whether reward or nonreward was forthcoming. Reinforcement in all conditions occurred on 50% of the trials. Wyckoff theorized that the

"discriminative stimuli themselves take on a secondary

4 reinforcing value during the course of discrimination learning". 6 Wyckoff adds that "conditioned reinforcing value attained by the positive stimulus served to strengthen or maintain the observing response during differential reinforcement". 7

To test Wyckoff's theory in another context,

Prokasy developed a procedure involving an E-shaped maze using rats as subjects. 8 Prokasy wanted to see if the reinforcing effect of exposure to discriminative stimuli would occur with rats. The specific hypothesis was to see whether rats would "show a preference for conditions enabling them to anticipate the presence or absence of food over conditions not enabling them to anticipate the presence or absence of food, when the average amount of food resulting from a choice of either condition was the same".9 Prokasy states that his term "anticipates is analogous to Wyckoff's 'observing response'".lO

The E-maze consists of three major parts. The center arm of the E includes a start box and short runway leading to a choice point. A long runway (the backbone of the E) extends in both directions from the choice point to the outside arms of the E. Each outside arm contains a delay chamber and a goal box. Subjects cannot see into the outside arms from the choice point. Guillotine doors are placed at the end of the start box leading to the choice point, the long runway on either side of the choice point

5 to prevent backtracking once a choice is made, the entrance of the delay chamber to prevent backtracking once the subject has entered the chamber, and the entrance of the goal box. The walls and floor of the delay chamber and goal box were painted either black or white. Black or white outside arm sections were interchangeable. In the differential condition one color was correlated with reward, the other color with nonreward. In the nondifferential condition color was not correlated with reward or nonreward. Hardware cloth was attached to the floor of the maze on one side, from the choice point to the goal box, to help subjects discriminate the left side from the right. A trial consisted of the subject being placed in the start box and the door raised. Once the subject made a choice the choice point door closed behind it. When the subject entered the delay chamber a door again closed behind it. After the specified delay time the door to the goal box was raised and the subject encountered either reward or nonreward. Conditions were counterbalanced so that both black and white signified reward and nonreward, and so that outside arms were both discriminative and nondiscriminative. The procedure was designed so that subjects experienced equal time in the differential and nondifferential conditions. This was accomplished by giving subjects both free trials (subject chooses which outside arm to enter), and forced trials (subject is forced

6 to one outside arm or the other by closing a choice point gate). Subjects were given time prior to the experiment to explore the maze. Subjects ran four trials per day for two days, then ran eight trials per day for the remainder of the experiment. Delay time in the delay chamber was 30 seconds. Reward consisted of .25 grams of the subjects regular food.

Results of this study showed that on free choice trials subjects significantly preferred the consistent

(differential) side. Prokasy stated that the most likely account for these results was Perkins preparatory response theory. Perkins argued that the organism learned to prepare itself (by means of salivating or not salivating) in the presence of the discriminative stimuli. If the discriminative stimulus signaled reward, more salivating would occur. If the discriminative stimulus signaled nonreward, less salivating would occur.1 1 Prokasy said that this preparatory response alone could not account for the preference for the consistent side. He argued that in order for preference for the consistent side to occur the appropriate preparatory responses must be "maximally reinforcing" in preparation for reward or nonreward.

Maximal reinforcement occurs when the amount of salivating is greater with reward and minimal with nonreward. This condition occurs on the consistent side, but does not occur on the inconsistent side.12 "As a result, a choice to the

7 consistent side always immediately precedes a relatively more reinforcing condition, and thus this response tendency is increased more than the tendency to make the opposite turn".l 3

Before continuing this discussion it is necessary to point out that while Prokasy claimed his study tested

Wyckoff's theory in another context, his procedure differed from Wyckoff's in one important respect. Wyckoff's subjects were placed in either the differential condition or the nondifferential condition to see what affect these conditions would have on attending behavior. Also, these subjects could choose not to make the observing response and still receive reward on 50% of their trials. Prokasy's subjects were not given this option. These subjects had to choose between the differential condition or the nondifferential condition. Subjects in Prokasy's study that did not make a choice were given additional training until they learned to do so.

Subsequent studies began to show that the emergence of the observing responses was subject to certain conditions. If these conditions were not present the observing response did not occur. Wehling and Prokasy found that drive level, or motivation, affected the observing response. 1 4 In this study rats were placed in one of two conditions. One condition was a 20-hour food deprivation schedule (high drive), while the other

8 condition was a 12-hour food deprivation schedule (low drive). All other conditions replicated the original

Prokasy study. The high drive group performed similar to those in the Prokasy study, preferring the predictable side by a significant margin. The low drive group did not significantly respond to the discriminative stimuli. These results prompted the authors to conclude that "there is no evidence that the low drive group acquired the observing response 11

•

15

Lutz and Perkins, using rats in an E-maze, varied the amount of delay prior to entry into the goal box.l6

They used delays of o, 3, 9, 27, and 81 seconds. All other conditions conformed to Prokasy's study. Results showed that delays of 3, 9, 27, and 81 seconds resulted in significant preference for the predictable choice side.

However, the o-second delay group showed a distinct preference for the unpredictable choice side. The authors note that the difference between the o-second delay and all other groups was statistically significant. The conclusion for this preference for the unpredictable side was that the

0-second delay provided such a brief observing responsereward interval that it did not provide differential reinforcement.1 7 The authors did not explain how this would account for a preference for the unpredictable side.

Perkins preparatory response theory and Prokasy's maximally reinforcing preparatory response theory do not address a

9 possible preference for the unpredictable side. This creates a problem for their theories. In reference to

Perkins preparatory response theory, Daly points out that, while the theory accounts for much of the data, i t cannot answer the question "when would salivating the correct amount be less reinforcing than not knowing how much to salivate?".18 This argument holds true for Prokasy's maximally reinforcing preparatory response theory as well.

Mitchell, Perkins and Perkins took a different approach by varying the magnitude of reward. Again using rats in an E-maze, they separated groups into reward sizes of 1-unit, 5-units, and 25-units. A unit of food coexisted of .045 grams. Results showed that the 5-unit and the 25unit reward groups preferred the predictable choice side.

The 1-unit group performed at the chance level.19

Kelleher, using chimpanzees, found that "variables determining the frequency of stimulus-producing responses and their relationship to discrimination performance" to be relevant to observing response acquisition.2° Kelleher argued that "the Wyckoff technique had the disadvantage that the pedal-pressing response had a very high operant level, and frequently the Rs (stimulus-producing response) rates were high despite poor discriminations. 112 1 This may have been due to the fixed interval (FI) schedule of reinforcement. Kelleher states that "under an FI schedule, the passage of time during Rs responding increases the

10 probability that Rf (food-producing response) will be reinforced. Thus, an Rf following a series of Rs's is likely to be reinforced and a chain of responding develops.n22 By altering the procedure to prevent such a chain, Kelleher found that the rate of Rs fell substantially. The procedural change consisted of a 3second delay if the observing response occurred immediately prior to, or simultaneously with the end of the fixed interval session.23

Atkinson, in a study using human subjects, found a relationship between reinforcement schedules and the observing response. Two types of trials, each involving two different observing responses, were presented. It was found that preference for one of two observing responses depended on the amount of difference between varying reinforcement schedules of the two trial types.24

The fact that there are variables that can determine whether an organism makes the "observing response" calls for a further study of Wyckoff's hypothesis. Both the Wyckoff and Prokasy procedures incorporated variables later shown to affect observing response acquisition. In both studies subjects were reduced to 80% of ad lib body weight prior to onset of the trials. This constitutes a high drive level (hunger). In the Wyckoff procedure reinforcement did not occur from 0 to

30-seconds after the key was pecked. The Prokasy procedure

11 used a 30-second delay. Reward for the subjects of the

Wyckoff study was 4 seconds of access to food. No conclusions can be made as to whether this constitutes a small or a large reward. In the Prokasy study subjects were given slightly more than the 5-unit reward used in the

Mitchell, Perkins and Perkins study.

The veracity of Wyckoff's procedure has also been questioned. Hirota replicated Wyckoff's procedure and found that the placement of the foot pedal determined the amount of time that subjects spent pedal-pressing.25

Hirota states that "the present expe~iments suggest that the correlation between key-response rates and pedalstanding time occurs as a result of the physical relationship between the key and the pedal."26 Hirota also declares that "Wyckoff's assumption that key responses and pedal-standing time are relatively independent of each other is not supported by the present results."27

In light of the additional information contained in the studies cited above, the definition of an observing response set forth by Wyckoff appears inadequate unless it addresses the impact of variables upon which observing response acquisition is dependent. It is not clear how salient the observing response is in discrimination learning when examined separately from these intervening variables. In addition, Wyckoff's theoretical assertion that "discriminative stimuli themselves take on a secondary

12 reinforcing quality during the course of discrimination learningn28 can be questioned in light of the studies cited above. In the E-maze procedure subjects receive equal exposure to both discriminative and nondiscriminative stimuli. These subjects, under the conditions cited above, do not always respond differentially to the discriminative stimuli.

Another question that arises when examining the observing response is whether there are other factors which could influence its acquisition. The present study was undertaken to examine one such factor, extra effort, or the amount of energy needed to attain the information concerning reinforcement the discriminative stimuli contain relative to the amount of energy needed to attain reinforcement without this information. The rationale for this study was a result of two questions arising from an examination of the literature pertaining to discrimination learning. First, the procedural differences noted above between the Wyckoff study and the Prokasy study raise the issue of the original intent of Wyckoff's study. Wyckoff held that the observing response consisted of some additional behavior that changed the subjects situation from unpredictable to predictable. He introduced pedalpressing as an observing response to introduce this additional behavior. Prokasy, while demonstrating the preference for predictable situations over unpredictable

13 situations in the E-maze study, did not introduce any additional behavior necessary to access the discriminative stimuli into his procedure. Subjects turned one way towards the predictable side, or the other way towards the unpredictable side. The amount of effort needed to reach the goal box is the same in both directions. As such,

Prokasy appears to have missed the fundamental point of

Wyckoff's additional effort requirement. The present study, by adding extra effort to reach the discriminative side as the additional behavior to access the discriminative stimuli, utilizes the Prokasy procedure in a manner more consistent with the stated intent of the

Wyckoff procedure.

Second, research by DeCamp29 and Yoshioka30 has shown that rats, given the choice of two lengths of paths leading to reinforcement, prefer the shorter path. This knowledge gives us a method by which the relative value of the information gained by exposure to the discriminative stimuli can be measured, especially when other variables known to promote the preference for predictable outcome are factored in. If the discriminative information has value, subjects should be willing to go to greater lengths to attain this information. If the discriminative information is of little value, subjects should tend to choose the path to reinforcement that offers the greatest probability of reward with the least amount of effort. The present study

14 was undertaken to test the hypothesis that the frequency of observing responses will be lower under conditions where greater effort is needed to reach the discriminative stimuli. More specifically, the hypotheses are:

1) Rats placed under conditions where greater effort is needed to achieve differential reinforcement than is needed to achieve nondifferential reinforcement will not acquire the observing response. This will be Phase I.

2) When the condition of extra effort to attain the discriminative stimuli is introduced to rats who have acquired the observing response, under conditions of equal effort, the frequency of observing responses will decline.

Conversely, when the condition of extra effort to obtain the discriminative stimuli is removed, the frequency of observing responses will increase. This will be Phase II.

For the purpose of this study, the differential condition will be referred to as the predictable side. The nondifferential condition will be referred to as the unpredictable side.

15

NOTES

1. L. Benjamin Wyckoff, Jr. "The Role of

Observing Responses in Discrimination Learning: Part I."

Psychological Review 59 (1952): 431-442.

2. Wyckoff, Part I, 431.

3. Wyckoff, Part I, 431.

4. L. Benjamin Wyckoff, Jr. "The Role of

Observing Responses in Discrimination Learning: Part II."

In D. P Hendry (Ed.), Conditioned Reinforcement, 1969

(Homewood, Illinois: The Dorsey Press) 237-260.

5. Wyckoff, Part II, 239.

6. Wyckoff, Part I, 434.

7. Wyckoff, Part II, 251.

8. William F.Prokasy. "The Acquisition of

Observing Responses in the Absence of Differential External

Reinforcement." Journal of Comparative and Physiological

Psychology 49 (1956): 131-134.

9. Prokasy, 131.

10. Prokasy, 131.

11. Charles c.

Perkins, Jr. "The Stimulus

Conditions Which Follow Learned Responses." Psychological

Review 62, no. 5 (1955): 341-348.

12. Prokasy, 134.

13. Prokasy, 134.

16

14. Hildegard E. Wehling, and William F. Prokasy,

"Role of Food Deprivation in the Acquisition of the

Observing Response." Psychological Reports 10 {1962): 399-

407.

15. Wehling and Prokasy, 404.

16. Robert E. Lutz, and Charles c. Perkins, Jr.

"A Time Variable in the Acquisition of Observing Response."

Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 53, no.

2 {1960): 180-182.

17. Lutz and Perkins, 181.

18. Helen B. Daly. "Preference for Predictability is Reversed When Unpredictable Nonreward is Aversive:

Procedures, Data, and Theories of Appetitive Observing

Response Acquisition. In I. Gormezano and E. A. Wasserman

(Eds.), Learning and Memory: The Behavioral and Biological

Substrates. 1992 ( Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence

Earlbaum Associates) Ch.5, 92.

19. Kevin B. Mitchell, Nancy P. Perkins, and

Charles c.

Perkins, Jr. "Conditions Affecting Acquisition of Observing Responses." Journal of Comparative and

Physiological Psychology 60 {1965): 435-437.

20. Roger T. Kelleher. "Stimulus-Producing

Responses in Chimpanzees." Journal of Experimental

Analysis of Behavior 1, no. 1 {1958): 88.

21. Kelleher, 87.

22. Kelleher, 100.

17

23. Kelleher, 89.

24. Richard c. Atkinson. "The Observing Response in Discrimination" Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62

(1961): 253-262.

25. Theodore T. Hirota. "The Wyckoff Observing

Response-A Reappraisal." Journal of the Experimental

Analysis of Behavior 18 {1972): 263-276.

26. Hirota, 275.

27. Hirota, 275.

28. Wyckoff, Part I, 431.

29. J. E. De Camp. "Relative Distance as a Factor in the White Rat's Selection of a Path." Psychobiology 2, no. 3 {1920): 245-253.

30. Joseph G. Yoshioka. "A Preliminary Study in

Discrimination of Maze Patterns by the Rat." University of

California Publications in Psychology 4, no. 1 (1928): 1-

18.

Chapter 2

Experimental Method and Results

Apparatus

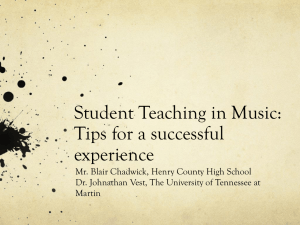

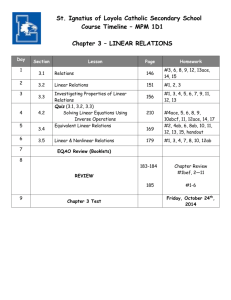

The E-maze, seen in Figure 1 below, was based on the one used in Wehling and Prokasy, and differed only slightly in actual dimensions.31 The floor was 4 inches wide between walls. The walls were 4 inches high. The start box and runway leading to the choice point consisted of one unit. The start box was 10 inches long, and the runway leading to the choice point was 11 inches long. The goal boxes were 10 inches long. The delay chambers and all extra length sections were 11.5 inches long. The delay chamber and goal box together comprised one movable unit.

The runway from choice point to the turn leading to the outside arm was 21 inches. The entire inside of the maze was painted flat gray. Flat gray anti-skid material covered the floor of all sections to the right of the choice point. Removable pieces of this material were used when extra length was added to the right side. The top of the maze was covered with clear plexiglass that was hinged to facilitate subject handling and maze cleaning.

Guillotine doors were made from gray sign-making material nearly identical to the shade of the rest of the maze.

18

D c

B

D

E E

F

A

F

A Start box

B Choice Point Runway c -

Choice Point

D -

Long Runway

E Delay Chamber

F Goal box

G Extra Length Sections

1-----1 Guillotine Door

Figure 1

E-Maze

G

G

G

G

I

G

I G

....

10

20

The colors in the delay chambers and goal boxes were manipulated with black and white plexiglass inserts.

The maze was situated in a fairly quiet room. It was placed on a counter 36 inches off the floor. On the backbone and two outside arms of the E, neutral colored walls were placed around the maze, 6 inches away from the maze walls. The experimenter sat behind the start box, providing as little impact as possible during trials. The room was lit by four 48 inch fluorescent bulbs, mounted in the ceiling behind opaque covers.

Subjects

Thirty-two male, Sprague-Oawley derived, Simonsen

Albino rats were used for this study. All were experimentally naive. The subjects were 81 days old at the start of the experiment. Two days prior to the start of the trials, subjects were placed on a 23-hour food deprivation schedule. They were allowed 45 minutes of free feeding per day. During the first two days of the experiment it was noted that the subjects were losing more weight then was necessary. As a result the feeding was changed to subjects receiving approximately 25 grams of food at the completion of all the days trials rather than a fixed time of free feeding. This feeding change stabilized the subjects weight without any apparent reduction the drive level. Food consisted of Simonsen laboratory rat chow.

21

Procedure: Phase I

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of four groups, with eight subjects per group.

Group 1) E-maze: This group was used to replicate the original Prokasy study. 32 Both outside arms of the maze were of equal length.

Group 2) E-maze plus 23-inches: This group had two

11.5-inch sections added to the predictable choice side after the turn into the outside arm, before the delay chamber.

Group 3) E-maze plus 46-inches: This group had four 11.5-inch sections added to the predictable choice side after the turn into the outside arm, before the delay chamber.

Group 4) Control: This group was used to discern whether extra length affected choice behavior. For this group the color inserts in the delay chambers and goal boxes were not used. Reinforcement was on a predetermined, randomly assigned 50% schedule. This group was broken down into two subgroups:

A) 4 subjects had 23-inches of extra length added to one outside arm of the maze, with 2 subjects assigned to the long left arm condition and 2 subjects assigned to the long right arm condition.

B) 4 subjects had 46-inches of extra length added to one outside arm of the maze, with 2 subjects assigned to

22 the long left arm condition and 2 subjects assigned to the long right arm condition.

All conditions were counterbalanced. Four subjects in each of groups 1, 2, and 3 had the predictable side on the left outside arm of the maze. Four subjects in each of the groups 1, 2, and 3 had the predictable side on the right outside arm of the maze. Black was the predictor of reward for half of the subjects in each of groups 1, 2, and

3. White was the predictor of reward for the other half of the subjects in each of groups 1, 2, and 3.

Two days prior to the start of the experiment each subject was given 15 minutes of exploration time in the maze. Food cups, including food, were placed in both goal boxes during exploration time. All but two of the subjects actively explored the entire maze. These two subjects were given an additional 15 minutes exploration time, during which they also actively explored all parts of the maze.

Reward during the experiment consisted of .045 gram

Noyes pellets, 12 pellets per reinforced trial, for a total of .54 grams per trial. Delay time prior to entry into the goal box was 10 seconds. A stopwatch was used to time the delay period. Subjects were removed from the goal box when the re .

ward was eaten. On nonrewarded trials subjects remained in the goal box for 5 seconds.

23

Trials

Subjects ran eight trials per day, six days a week for a total of 16 days. A trial consisted of the subject being placed in the start box. When the subject faced the start door the door was raised. The subject approached the choice point and turned right or left. Once the subject had moved beyond the choice point the door on that side was closed behind it to prevent backtracking. When the subject entered the delay chamber a door was again closed behind it to prevent backtracking. After the 10 second delay the door to the goal box was raised, exposing the subject to the reward or nonreward condition.

The first 4 trials for each subject were free choice trials. The last four trials were forced trials to the opposite side of the respective free trials. For example, if the subject chose left on free trial 1, right on free trial 2, left on free trial 3, and right on free trial 4, it was then forced right on trial 5, forced left on trial 6, forced right on trial 7, and forced left on trial 8. Each subject was rewarded 50% of the time, balanced across conditions. Thus, on both the predictable and the unpredictable side, each subject had 2 rewarded and

2 unrewarded trials daily.

Results; Phase I

Figure 2 shows the mean percent choice data for the four groups, for each day of Phase I of the experiment.

Percent

Choices

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

1

Day

2 3 4 5 6

~

7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

---Group 1

-[}-Group 2

---Group 3

--oGroup 4

Figure 2

Mean Choice Data - Phase I t-J

~

25

50% is the point at which choices are at the chance level.

Percentages above 50% represent preference for the predictable side. Percentages below 50% represent preference for the unpredictable side. On day 9, Group 1 began to show a consistent preference for the predictable side. Groups 2 and 3 also began to show consistent preference for the unpredictable side from day 9 on. Group

4 began to choose the shorter path consistently from day

10.

A 2-factor, groups by days, repeated measures of analysis of variance indicated that there was no significant difference between the 23-inch and the 46-inch conditions in Group 4, (f=1.968, df 1,6, p>.20). As a result, these conditions were collapsed, producing one group of 8 subjects. This resulted in four groups of equal size for further analysis.

Source

Groups

Subjects within Groups

Days

Groups x Days

Days x Subjects within Groups

TABLE 1

ANOVA - 4 GROUPS BY 16 DAYS

DF

3

28

15

45

420

Sua of Squares Mean Square F Value

21.428 137192.383

59755.859

13706.055

65971.68

204306.641

45730.794

2134.138

913.737

1466.037

486.444

1.878

3.014

Pr > F l.OE-4

0.0236 l.OE-4

26

Next, a 4-groups by 16-days, repeated measures of analysis of variance was conducted on the choice data. As seen in Table 1, the groups by days interaction was significant. This interaction suggests that group means differ on some days, but not on others. In order to understand the interaction, group means were compared by

Sheffe F-tests on each day. The results of these analyses are shown in Table 2. The pattern of significant Scheffe

F-tests confirm the choice trends shown in Figure 2.

Group 1 results conformed to those of the Prokasy study.33 These subjects preferred the predictable condition, with a mean preference level of over 90% by the end of the experiment. With the exception of subject 303, preference by this group was no less than 75% of free choice trials from day 10 through the end of Phase I.

Subject 303 was inconsistent in choosing preference until day 14, when the predictable side was chosen 100% of the time through day 16.

The subjects in Group 1, once a preference emerged, behaved in a consistent manner. They ran rapidly, and without hesitation, from the start box to the delay chamber. The exception was subject 303. This subjects behavior alternated between that of the rest of Group 1 and behavior representative of Groups 2 and 3. The behavior of

Groups 2 and 3 consisted of slowly approaching the choice point and stopping. After looking from side to side, one

TABLE 2

SCHEFFE F-TEST RESULTS

Day

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

1 - 2

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

*

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Groups - Phase I

1 - 3 1 - 4

-

-

-

-

2 - 3

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

9

* *

10 * *

11 * *

12 I * I *

13 I * I *

14 I * I *

15 I * I *

16 L * I *

* = significance at 95%

I

I

I

I

I

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

-

2 - 4

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

3 - 4

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Groups Phase II

1 - 3 Day

17 *

-

-

-

* 18

19

20

21

22 *

*

*

*

*

23

24

25

26

N

-..J

28 to several times, the subject would slowly proceed in the direction of choice. Often the subject would attempt to backtrack. This was prevented by the choice point gates.

Subject 303 hesitated at the choice point even when preference for the predictable side was 100%.

The results of Groups 2 and 3 confirmed the hypothesis that increased effort to attain discrimination stimuli reduces observing response acquisition. The behavior of these groups, as noted above, differed markedly from that of Group 1. These subjects rarely ran from start box to delay chamber. Rather, the behavior was one of caution or indecision. Movement was slow throughout the trial. The exception was when these subjects turned the corner to the delay chamber. At this point the subjects would sometimes run frantically back and forth between the choice point gate and the entrance to the delay chamber. on other occasions they would proceed slowly into the delay chamber. Once in the delay chamber the frantic behavior would begin.

Group 4 results indicate a trend towards the shorter of the two paths. One explanation of the lack of clear-cut results for this group may be the length of the runway. The research by DeCamp34 and Yoshioka35 used runways of six feet or more to achieve their results.

29

Procedure: Phase II

To provide further evidence that extra effort will affect observing response acquisition, conditions for Group

1 and Group 3 were reversed. Group 1 had a 46-inch section added to the outside runway on the predictable side. Group

3 had the 46-inch extra section removed from the outside runway on the predictable side. As in Phase I, all conditions were counterbalanced across conditions. Other than the removal or addition of the 46-inch section, all conditions were identical with those of Phase I. Phase II of the experiment ran for 10 days of trials.

If, as hypothesized, extra effort needed to obtain discriminative stimuli will reduce observing response acquisition, subjects in Group 1 should begin to reverse their preference for the predictable condition once the additional 46-inch section is added to the predictable side. Conversely, subjects in Group 3 should begin to show increased preference for the predictable condition once the extra length on this side is removed.

Results; Phase II

Figure 3 shows the mean percent choice data for the two groups, for each day of Phase II of the experiment. As in Phase I, 50% is the point at which choice is at the chance level, above 50% indicates preference for the predictable side, and below 50% indicates preference for the unpredictable side.

30

Percent

Choices

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

17

Day

18 19 20 21

---- Group 1

--..Group 3

22 23 24 25 26

Figure 3

Mean Choice Data - Phase II

A 2-factor, groups by days, repeated measures analysis of variance was conducted on the choice data for

Phase II. As seen in Table 3 below, the groups by days interaction was significant. Group means for each day of

Phase II were compared by Scheffe F-tests to better understand this interaction. The results of these analyses are shown in Table 2, on page 25. The pattern of significant Scheffe F-tests confirmed the choice trends seen in Figure 3.

31

TABLE 3

ANOVA - 2 GROUPS BY 10 DAYS

Source

Groups

SUbjects within Groups

Days

Groups x Days

Days x Subjects within Groups

DF

1

14

9

9

126

SUI of Squares Mean Square F Value

3753.906

16648.438

957.031

56519.531

42335.938

3753.906

1189.174

106.337

6279.948

336

3.157

.316

18.69

Pr > F

0.0973

0.9683 l.OE-4

Group 1 began to show an immediate decrease in preference for the predictable side. When first exposed to the new condition, the subjects stopped after turning the corner of the outside arm of the runway. After a few seconds, the subjects proceeded slowly down the runway to the delay chamber. In subsequent trials these subjects began to hesitate at the choice point. Running to the delay chamber decreased, and was replaced by slow, tentative movements with frequent stops. The exception to this behavior was subject 306. This subject continued to run from start box to the delay chamber until day 22.

After day 22, subject 306 also began to hesitate at the choice point. However, once a choice was made, the subject ran to the delay chamber.

Group 3 began to reverse preference for the unpredictable side from the first day of Phase II. These subjects also stopped when confronted with the new

condition on the predictable side for the first time.

Despite a continual increase in preference for the predictable side, these subjects continued to hesitate at the choice point and move slowly to the delay chamber.

32

NOTES

31. Wehling and Prokasy, 400.

32. Prokasy, 131-134.

33. Prokasy, 131-134.

34. De Camp, 245-253.

35. Yoshioka, 1-18.

33

Chapter 3

DISCUSSION

The results of this study support the hypothesis that frequency of observing responses will be lower when extra effort is necessary to obtain the discriminative stimuli. The frequency of observing responses for Groups 2 and 3 was low enough to be called a preference for the unpredictable side. Whether this proved to be the case, or that the subjects were exhibiting preference for the shorter route as earlier research by DeCamp36 and

Yoshioka37 has shown, these results do not support

Wyckoff's general hypothesis that "exposure to the discriminative stimuli will have a reinforcing effect on an observing response to the extent that the subject has learned to respond differentially to the discriminative stimuli produced by the observing responsen.38 Groups 2 and 3 did not respond to the discriminative stimuli during

Phase I. Due to the equal experience in both conditions, through free and forced trials, it can be reasonably assumed that these subjects were adequately exposed to the discriminative stimuli. This assumption is reinforced by the results of Group 1 during Phase I, and Group 3 during

Phase II of the experiment.

34

35

Group 1, under conditions of equal length to the predictable and unpredictable sides, responded to the discriminative stimuli by a significant margin in Phase I.

These subjects reversed their preference for the predictable side when extra length was added to this side.

The subjects in Group 3 began to start choosing the predictable side on free choice trials once the extra length was removed. The speed at which reversal occurred indicates that these subjects had learned the meaning of the discriminative stimuli on the predictable side, but chose not to use this information until the extra length was removed from this side.

These results suggest that more than the discriminative stimuli need to be taken into account when trying to understand the role of observing responses in discrimination learning. Wehling and Prokasy state that observing responses are not "a result of specific situational factors". 39 While the observing response may not be a result of specific situational factors, whether an organism responds to the discriminative stimuli is highly sensitive to specific situational factors. The literature is replete with studies showing increases in observing response behavior and preference for the predictable side when drive level is high, reward is sufficient, and reward is delayed. There is also research that shows that the observing response will be at chance level or lower if

36 these variables are not at optimal levels. Drive level, magnitude of reward, and delaying reinforcement, among other variables, all influence whether the discriminative information gained by making the observing response will be utilized. The present study adds effort to this list of variables.

One explanation for the effect of situational factors on the observing response is that the subject does not exhibit a preference for one condition or the other until it has experience with the environment it finds itself in. Repeated exposure to the numerous variables cause the subject to begin sorting out the relative values of each piece of information. Once this is accomplished, an expression of preference emerges. In some situations the various factors produce a situation where no clear preference is shown. In this case the subject vacillates between the two conditions.

In the present study, clear preferences were expressed for one side or the other. The only difference in conditions was the addition of extra length leading to the discriminative stimuli. In order to minimize the effects of reward magnitude, delay prior to goalbox entry and drive level (hunger), these variables were set at levels known to facilitate observing response acquisition.

This provides a measure of the strength of the information provided by the discriminative stimuli. The results show

37 that this information is not valuable enough to persuade the subjects to travel the extra length to reach it. They choose instead the side where reinforcement occurs 50% of the time regardless of the stimulus presented.

Wyckoff theorized that in order for discrimination learning to occur subjects must attend to the discriminative stimuli.40 He attempted to show that subjects can learn a new behavior in order to gain information, and that this information reinforces the tendency to make the observing response. The present study, using extra effort as the new behavior, does not support his results. As both the predictable and unpredictable sides in the present study utilized the same reward size, a study in which increasing reward on the extra length predictable side produces sufficient incentive for this side to be chosen may provide a further test

Wyckoff's theory.

NOTES

36. De Camp, 245-253.

37. Yoshioka, 1-18.

38. Wyckoff, Part I, 431.

39. Wehling and Prokasy, 399.

40. Wyckoff, Part I, 431-442.

38

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Atkinson, Richard c. "The Observing Response in

Discrimination Learning." Journal of Experimental

Psychology 62 (1962): 253-262.

Daly, Helen B. "Preference for Unpredictability is

Reversed When Unpredictable Nonreward is Aversive:

Review of Procedures, Data, and Theories of Appetitive

Observing Response Acquisition." In Learning and

Memory: The Behavioral and Biological Substrates. Eds.

I. Gormezano and E. A. Wasserman, 81-103. Hillsdale,

New Jersey: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, 1992.

De Camp, J. E. "Relative Distance as a Factor in the White

Rat's Selection of a Path." Psychobiology 2, no. 3

(1920); 245-253.

Hirota, Theodore T. "The Wyckoff Observing Response-A

Reappraisal." Journal of the Experimental Analysis of

Behavior 18 (1972): 263-276.

Kelleher, Roger T. "Stimulus-Producing Responses in

Chimpanzees." Journal of the Experimental Analysis of

Behavior 1, no. 1 (1958): 87-102.

Lutz, Robert E., and Charles c. Perkins, Jr. "A Time

Variable in the Acquisition of Observing Responses."

Journal of comparative and Physiological Psychology 53, no. 2 (1960): 180-182.

Mitchell, Kevin M., Nancy P. Perkins, and Charles c.

Perkins, Jr. "Conditions Affecting Acquisition of

Observing Responses in the Absence of Differential

Reward." Journal of comparative and Physiological

Psychology 60 (1965): 435-437.

Prokasy, William F. "The Acquisition of Observing

Responses in the Absence of Differential External

Reinforcement." Journal of Comparative and

Physiological Psychology 49 (1956): 131-134.

Wehling, Hildegard E., and William F. Prokasy. "Role of

Food Deprivation in the Acquisition of the Observing

Response." Psychological Reports 10 (1962): 399-407.

39

40

Wyckoff, L. Benjamin, Jr. "The Role of Observing Responses in Discrimination Learning: Part I." Psychological

Review 59 (1952): 431-442.

"The Role of Observing Responses in Discrimination

Learning: Part II." In Conditioned Reinforcement. Ed.

D.P. Hendry, 237-260. Homewood, Illinois: The Dorsey

Press, 1969.

Yoshioka, Joseph G. "A Preliminary Study in Discrimination of Maze Patterns by the Rat." University of California

Publications in Psychology 4, no. 1 (1928): 1-18.