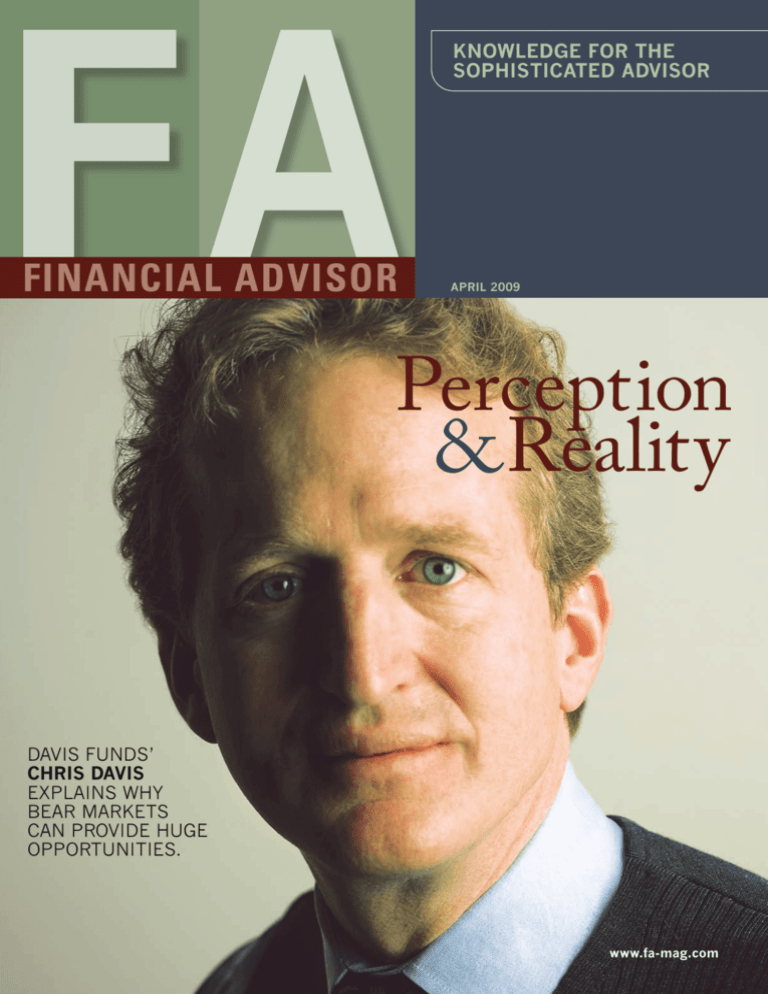

FA

financial advisor

KNOWLEDGE FOR THE

SOPHISTICATED ADVISOR

april 2009

Perception

& Reality

davis funds’

Chris Davis

explains why

bear markets

can provide huge

opportunities.

www.fa-mag.com

Perception

&reality

davis funds’ Chris Davis explains why bear markets

can provide huge opportunities. by evan simonoff

financial advisor magazine | april 2009

www.fa-mag.com

Cover Story

photographs by chad murray

april 2009 | financial advisor magazine

F

For much of his professional life, Chris Davis

found himself thinking, with a degree of jealousy, of stories

his father and grandfather would tell him about purchasing

shares in companies like Johnson & Johnson for 12 times

earnings with a 3.4% dividend back during the great bear

markets of the last fifty years.

Now that he could take advantage of a similar opportunity, it doesn’t feel like the incredible bargain basement it was

a half century ago. “The hardest thing is that every day the

market tells you you’re an idiot,” Davis says. “We’re nine years

into what will almost certainly become the worst decade for

stocks, including the 1930s (after the 20%-plus 1999 returns

is replaced with 2009).”

After learning about investing from his grandfather,

a former New York state insurance commissioner, diplomat

and an investor who parlayed $100,000 into $800 million1,

and his father, the legendary Shelby Davis, Chris Davis started in the business as an analyst in the middle of the 19821999 bull market in 1989. Until recently, he had never run

money in this kind of environment. “My grandfather used to

say you make most of your money in bear markets. You just

don’t realize it at the time,” Davis recalls.

Many investors like to buy great companies for the long

term, even if some are questioning that strategy today. But

finding an attractive entry point is critical to generating positive returns over a decade.

Pick a company like Johnson & Johnson or Procter & Gamble that is growing at 10% a year and paying a 3% dividend,

Davis says. “If you buy the stock at 10 times earnings and it

goes to a 15 P/E over a decade, that’s an 18% return,” he notes.

“If you buy it at 20 times earnings and the multiple goes to 15

over 10 years, your return is 6%.”

Davis isn’t about to call a bottom, something he considers a

“terrible thing to do.” People should be excited at the chance to

buy stocks on the cheap, but if they truly were, equity markets

would be a lot higher. At the same time, nobody has rung the

proverbial bell or published a magazine cover proclaiming “The

Death of Equities,” as Business Week did in 1979.

Davis notes that when the magazine ran that cover story, the

stock market had nearly doubled off its 1975 low, yet no one

felt very good about it. Interviewed in late February, he says it’s

been a long time since he heard “a single rosy forecast for the

next five or ten years.”

What is so pervasive today is the chasm between risk and the

perception of risk. Flying in airplanes in the pre-9/11 era was

much riskier than it is today. People just didn’t realize it.

Likewise, Davis observes that the safety of many small cars is

greater than SUVs, despite what SUV marketers may tell you.

“If a Toyota Camry collides with an SUV, you may have a better chance surviving in the SUV, but more people die in SUVs

than Camrys,” he continues. “People drive faster in the rain in

an SUV but they don’t brake any better.” If you really wanted

to reduce auto fatalities, he suggests putting a sharp steel spike

on the driver’s wheel.

The waves of selling triggered last fall by the collapse of Lehman Brothers struck him as irrational, as did the bull market

capitulation that afflicted some normally rational investors in

early 2000 when they stopped trying to fight the tidal wave and

piled into Cisco Systems at $80 a share. Six months ago, giant institutions found themselves locked in illiquid hedge-fund

and private-equity investments and some were forced to sell

their publicly traded, blue-chip stocks—at any price. “It was

pawnshop economics; sellers weren’t asking what the underlying businesses were worth,” Davis says. Fortunes, he continues,

are made at times like this when there is very little visibility.

Over the last ten years, the Standard & Poor’s 500 index has produced annual returns of between -2% and -3%,

depending on what day one measures. Can it do that for

another five or ten years?

“Possibly,” Davis acknowledges. “But if you look at every

ten-year period [when the S&P 500 return was below 5%]

and then look at the next ten years, the average annualized

return was about 13%, and the worst was 7%. The idea that

equities will underperform risk-free alternatives is a very low

probability. People are paying an irrational premium for the

perception of safety.”

Davis Advisors’ largest fund, the Davis New York Venture

Fund, has a reputation as having a strong interest in financial

shares. However, Davis explains their real objective is to find

growth companies in disguise, which often leads them to financial companies.

A classic example is Progressive Insurance, an auto insurer

that has grown at 18% to 20% for the last 20 years. “In almost

any other industry it would normally trade at 20 to 30 times

earnings, but Progressive trades at 12 times,” Davis says.

All financials are not the same, as Davis is quick to point

out. An investor who held a finance company, a retailer and a

capital goods concern might think they have the foundation of

a diversified portfolio, but if those companies happened to be

Countrywide, Home Depot and Toll Brothers they would have

been sadly disappointed in 2008.

In 2008, the Davis New York Venture Fund lost 40.0% of

1While

Shelby Cullom Davis’ success forms the basis of the Davis investment discipline, this was an extraordinary achievement and other

investors may not enjoy the same success.

financial advisor magazine | april 2009

www.fa-mag.com

Cover Story

its value, not far from the S&P 500’s 37% decline.2 But other

funds with excellent long-term track records, like Dodge &

Cox Stock Fund, fared much worse. Many gave back half their

NAV or more to the merciless market.

Davis’ funds take the long view and they are evaluated on

10-year performance figures. It so happens that the Davis New

York Venture Fund posted 10-year annualized total returns

of 1.24%, but beating the S&P 500, which fell 1.38% over 10

years, isn’t a source of satisfaction when returns are so low.

This equity market hasn’t spared any of the few winners,

and Davis is far too grounded in reality to take satisfaction

from outperforming some former superstars. “About 44% of

all managers in the top quartile over the last decade were in

the bottom decile for a three-year period,” he notes. In other

words, gloat at your own risk.

Despite their funds’ sizable setback last year, investors in

Davis’ funds managed to survive

the worst of the subprime tsunami

better than many others. Like survivors of a coal mine disaster, they

managed to live to fight another

day, while many rivals that saw

more than half their capital vaporized remain trapped below the

earth living off what oxygen rescuers can thread to them through

various tunnels.

Going into 2008, Davis and his

team knew that credit was too easy

and they assumed there would be

a downturn. Despite their financial exposure, they managed to

sidestep the first six victims—

Countrywide, Bear Stearns, Lehman, Fannie, Freddie and WaMu.

They weren’t so lucky with AIG,

once believed to be the strongest

financial services firm on earth. It

cost the fund a cumulative 6% over

the last five years. The fund also had

a long-term investment in Merrill

Lynch, which it had acquired at an

average cost of $35 a share. Right after its acquisition by Bank of America was announced at $29 a share,

the funds started selling. Say what

you will about former Merrill CEO

John Thain, but Davis notes he did “a

masterful job” at convincing Bank of

America to pay $29 a share.

The space on the wall between

Davis’ office and co-manager

Kenneth Feinberg is reserved for documenting their mistakes. In fact, it’s called The Mistake Wall.

In a ten-page letter to shareholders in February, the two

portfolio managers devoted nearly two pages to discussing

their AIG mistake, which cost investors three times more

than any other. “We owe our shareholders an accounting of

our mistakes,” Davis says.

Condensing their explanation, Davis and Feinberg conceded

that they—along with the entire AIG management team—

vastly underestimated the destructive potential of a certain derivative known as a credit default swap (CDS) and how much

collateral these contracts might require the insurer to post. Furthermore, they assumed that, since AIG was an insurance company, the classic run-on-the-bank scenario that brought down

Bear Stearns and Lehman was not a life-threatening danger.

But AIG had a big securities lending operation, and while they

2Performance

discussed in this article represents Class A shares, not including a sales charge as of 12/31/08, unless otherwise specified. Past

performance is not a guarantee of future results.

april 2009 | financial advisor magazine

had huge cash reserves, regulations did not allow them to upstream the cash from subsidiaries to the parent.

Perfect storms clearly possess higher odds than the vast majority of investors thought. “Nouriel Roubini was right and we

weren’t,” Davis says. “But the reaction that we should just raise

cash doesn’t make sense. It was like you are crazy if you don’t

own Cisco in 2000. Everyone wants to do today what they wish

they had done a year ago.”

Nonetheless, living through the last 18 months has, at

times, been a learning experience, even for sophisticated investors. The idea that a triple-A-rated company like General

Electric might have been unable to roll over its short debt and

saw its survival threatened stunned him. “We always assumed

credit would always be available to high-quality credits,” he

notes. This assumption, embedded in all of modern finance,

now needs to be revisited.

While Davis’ team members are meticulous students of accounting, they always viewed it as a way to provide different

takes on reality rather than something that directly impacts real-

public companies. Davis and his team expend a great deal of

effort trying to get at “the underlying reality,” examining such

adjustments as pension income/expense, depreciation versus

maintenance capital spending, nonrecurring charge-offs, inventory and mark-to-market adjustments, tax rates and the

cost of equity compensation.

Davis’ team likes to break their portfolio into four components. They label the first group camels, because these are

companies that can spend an eternity in the desert without

water, or rather capital. This list includes Procter & Gamble,

Costco and Microsoft.

Another holding in this category is Google. Davis watched

the company’s profits and shares soar in the years immediately

after its IPO. During that period, they also heard executives at

auto insurers like Progressive and Geico enthuse about the efficiency of using Google as an advertising vehicle. When Google

shares dropped more than 50% from their all-time high last

year and at less than 12 times their estimate of “owner earnings,” Davis’ team purchased it.

while davis’ team members are meticulous

students of accounting, they always viewed it

as a way to provide different takes on reality

rather than a way to directly impact reality.

ity. When rating agencies began to include equity prices, markto-market accounting and credit default swap spreads in their

calculations, the game changed. Now a downgrade can make a

company sell assets, even when there is no market for them. “Allowing the shameful explosion of the CDS market” as a place to

speculate on companies’ demise was a disgrace, Davis thinks.

Still, Davis, Feinberg and the rest of their portfolio management

and research staff dodged more bullets than many mutual funds—

for several reasons. As investors, they like to step back and look

at investments in ways that give them a degree of detachment to

avoid developing biases or getting locked into their convictions.

Speaking at a Morningstar conference several years ago,

Davis flashed a PowerPoint shot of some of the metrics they

consider important, then showed the numbers of two businesses that looked very similar. One happened to be a packaging

manufacturer, while the other was a railroad.

Scrambling various metrics might prove an interesting intellectual exercise, but what was the point? The point was that

numbers tell only part of the story, as CEOs have been heard

to quip that they can drive fleets of trucks through the holes in

generally accepted accounting principles.

Any advisor who owns his or her own firm knows that there

are legitimate ways to make their business look more or less

profitable, and those opportunities are magnified at huge

financial advisor magazine | april 2009

The second part of their portfolio centers on companies that

tend to be disciplined, opportunistic and well-positioned to

take advantage of sudden changes in the capital markets. Some

of these companies like Dun & Bradstreet and Loew’s Corp.

are also disciplined share repurchasers. Davis notes that in an

environment characterized by severe dislocations like those of

the last six months, many managements get scared and back off

stock buybacks at just the wrong moment.

The third group focuses on companies that operate in areas

where headline risk is the highest. Not surprisingly, this group

is heavy on financial services and includes Progressive Insurance

and Bank of New York Mellon, which is fundamentally more

of a transaction processor than a bank, as well as such franchise

financials as JP Morgan, Wells Fargo and American Express.

Straddling groups two and three is Berkshire Hathaway. “The

headlines on Berkshire are likely to get worse, but they went

into this crisis with $50 billion in cash and they are well-positioned to take advantage of this crisis,” Davis says. Recently, his

funds joined with Berkshire to invest in senior securities in two

companies whose equity they already own, Sealed Air and Harley Davidson. The securities yield 12% and 15%, respectively.

The final group revolves around companies positioned to benefit from the powerful emergence of a global middle class. “The

odds of China growing at 7% or 8% for the next decade are still

www.fa-mag.com

Cover Story

pretty high,” Davis says. Energy stocks like Occidental, ConocoPhillips, EOG and Devon dominate this group. Davis hasn’t

bought any oil service companies yet, “but we are looking.”

Does Davis worry about the rise of the anti-Wall Street,

pseudo-populist, anti-business environment in the wake of the

most severe collapse of the financial system in 80 years? Of

course. “People hear that and say, ‘I won’t invest,’” he says. “The

opportunity to invest comes about because of things like this.”

The odds are strong that taxes will be higher, inflation will

be higher, while productivity and profit margins will be lower.

Between 1975 and 1980, America experienced high unemployment, double-digit inflation and declining respect around

the world, but also in those years, stock prices nearly doubled

while small-cap stocks sparkled.

Looking into the next decade, Davis thinks it’s a “near certainty” the environment for equities will be superior to the

last decade. “The question isn’t what is going to happen; it’s

what is discounted,” he says.

The conventional wisdom that private equity funds and

hedge funds are the only logical buyers for toxic assets and other

opportunities that may arise from the crisis leaves him irked.

“Why doesn’t anyone ever mention public equity?” he asks.

Davis won’t draw a direct correlation between the headfirst

rush of institutional investors into alternative investments over

the last decade and the subpar returns so many of them experienced. But he is quick to note that the result was a move to less

liquidity, higher fees and more leverage, all of which reduced

returns and exacerbated the subprime debacle.

Ultimately, his firm’s goal is to create a portfolio that can

compound over a generation, a portfolio with offensive and defensive elements. He is also acutely aware that his shareholders

differ from those of hedge funds, as when his barber asked him

if he knew how many haircuts it would take him to recoup the

$1,000 he lost in Davis’ fund.

“What we do has life-changing consequences for our shareholders,” he reflects, noting that advisors deal with these issues

on a constant basis. “If you are wired with a stewardship gene,

you feel terrible right now.” Legal Disclosure:

Annualized Total Returns as of March 31, 2009

Davis New York Venture Fund Class A

with a maximum 4.75% sales charge

1 Year

5 Years

10 Years

–44.70%

–6.22%

–0.85%

The performance presented represents past performance and is not a guarantee of future results. Total return assumes reinvestment of dividends and capital gain distributions. Investment return and principal value will vary so that, when redeemed, an investor’s shares may be worth

more or less than their original cost. The total annual operating expense ratio for Class A shares as of the most recent prospectus was 0.85%. The

total annual operating expense ratio may vary in future years. Returns and expenses for other classes of shares will vary. Current performance

may be higher or lower than the performance quoted. For most recent month-end performance, visit davisfunds.com or call 800-279-0279.

This reprint is authorized for use by existing shareholders. A current Davis New York Venture Fund prospectus must accompany or precede this

reprint if it is distributed to prospective shareholders. You should carefully consider the Fund’s investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses

before investing. Read the prospectus carefully before you invest or send money.

DAVIS DISTRIBUTORS, LLC (DDLLC) paid Financial Advisor Magazine their customary licensing fee to reprint this article.

Financial Advisor Magazine is not affiliated with DDLLC, and DDLLC did not commission Financial Advisor Magazine to create

or publish this article.

This reprint includes candid statements and observations regarding investment strategies, individual securities, economic and market

conditions; however, there is no guarantee that these statements, opinions or forecasts will prove to be correct. These comments may

also include the expression of opinions that are speculative in nature and should not be relied on as statements of fact.

Davis New York Venture Fund’s investment objective is long-term growth of capital. There can be no assurance that the Fund will

achieve its objective. Davis New York Venture Fund invests primarily in equity securities issued by large companies with market

capitalizations of at least $10 billion. Some important risks of an investment in the Fund are: market risk: the market value of shares

of common stock can change rapidly and unpredictably; company risk: the market value of a common stock varies with the success

or failure of the company issuing the stock; financial services risk: investing a significant portion of assets in the financial services

sector may cause a fund to be more volatile as securities within the financial services sector are more prone to regulatory action in the

april 2009 | financial advisor magazine

financial services industry, more sensitive to interest rate fluctuations, and are the target of increased competition; and foreign country

risk: companies operating, incorporated, or principally traded in foreign countries may have more fluctuation as foreign economies

may not be as strong or diversified, foreign political systems may not be as stable, and foreign financial reporting standards may not be

as rigorous as they are in the United States. As of March 31, 2009, Davis New York Venture Fund had approximately 11.4% of assets

invested in foreign companies. See the prospectus for a complete listing of the principal risks.

The information provided in this reprint should not be considered a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any particular security. As

of March 31, 2009, Davis New York Venture Fund had invested the following percentages of its assets in the companies listed: AIG,

0.07%; American Express, 2.05%; Bank of America, 0.08%; Bank of New York Mellon, 3.27%; Berkshire Hathaway, 4.83%; Cisco

Systems, 0.69%; ConocoPhillips, 2.84%; Costco Wholesale, 3.97%; Devon Energy, 2.70%; Dun & Bradstreet, 1.61%; EOG Resources,

2.64%; Google, 1.78%; Harley Davidson, 1.33%; Johnson & Johnson, 1.11%; JPMorgan Chase, 3.72%; Loews, 2.08%; Microsoft,

2.02%; Occidental Petroleum, 3.16%; Procter & Gamble, 1.73%; Progressive, 2.22%; Sealed Air, 2.01%; Wells Fargo, 2.79%.

Davis Funds has adopted a Portfolio Holdings Disclosure policy that governs the release of non-public portfolio holding information.

This policy is described in detail in the prospectus. Visit davisfunds.com or call 800-279-0279 for the most current public portfolio

holdings information.

This reprint is not a solicitation for the Dodge & Cox Stock Fund.

Broker-dealers and other financial intermediaries may charge Davis Advisors substantial fees for selling its products and providing

continuing support to clients and shareholders. For example, broker-dealers and other financial intermediaries may charge: sales

commissions; distribution and service fees; and record-keeping fees. In addition, payments or reimbursements may be requested

for: marketing support concerning Davis Advisors’ products; placement on a list of offered products; access to sales meetings, sales

representatives and management representatives; and participation in conferences or seminars, sales or training programs for invited

registered representatives and other employees, client and investor events and other dealer-sponsored events. Financial advisors should

not consider Davis Advisors’ payment(s) to a financial intermediary as a basis for recommending Davis Advisors.

A study is cited that examined the percentage of top quartile large cap equity managers whose performance fell into the bottom half,

quartile or decile for at least one rolling three-year period from January 1, 1999–December 31, 2008. 163 managers from eVestment

Alliance’s large cap universe whose 10 year average annualized performance ranked in the top quartile were examined. 97% fell into

the bottom half; 77% fell into the bottom quartile; and 44% fell into the bottom decile. The source is Davis Advisors. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Over the last five years, the high and low turnover ratio for Davis New York Venture Fund was 16% and 3%, respectively.

The S&P 500® Index is an unmanaged index of 500 selected common stocks, most of which are listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The Index is adjusted for dividends, weighted towards stocks with large market capitalizations and represents approximately

two-thirds of the total market value of all domestic common stocks. Investments cannot be made directly in an index.

After July 31, 2009, this material must be accompanied by a supplement containing performance data for the most recent

quarter end.

Shares of the Davis Funds are not deposits or obligations of any bank, are not guaranteed by any bank, are not insured by the FDIC

or any other agency, and involve investment risks, including possible loss of the principal amount invested.

Item #5142 4/09 Davis Distributors, LLC, 2949 East Elvira Road, Suite 101, Tucson, AZ 85756, 800-279-0279, davisfunds.com

Opinions

and estimates contained in this article are subject to change without notice, as are statements of financial

market trends, which are based on current market conditions.

of

Financial Advisor Magazine. All

rights reserved.

This article originally appeared in the April 2009

Charter Financial Publishing Network, Inc.

issue