Commercial Infrastructure in Africa

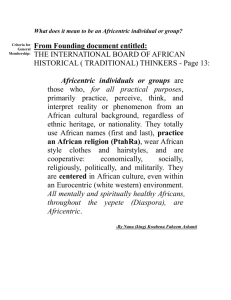

advertisement