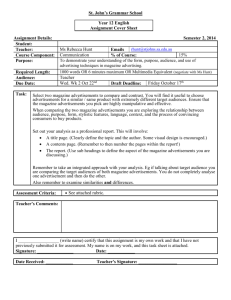

An Investigation into the Persuasiveness of Puffery in

advertisement