OEV 210 - The Open University of Tanzania

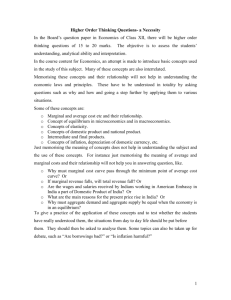

advertisement