Indo-European Studies 2

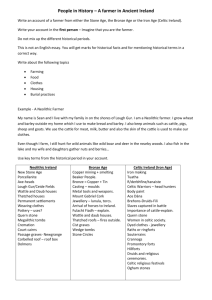

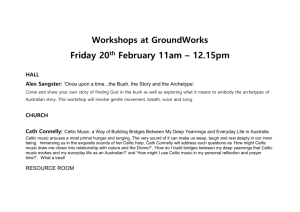

advertisement

Indo-European Studies 2 Kirk S. Thomas ADF Member no. 2296 Clergy Training Program Note: Where two cultures are requested, you must choose from each regional focus above. Question #1: Describe and compare the image of kingship in two cultures, paying special attention to the consecration of a king. (100 words for each culture) Western (Ireland) Kingship in ancient Ireland was closely tied to the ideas of Sovereignty (see question 5 below) and that of the king’s fir, or ‘truth’ (which is also rightness and judgment) and which is all about maintaining the social order. The king must be fair, be reciprocal in dealings with others, as well as generous, capable and truthful (among other things). (Koch, Vol.3, 1060-1063 and Kelly, 611) The king must also not be ‘blemished’. (Ó hÓgáin, 170-171) Nuada lost the Kingship of the Tuatha de Danaan because he lost a hand in battle, thus making him incomplete. (Koch, Celtic Culture, Vol. 3, 1061) There is a story of the consecration ceremony for a king in Cenil Cunill (in Ulster) told by Giraldus Cambrensis. The king has intercourse with a white mare, which is then sacrificed, and the king would bathe in the broth made from the mare’s flesh, eating the flesh (and sharing it with his subjects) and drinking the broth with his mouth. If true, this could be a rite of sovereignty. (Forester, 77-78) Eastern (Vedic India) The consecration rites for a Vedic king involved coitus, but there it was between the queen and a sacrificed (dead) horse (for the asvemedha) or between the queen and a sacrificed (dead or dying) youth (for the purusamedha). Somehow, in India, the joining of king and land was instead moved to the queen. Puhvel speculates that this is due to the ritual becoming cut off from the myth that made it significant. (Puhvel, 270-271; 273) Here, as in Ireland, the role of the king was to maintain the social order. He would oversee festivals and lead sacrifices for the betterment of all of society. These blessings were to go to the priesthood, royalty, cow, ox, horse, woman, chariot fighter, and youth. (Puhvel, 276) Question #2: Describe and compare the ritual use of intoxicating beverages in two cultures. (min. 100 words per culture) Western (Ireland) The name of the goddess Medb (who married many kings) comes from the Welsh word meddw, which means ‘drunk’ (Rees and Rees, 75) and which may be cognate with the PIE word, -medhu, which means ‘honey’ or ‘mead’. (Watkins, 52) Intoxicating beverages were used to convey sovereignty in ancient Ireland, in the form of the derg flaith (‘red ale’ or ‘red sovereignty’). Medb Lethderg was the daughter of Conán of Cuala, and no man could become king of Ireland unless the ale of Cuala came to him. (Rees, 75) The Irish king Conn, in a vision, sees the goddess Eriu (Ireland) who serves him the derg flaith, and then serves the cup to his descendents, all future kings, while her consort, Lugh, announces their reigns. Here, sovereignty is both the server of the drink, and the drink itself. (Rees, 76) 1 Eastern (Vedic India) As in Ireland, sovereignty in India is conveyed through an intoxicating drink, soma. Soma was made from the pressed leaves of a certain plant, and may have originally been related to, or connected with, honey and mead. (Brennemann, Jr., 58) The deified Soma was central to Vedic religion and has more hymns dedicated to Him (after Indra and Agni) than any other deity in the Rg Veda. It was drunk at sacrifices, and was believed to give immortality to both Gods and men. One hymn (VIII.48.3) states, (Maurer, 76) We have drunk the Soma. We have become immortal. We have gone to the light. We have found the gods. What shall hostility do to us now? What, O immortal, shall the malice of mortal do? Question #3: Describe and compare the disposition of the dead in two cultures (100 words per culture) Western (Gaul) If the classical commentators are to be trusted, the Celts believed that there was life after death, and one that reflected their social statuses on earth. Of Celtic belief in an afterlife, Diodorus Siculus (5.28) writes, (Koch, Celtic Heroic Age, 12) …the human spirit is immortal, and will enter a new body after a fixed number of years. For this reason some will cast letters to their relatives on funeral pyres, believing that the dead will be able to read them. In the late Hallstatt period of southwest Germany and eastern France, around 600-450 BCE, there existed a complex and very hierarchical chiefdom-type Celtic culture whose high-status graves were richly appointed. The graves of the ‘paramount chiefs’ show inhumation in wooden chambers accompanied by four-wheeled carts and horse harnesses, all filled with imported luxury goods including Greek and Etruscan drinking vessels of bronze and silver, and lots of gold jewellery and torcs. These prestige barrows are surrounded by less high-status barrows with fewer grave goods, and inserted into all these barrows were secondary burials of more common folks with far fewer grave goods. Those who had more got to take more with them. (Wait, 501) There was a change from inhumation to cremation burials in the Late Iron Age, but this need not imply a change in beliefs about death. In the cremation burials, grave goods would still be included, as Caesar states (de Bello Gallico 6.19), ‘The funerals, by the standards of the Gauls, are splendid and expensive. It is judged that all which was held dear [by the deceased] while alive should be put into the fire…’ (Koch, Celtic Heroic Age, 23) Eastern (Vedic India) The Rig Veda mentions both interment and cremation as methods of disposing of a body, but from the number of references, it would seem that cremation was more common. There is a hymn (X.16) specifically for a cremation funeral and it indicates that although Agni is called upon to burn the body, he is also asked not to consume the body utterly but to allow as much as possible to merge with the cosmic elements (‘May your eye go to the sun, your breath to the wind’) while delivering the dead person to the Fathers where he will live in eternal bliss (assuming he’s made his sacrifices, presumably). From Rig Veda X.16.11 we read, (Maurer, 258-260) May Agni, carrier off of the corpse, who shall worship the Fathers who thrive in the Rta, announce the oblations to the gods and to the Fathers! 2 Question #4: Describe and compare the role of the priest in two cultures (100 words per culture) Western (Gaul) The priests of the ancient Celts were called Druids. Caesar (6.13) tells us that there were two classes of men in Gaul who have rank and honor, the first being the Druids and the second being the ‘warriors with horses’ whom we can call the nobility. The Druids ‘intervene in divine matters; they look after public and private sacrifices; they interpret religious matters’. (Koch, Celtic Heroic Age, 21) Pomponius Mela (De Situ Orbis 3.2.18-19) writes that ‘They claim to know the size of the earth and cosmos, the movements of the heavens and stars, and the will of the gods.’ (Koch, Celtic Heroic Age, 31) Strabo (4.4.4) goes on to elaborate on the divisions of the Druid class, saying, (Koch, Celtic Heroic Age, 18) As a rule, among all the Gallic peoples three sets of men are honoured above all others: the Bards, the Vates, and the Druids. The bards are singers and poets, the Vates overseers of sacred rites and philosophers of nature, and the Druids, besides being natural philosophers, practice moral philosophy as well. Eastern (The Hittites) The king administered the Hittite religious cult, with the priests under him and subject to his authority. The kings and royal family also functioned as priests and participated in the main festivals of the year. Since the safety of the kingdom and of the king depended on propitiating the Gods correctly and in quantity, numerous temples were built and many festivals had to be celebrated with food, drink, music, dance, acting and wrestling, and the priests were charged with organizing and overseeing all this activity. (Taggar-Cohen, 3) There were three main types of male priest. The Sanga priests were at the top of the hierarchy and would be the most powerful, and they served the Hattien-Hittite deities (as opposed to the local Hurrian deities). (Taggar-Cohen, 165) The Sanga priests were followed by the Gudu priests, who served in ritual situations where they would assist the king, queen and princes in performing certain rituals. They also served the Hattien-Hittite deities. (Taggar-Cohen, 274) These are followed by the Temple Men, who assist in maintaining the temples and ritual utensils, are responsible for the purity of the place, and who organize festivals. (Taggar-Cohen, 308-309) There are also two types of priestess in this hierarchy. The Sanga priestess is often seen in ritual in the presence of the king, queen or other priests, and the deities they serve are Hittite ones, often the female deities, as well as some Hurrian deities. The second type of female priest, the Ama.Dingir priestess, appears to be very similar to the Sanga priestess, and the name in later times seems to have replaced that of the Sanga. (Taggar-Cohen, 363-368) Question #5: Describe and compare the connection between horse and sovereign in two cultures (min. 100 words per culture) Western (Wales) In Wales, sovereignty was conferred on the sovereign through the feminine. In the First Branch of the Mabinogi, a mysterious woman appears to Pwyll, the unmarried Prince of Dyfed. She is riding a magical white horse that cannot be caught by others unless she wills it. After marrying him, she gives birth to a child who is stolen away and left at a noble’s house in lieu of a colt. The woman, Rhiannon (‘great queen’), has obvious equine associations and it is through her influence that her husband Pwyll rules fairly and well, learning to curb his natural impetuosity and think before acting. (Davies, 66-68) Later, in the Third Branch, it is only by marrying Rhiannon, a probable horse goddess, that Manawydan can come to rule Dyfed. In this branch, Rhiannon’s 3 equine associations are again emphasized in the punishment that she is forced to endure at the hands of the magician Llwyd, (Ford, 87) …and the collars of asses after they had been hauling hay, were around Rhiannon’s neck. Eastern (Vedic India) As I mentioned before in question #1, the coronation rite for a Vedic king involved his queen symbolically copulating with a sacrificed horse in the asvemedha rite. Unlike in Ireland, here the horse, as a theomorphic representation of sovereignty, mates with the queen instead of the sovereign king. Brennemann (66) suggests that the reason for this was that in Vedic India, this rite reflected the power of the masculine and the heavens (the first and second of Dumezil’s functions) as the divine source of sovereignty with the third function, represented by the queen, as the passive receiver. In any case, the horse in the rite represented sovereignty. Puhvel (275) suggests that India may have innovated here (rather than Ireland) because the asvamedha had become cut off from the myth that originally motivated it. The role of the transfunctional goddess Sarasvati had become significantly downgraded by Vedic times, and it is possible that though the king still presided over a horse festival with sexual overtones, over time it began to bring in other religious ideas that ended up with the queen mating with the horse instead of the king. Question #6: Describe and compare the importance of rivers in two cultures (min. 100 words per culture) Eastern (Vedic India) In Vedic India there was a goddess named Sarasvati (‘Rich in Waters’ or ‘Flowing’) who was also the mythical, sacred river of the same name. Unlike most of the class-conscious male Vedic deities, Sarasvati was transfunctional – a great female, earth-based goddess who was able to embrace and provide for all levels of society. (Puhvel, 62) This goddess was ‘River’, much as other deities might be ‘Land’ or ‘Sea’, and she is the river in the sky as well as on land. (O’Flaherty, 78, verse 25) Though she doesn’t show up much in the Rig Veda, there is one verse (1.164.49) that describes her importance to all mankind (O’Flaherty, 81, verse 49): 49 Your inexhaustible breast, Sarasvati, that flows with the food of life, that you use to nourish all that one could wish for, freely giving treasure and wealth and beautiful gifts – bring that here for us to suck. Western (Celtic Europe) Even before the rise of Celtic culture in Western Europe, rivers were the focus of cult activity. The Thames in Britain, for instance, received great quantities of metalwork in the Bronze Age, and this activity continued under the Celts. By the Iron Age, weapons such as swords, spears and daggers were the most popular offerings. In Roman Britain and Gaul, there were many river cults, usually concentrated at the river’s source. There was a temple complex at the source of the Seine sacred to the goddess Sequana, and the name of the consort of the god Sucellus, Nantosuelta, means ‘winding river’. Verbeia was probably the goddess of the River Wharfe in north-east England, and many shrines overlook rivers, such as the Temple of Nodens at Lidney, overlooking the Severn Bore. (Green, 138-141) 4 In both the Vedic and Celtic cases, rivers were considered important and worthy of worship. While we can’t be completely sure about the nature of Celtic river goddesses, they would seem to have traits similar to those of Sarasvati, i.e. bringers of life and wealth. Question #7: Describe and compare the interaction between king and virgin in two cultures (min. 100 words per culture) Eastern (Vedic India) In book 5 of the Mahabarata, Galava has been made a Brahmin by Visvamitra and in return is told to bring back 800 moon-white horses with one black ear. Dejected by this impossible task, Galava is taken to a potential donor, Yayati, who is down and out at the moment, but who offers Galava his daughter Madhavi instead. Galava decides to sell her for the 800 horses, but is unable to find anyone who has enough of them. Luckily, Madhavi has renewable virginity, so she ends up sleeping with (and bearing sons to) three men, collecting 600 of the horses, which turns out to be all the horses of this kind in existence. Galava then offers Madhavi to Visvamitra for one night in lieu of the remaining 200 horses, and thus discharges his debt. The point of this is that the recurring virgin Madhavi ends up being the mother of four kings, all of who have later roles in the tale. (Puhvel, 257-259) And these boys were the sons of kings who had been childless. Madhavi is not Sovereignty herself, but sovereignty passes through her to the four young kings. (Brennemann, 69) Western (Welsh) In India, as we have seen, the king is dependent on the virgin for continuation of the kingship. In Wales, the king’s very life depends upon the virgin. In the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi, the virgin Goewin is Math’s footholder because, (Ford, 90) In those days, Math son of Mathonwy could only live while his feet were in the lap of a maiden – unless turmoil of war prevented him. The implication here is that Math’s geis prevented him from stirring from Goewin’s presence unless a war was declared. Later in the tale Goewin is raped, and therefore no longer able to function as the virginal footholder, so Math searches for a replacement. His nephew Gwydion suggests he try out Gwydion’s sister, Aranrhod, for the role of virgin. When Aranrhod arrives at Math’s palace, he has her step across his magical staff, and when she does so, two baby boys fall out from under her dress, proving her lack of virginity. The tale then goes on to other plots concerning one of the boys, and we never hear if Math finds his virgin, though presumably he must as he appears again, hale and hearty, later on in the tale. It is also interesting that Math marries the violated Goewin long before the episode with Aranrhod. We don’t hear if Goewin bears him any sons, but one might speculate that she could be a vague memory of the Madhavi type goddess who gives sons to childless kings. 5 Bibliography Brennemann, Jr., Walter L. “The Drunken and the Sober: A Comparative Study of Lady Sovereignty in Irish and Indic Contexts” in Grepin, John and Edger C. Palomé, editors. Studies in Honor of Jaan Puhvel, Part 2, Mythology and Religion. (Washington, DC: Journal of IndoEuropean Studies, 1997) Davies, Sioned. The Four Branches of the Mabinogi: Pedeir Keinc y Mabinogi (Llandysul, Wales: The Gomer Press, 1993) Ford, Patrick K., translator and editor. The Mabinogi and Other Welsh Tales (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: The University of California Press, 1977) Forester, Thomas, trans. Giraldus Cambrensis: The Topography of Ireland (Cambridge, ON: In parenthesis Publications, Medieval Latin Series, 2000) Green, Miranda. The Gods of the Celts (Dover: Alan Sutton Publishing Inc., 1986, preprinted 1993) Kelly, Fergus, editor. Audacht Morainn. (Dublin: The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1976) Koch, John T., editor, in collaboration with John Carey. The Celtic Heroic Age: Literary Sources for Ancient Celtic Europe and Early Ireland & Wales, (Oakville, CT and Aberystwyth: Celtic Studies Publications, 2001) ---, editor. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, vol. 1-5. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2006) Mallory, J.P. In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archeology and Myth (London: Thames & Hudson, 1989) Maurer, Walter H, translator. Pinnacles of India’s Past: Selections from the Rgveda. (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1986) O’Flaherty, Wendy Doniger, translator. The Rig Veda: An Anthology (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1981) Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí, The Sacred Isle: Belief and Religion in Pre-Christian Ireland. (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999) Puhvel, Jaan. Comparative Mythology. (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1987) Rees, Alwyn and Brinley Reed, Celtic Heritage: Ancient Tradition in Ireland and Wales. (London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd., 1961, re-printed 1998) Taggar-Cohen, Ada. Hittite Priesthood. (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag WINTER, GmbH, 2006) Wait, Gerald A., “Burial and the Otherworld” in Green, Miranda J., editor. The Celtic World. (London and New York: Routledge, 1995) Watkins, Calvert, editor. The American Heritage Dictionary of Into-European Roots. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000) 6