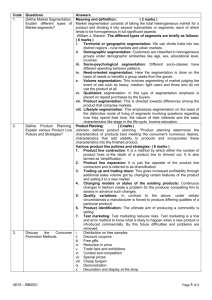

Market Segmentation Strategy, Competitive Advantage

advertisement