Ideas Have Consequences - Alabama Policy Institute

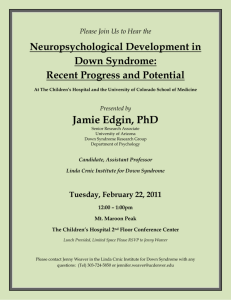

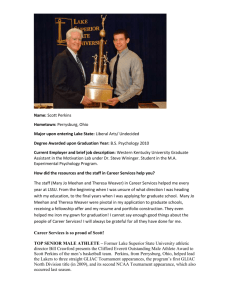

advertisement