Socrates v. Confucius: An Analysis of South Korea's Implementation

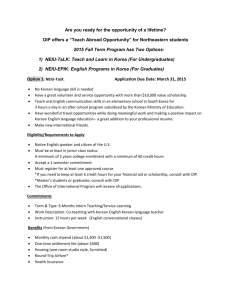

advertisement