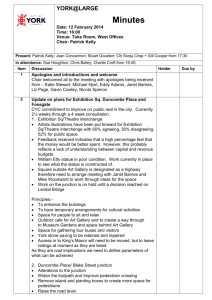

Top Acc_06_book.indb

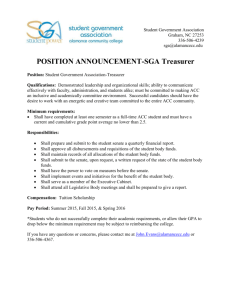

advertisement