Report on the Practice of Forced Marriage in Canada: Interviews

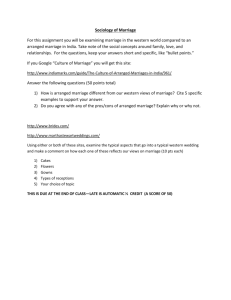

advertisement