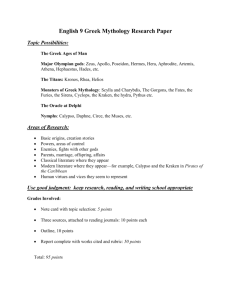

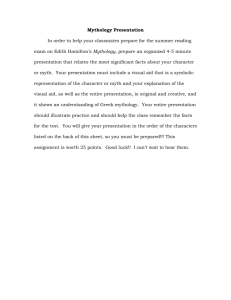

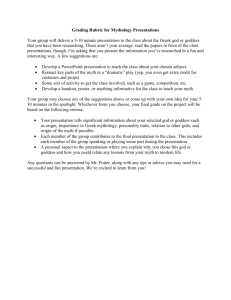

Greek mythology - Santa Rosa County School District

advertisement