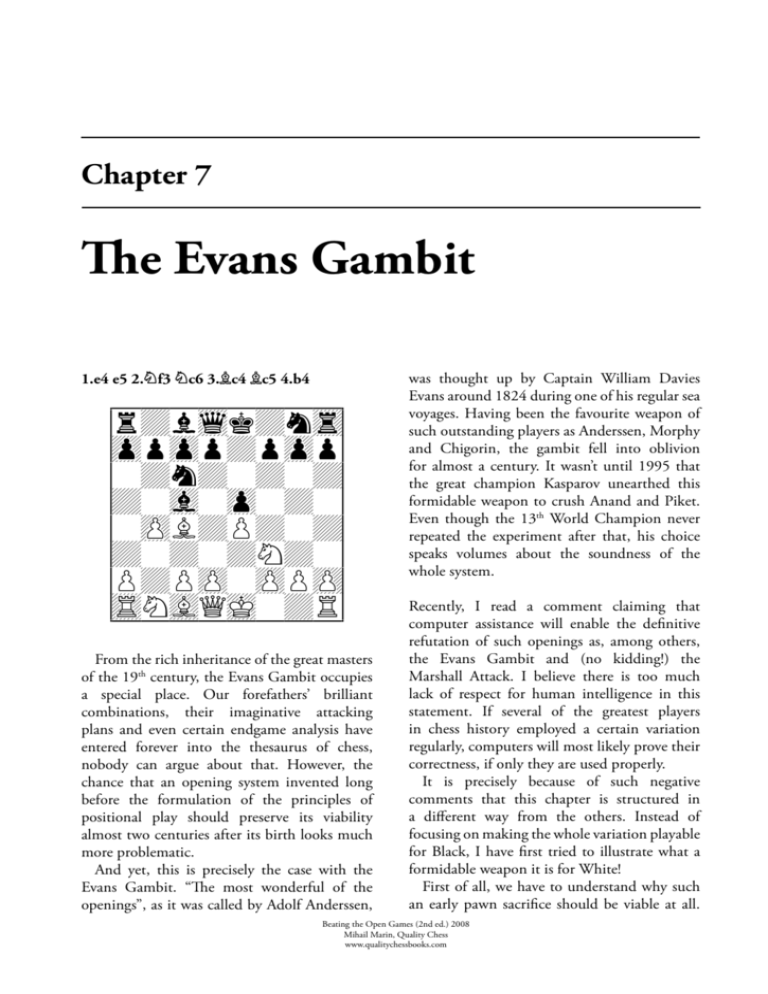

The Evans Gambit

advertisement