VLJs and Air Taxis

advertisement

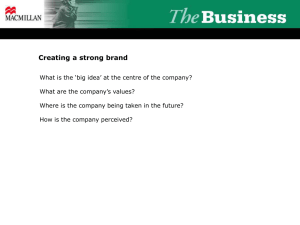

Commentar y VLJs and Air Taxis Balancing the Opportunities and the Challenges By Gerald W. Bernstein, Founding Partner, The Velocity Group The May/June 2006 issue of Managing The Skies provided two contrary perspectives on Very Light Jet (VLJ) and Air Taxi prospects in articles written by Bill Strait (“What are Very Light Jets and Are They Safe?) and Vaughn Cordle (“Dot-Coms with Wings: A Fun and Exciting Opportunity to Lose Money”). he two authors took extremely different positions. Vaughn Cordle is a well-reasoned industry veteran and his comments invariably reflect informed points of view. That being said, there are some points that he addressed somewhat weakly or did not address at all that really should be considered in developing a realistic outlook for VLJs and air taxis. Conversely, Bill Strait summarized very well many of the efforts undertaken in anticipation of large numbers of VLJ’s entering the general aviation and Part 135 fleets. However, he is perhaps a bit reliant on others’ opinions on some of the key issues rather than his own analysis. In this chasm between Bill’s unalloyed enthusiasm and Vaughn’s litany of potential pitfalls lies much room for a more balanced, research-based consideration of both the opportunities and the challenges provided by this new category of aircraft. You be the judge. T VLJ and Air Taxi Are NOT Synonymous Perhaps the only point of agreement between the two articles was that a Very Light Jet (VLJ) is a small jet of 10,000 pound or less maximum takeoff weight. Managing the Skies conveniently summarized the twelve major programs in an accompanying table. First, one can consider how VLJ’s are likely to sell in the existing market of turbine-powered aircraft. Both authors cited other sources on this point – I will fill in some details. This www.faama.org Table 1: Turbine Aircraft Purchases by Price, 2003 – 2004, Worldwide PRICES < $500 <$1000 <$2000 <$3000 <$4000 <$5000 <$10,000 All other Total Annual TTL $0.5M - $4 M JETS 22 127 262 187 126 117 19 423 1,618 2003 TURBOPROP 91 413 310 173 60 17 0 0 1,104 2,722 1,658 JETS 29 145 217 155 104 117 22 337 1,396 2004 TURBOPROP 79 336 300 147 57 27 0 0 1,004 2,400 1,461 Source: Velocity Group analysis with information from AvData, a JETNET Company; transaction estimates are based on Aircraft BlueBook® values. Table 2: VLJ Operating Cost Comparison Price Hourly Variable Costs Annual Fixed Costs Cost Per NM Cost per Seat NM Ratio of Eclipse Cost per NM to Citation S/II Cost per NM ECLIPSE 500 $1,093,626 $401 $267,579 $3.77 CITATION S/II (1988) $2,400,000 $1,203 $361,868 $6.68 $0.94 56% $0.95 Source: Conklin & deDecker Spring 2005, Book Depreciation, with adjustments for Eclipse co-pilot, fuel to $3 per gallon, Eclipse with 4 passenger seats, aircraft utilization at 500 hours per year. briefly sets aside the added application of air taxi to which I shortly will return. In 2005, there were 750 new jets and 365 new turboprop aircraft delivered worldwide (GAMA General Aviation Airplane Shipment Report, End-of-Year 2005). But this data is not the proper context for assessing prospects for VLJ’s; rather one needs to consider the new and used market that totaled almost 3,500 transactions in 2005. This market includes no new turbofan aircraft that list for less than $4 million (there are none as yet), but does include used turbofan aircraft as well as new and used turboprop aircraft. TABLE 1 supplies estimated information by price category for two recent years. VLJs Supply Turbine Aircraft Buyers with a New, Low-Cost Alternative VLJs will provide the approximately 1,500 annual turbine aircraft buyers in the $0.5 managing the skies • july/august 2006 | 13 million to $4 million price category a new choice – a new, factory-supported, lowcost light jet of modest capability. The trade-off is not unlike what buyers consider when purchasing a car. Do you want large capacity for lots of folks and luggage as well as comfort traveling long distances at a high acquisition and operating cost, including used car headaches? Or, might you be interested in a new, low-cost alternative? Although the alternative is smaller, it also is highly economical and free of problems for the duration of its warranty period. Intuition and some survey work show that the VLJ will capture a share of the existing market or approximately a 20 percent share of sales in the $0.5 million to $4 million price category. Thus, sales of 300 units a year can be expected from existing customers without depending on entirely new operating models such as air taxis. Can there be additional sales to piston-engine buyers? Absolutely! User surveys identify interest in VLJ’s by buyers of twin-piston aircraft, too. We have found about 30 percent of twin piston buyers would seriously consider a VLJ. When applied to the 140 piston twins delivered in 2005, up to 40 additional VLJ purchases per year can be identified. In summary, we identify the private (non-air taxi) VLJ market to average 340 aircraft per year, or 3400 over 10 years. We expect a higher rate in the first few years as new models are certified and launch-orders are delivered, and lower rates in later years once the initial pipeline is filled. Taxi or Charter: It Is Mostly About the Economics According to the National Air Transportation Association (NATA), there are 3,000 on-demand air taxi operators in the US operating more than 11,000 aircraft. Separately, the Air Charter Guide® recently estimated that there are approximately 2,000 jets in the US charter fleet. Here-in lies the first hurdle for air taxis: what’s new? With all this existing air taxi activity, why hasn’t the business already taken-off? In reply, two points quickly can be made: branding and economics. Of the 3,000 NATA-identified air taxi 14 | managing the skies • july/august 2006 Figure 1 No. of Passenger Markets without Nonstop Air Services (300-600 Statute Miles) – 2005 businesses, NATA reports 90 percent are classified as small businesses. From other estimates, only about 330 of these firms are considered “first tier” in that they meet the criteria of professional independent audit groups (such as ARG/US and Wyvern). Which leads us to the first point: the national branding of charter or air taxi services has been woefully inadequate. Despite the professionalism in larger firms, the public view (especially in medium and smaller communities without the large chain operations) unflatteringly links charter, air taxi, and the local “mom and pop” FBO operation. In this environment, creating brand awareness by emphasizing safety, professionalism, cost-competitiveness, and business substance on a regional or national basis can indeed generate a new level of market interest. Can a new air taxi operation utilizing VLJ’s deliver on the cost premise? It will indeed be challenged as Vaughn Cordle suggests with future fees and cost creep, but the VLJ provides an attractive starting point. Consider the comparison in Table 2. Using information prepared by Conklin and deDecker’s “Aircraft Cost Evaluator” (April 2005 edition), the costs of the Eclipse 500 VLJ are compared with a typical existing light jet used in charter operation, a Cessna Citation S/II. As indicated, the cost of operating the Eclipse 500 per aircraft (nautical) mile appears to be slightly over half (56 percent) that of the Citation (at $3.00 per gallon fuel and 500 hours of annual utilization). If the S/II’s seats were filled, there would be little difference in per seat cost. But with four or fewer seats occupied, the per-seat cost reduction is significant. A VLJ operated by a well-branded entity adds a product with both a new image and new cost to the air travel mix. This opportunity is not restricted to air taxis. Existing charter operators may use the VLJs to expand business by emphasizing new, lower-cost services. Other models can be developed such as fractional VLJ plans as announced by London, Ontario-based OurPLANE. We can expect competition to lead to more such innovations and alliances; the exact outcome and business mix will be determined by marketplace dynamics enabled and impelled by these new, lower-cost aircraft. If There is Demand for Cars and Buses, There Likely is Demand for Air Taxi Service I share with Vaughn angst about the source of the air taxi passengers. Can I go to my corporate travel department and obtain approval with the good news that for a www.faama.org mere doubling (tripling?) of my air fare, I can increase the quality of my life (and become a more productive employee) by undertaking a two day trip in only one day? It remains difficult for those of us who have not conducted extensive customer surveys to identify exactly who these riders will be. If there is demand for cars and buses, it seems there should be demand for a taxi service in between. Consider first the aerial equivalent to buses and cars: the aerial bus traffic. In the US, there were approximately 452 million one-way domestic airline trips conducted in 2005 (not enplanements of which there are more, thanks to the hub-and-spoke system). Of this total, 41 million are higher yield, by which I mean the passenger is traveling on a first class, discounted first class, business class, discounted business class, or full-fare coach ticket based on DOT’s 10 percent ticket sample. These are passengers who pay a premium for added comfort, privacy, or the need to depart without advanced planning. On average, these passengers pay $0.25 to $0.35 per mile, with coach fares on some routes exceeding a dollar a mile. The aerial equivalent to the car is the existing business jet and turboprop fleet. There are approximately 16,800 of these aircraft in the US (according to AvData Inc, a JETNET Company for NBAA’s Business Aviation Fact Book). Though not tallied, using a variety of industry sources, we estimate approximately 13 million one-way trips are conducted annually on the turbine-powered business aircraft in active use. Cost of these trips depends on how many seats are occupied, but at average load factors these aerial auto’s cost from $1.40 per seat nautical mile (NM) up to $7.00 per seat NM; at low loads, the price can go to $35 per seat NM. An on-demand taxi-like service at $1.50 to $3.00 per seat mile (independent of load factor) would fit between the existing aerial bus and car alternatives. And demand should likewise if service is comparable. It would appear that this lower-cost alternative suggests www.faama.org an air taxi opportunity of over 13 million passengers per year. This would be the case if an air taxi system were fully available on a national basis. Yet, on this assumption, I have my doubts. Sweet Home Alabama, or Do I Have Georgia on My Mind? All states are not equal in their prospects for supporting an air taxi-type service. We have looked at the ability to fly directly from one commercial service airport to another – between all commercial hubs and non-hubs. To paraphrase Willie Sutton and his rationale for robbing banks, passengers will travel to locations because there are others for them to meet. Measures of commercial airport-to-airport connectivity provide one useful index of the connecting locations to or from which people want to travel. We have tallied the number of commercial-service airports within 300 to 600 miles of each commercial service airport in the 48 contiguous states to which one can not fly directly. Thus, the higher the tally, the poorer the connectivity with other cities within this distance band. The results are provided in FIGURE 1. The analysis indicates that Georgia’s airports have the poorest connectivity to other airports and cities in this range. Another way to phrase this finding is that if any state needed some form of direct, supplemental, point-to-point service, that state would be Georgia. And the states surrounding Georgia. How Many Angels Can Dance on the Head of a Pin? So we return to the question of the air taxi and VLJ market; we can use some of the above findings for a rough estimate. The prime geography for an air taxi system appears to be Georgia and its five bordering states. (Other influences such as income might be added for a more detailed analysis.) These states comprise 17 percent of the US population (2000 Census). We combine the assumption that a national air taxi fleet might generate a volume of passengers equal to the number making trips on today’s jet and turboprop fleet and the six-state population share. The result is a demand estimate of about 2 million trips per year from this six-state region for an air taxi type service. If one operator (or more) could serve this with average loads of 1.5 passengers per trip and 5 trips per aircraft per day, a fleet of 750 air taxi’s could satisfy this prime region’s requirements, or twice this number with utilization restrictions of 1,400 hours per aircraft per year. Order of magnitude, VLJ demand for air taxi services might be about one-half that of the private demand first described. The resultant total is 5,000 aircraft over 10 years: higher earlier and lower in the later years. The middle estimates cited by Bill appear plausible from this review. But even at this level, Vaughn’s warning “this volume does not support the number of VLJ manufacturers that are entering the space” remains applicable. There are far too many participants (12 companies!) for sales under any reasonable scenario. We saw a similar phenomenon following deregulation in the early 1980s when eight manufacturers jumped into the 30–60 seat regional/commuter turboprop market. Remember British Aerospace, ATR, CASA/IPTN, deHavilland, Dornier, Fokker, Saab, and Short Brothers? Only two of these survive today on civilian sales. Once again the excitement of filling the infamous “hole in the market” attracts more participants than can be financially supported. A lot has been written on the air taxi concept. And much analysis has been undertaken on both market opportunity and operating procedures. The industry is at the point where delivery of the promised product is the next test. Will the buzz from early users convey enthusiasm and excitement, or will they be disappointed and deprecating? Will the volumes emerge enabling operators to make the returns anticipated? Æ Gerald W. Bernstein is a founding partner of The Velocity Group aviation consultancy with offices in Washington DC, San Francisco, Orlando, and Tokyo. Mr. Bernstein has over 25 years experience in the development of business strategies for manufacturers of all types of civil aircraft, and for key component suppliers. Mr. Bernstein is immediate past Chairman of the U.S. National Research Council’s Transportation Research Board Aviation Economics and Forecasting Committee. He is an instrument-rated private pilot, and is listed in Who’s Who in America. managing the skies • july/august 2006 | 15