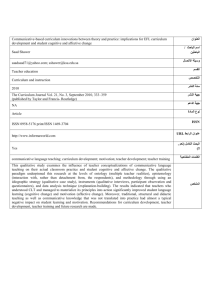

Journal of International Business and Economic Affairs - ECO-ENA

advertisement