Spring 2012 - Sandwich Glass Museum

advertisement

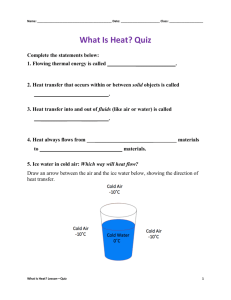

THE ACORN Journal of The Sandwich Glass Museum The Boston Glass Manufactory spring 2012 The Acorn • Spring 2012 1 Above: Glassworkers engaged in gathering, blowing, reheating, and otherwise manipulating cylinders for windowpanes. The illustration was included in the document collection of Frederick T. Irwin, who wrote The Story of Sandwich Glass. Author’s collection. Right: To make a table of crown glass, a glassblower takes a large amount of glass on his blowpipe, blows a large sphere, and flattens it. Then an assistant attaches a pontil to the center of the flattened side. The glass is detached from the blowpipe, leaving an opening about 2” in diameter. The pontil is rotated until centrifugal force causes the glass to fly open, resulting in a flat disk. This illustration is from Rev. Dionysius Lardner’s The Cabinet Cyclopedia: Useful Arts, published in London, England, in 1832. It depicts the maker twirling the disk to widen it, which creates a flat table 50” or 60” in diameter. The table is detached from the pontil and, after annealing, is scored for cutting into panes. Sandwich Public Library. Cover: Trade card c. 1885, uncirculated, of an alchemist recording the results of his experiments using an assortment of laboratory objects. Author’s collection. 2 The Acorn • Spring 2012 The Boston Glass Manufactory by Joan E. Kaiser T he Boston Glass Manufactory was a June 17, 1809, reorganization of the Boston Crown Glass Company to which the Commonwealth of Massachusetts General Court had granted the privilege of manufacturing crown window glass and bottles in the town of Boston, Massachusetts, on July 6, 1787.1 The capital investment of the new corporation was $250,000. Interestingly, of the eleven original partners, Boston-born Robert Hewes (1751–1830), is most often associated with the firm’s founding, although his direct involvement was only for a limited period of time. It was his second of three short-term ventures in the window glass business. Known as a colorful gentleman, Hewes’s early years included managing the family slaughter house as well as the closely related making of candles and soap, the manufacture of starch and liniment, and such occupations as fencing, surgery, and bone setting.2 His first glassmaking venture that glass scholars are aware of took place in Temple, New Hampshire, where in 1780 he erected a factory for the production of crown glass and chemical ware. He named it the New-England GlassWorks. Production of samples had barely gotten under way when the factory burned down. Hewes rebuilt it, but the harsh New Hampshire weather caused frost to destroy the furnaces. After major repairs that did not hold, some glass was made in the fall of 1781, but, by the end of the year, Hewes gave up. However, believing that the fast-growing New World’s most pressing need was for window glass, he returned to Boston’s more favorable climate and independently petitioned the Commonwealth of Massachusetts General Court, due to assemble in January 1782, for financial assistance and a fourteen-year patent to erect a glass works on Pleasant Street in Boston. The General Court granted Hewes a seven-year patent on March 1, 1783, but he failed to establish the Pleasant Street works. On July 6, 1787, his petition was rescinded in favor of that granted to the newly established Boston Crown Glass Company of which he was an associate. Hewes’s affiliation with the new firm was brief; his name disappears from company documents by October of that year, long before mass production got under way.3 In 1788 he became a partner and the first superintendent of the East-Hartford Glass-Works, usually called the Pitkin Glassworks, of East Hartford, later Manchester, Connecticut. The Pitkin firm was formed in 1783, but its production of bottles and crown window glass did not begin until Hewes’s arrival five years later. His connection was severed before October 1789, and, as far as is known, he disappeared from the glass industry scene.4 The eleven associates who founded the Boston Crown Glass Company appointed a committee of two to locate an appropriate lot on which to erect a glasshouse. They selected a property on Essex Street between Short Street and Peck Lane overlooking South Cove, a bay that separated Boston from South Boston. A brick, pyramidal shell of a glasshouse was erected in 1788. It had no chimney, only a ventilator. By way of congratulations, John Amelung of the New Bremen Glassmanufactory (sic) near Frederick, Maryland, sent an engraved tumbler dated January 23, 1789, to the Boston company’s directors. By November 1790 glassmaker Frederick E. A. Kupfer had been hired to construct a six-pot furnace, an annealing oven, and six wood-drying ovens. However, glassworkers hired by Kupfer determined that the 1788 glasshouse itself was unsuitable for making crown glass. The brick shell was taken down and construction began anew. A 100’ by 60’ wooden house with a brick chimney was erected in its place.5 Support buildings included a store. Glassmaking in the Essex Street works finally began on November 11, 1793, under the superintendence of one Samuel Gridley. The foreman was Frederick Kupfer’s son, Charles F. Kupfer, who also served as clerk. The first employees were German blowers, some of whom had worked in Hewes’s Temple works and others obtained from a factory in Baden-Baden, Germany. The earliest The Acorn • Spring 2012 3 glass was not well made, but after eventual success it was described as “good and brilliant glass, of a light bluish white color and quite thick.” According to a 1795 Boston advertisement, the panes were sized from 6” x 8” to 19” by 13”. With thirty-two pounds of melted glass taken on a blowpipe, a circular, flat disk of finished glass, termed a table, could measure as large as 60” in diameter. Under a patent granted on June 15, 1793, the firm also was required to produce hollowware such as bottles and carboys. However, if these objects were made this early in the firm’s history, they were not advertised and cannot be identified today.6 With cities springing up all over America and the need for window glass increasing, two directors of the Boston Crown Glass Company were sent to Middlesex Village, later Chelmsford, Massachusetts, to erect a factory for making cylinder window glass. Unlike crown glass, the less-expensive cylinder glass was made by blowing large tubes that were cut open and flattened by annealing. The Chelmsford works opened in 1802. The main building was 124’ long by 62’ wide, with two furnaces, three flattening ovens, and six wood-drying ovens.7 Above: Crown glass window, 18th Century American, set with windowpanes commonly called “bull-eyes” that feature pontil scars in the center of each pane. It will be displayed in the special exhibition, Pressing Business. Gift of Byron U. Richards in memory of Ross W. Richards. As stated previously, on June 17, 1809, the Boston Crown Glass Company reorganized as the Boston Glass Manufactory, the name by which it would be known throughout its lifetime. With plans for continued expansion, on March 15, 1811, the company purchased from the South Boston Association a lot of upland in South Boston.8 It was located between First and Second Streets and bounded on the southeast by B Street.9 A building housing South Boston’s first glass furnace, where crown glass would be blown, was erected on the westernmost section of the lot. A house with a six-pot flint glass furnace was built in the center, just east of and parallel to the crown glasshouse. In anticipation of a successful venture, this time the company looked to England for competent blowers. A search by Charles Kupfer produced skilled workmen, including an expert batch mixer and blower of flint glass, Thomas H. Cains (1779–1865), who had apprenticed in Bristol, England, at the Phoenix Glass Works. He was working independently at the time of their meeting. Kupfer hired Cains as foreman of the flint works with the understanding that he would produce tableware and an assortment of apothecary furniture and chemical ware.10 The Englishmen arrived, ready to begin a new life in a new country. However, they had little to do. Their endeavor was interrupted by a war between the United States and England, declared on June 18, 1812. As had happened during an American Revolutionary War battle in 1776, two high hills in South Boston, known as Dorchester Heights, were fortified for several regiments 4 The Acorn • Spring 2012 of the Massachusetts militia. A watch was stationed on the heights because British warships were in sight and at times came into Boston Harbor, which was guarded by U.S. troops. To the relief of less than brave Massachusetts soldiers, who had been enlisted for only thirty days, there was no battle.11 However, soldiers overrunning and pillaging the land and the inability of industry to obtain raw materials caused the South Boston works to close temporarily. Finally both furnaces were producing by the end of 1812. The Boston Glass Manufactory advertisement placed by Charles Kupfer in the December 16, 1812, newspaper Columbian Centinel is believed to be the earliest that includes ware from foreman Cains’s flint glass furnace. BOSTON WINDOW GLASS AND GLASSWARE— The Proprietors of the Boston Glass Manufactory, inform the public, that they have on hand, a quantity of Boston and Chelmsford GLASS, of various sizes—among which, are 6 by 8, 7 by 9, 10 by 8, and other sizes as high as 18 by 24. Irregular sizes and Fan lights are cut in the shortest notice. Also, Entry and Gate lamps; Chimneys and other Lamp Tubes, of different shapes. Likewise Tumblers and Phials; Retorts; Apothecary’s Furniture and Medicine Bottles; Chymists and Electrical Apparatus;— together with sundry other glassware. Orders executed at the shortest notice on application to C. F. Kupfer, at the Boston Glass House, Essex St. Another advertisement dated April 20, 1815, and published in subsequent issues of the Columbian Centinel and Boston Gazette illustrates a table of crown glass and blowers working at a crown glass furnace. It lists a variety of items available from the Boston, Chelmsford, and South Boston works.12 Yet, despite the glowing claim that “the Glass Ware is pronounced by judges, not to be inferior in quality and workmanship to any imported,” during the company’s formative years the flint ware in particular was far from the quality that foreman Cains’s reputation later would be known for. By the time of this advertisement until the end of 1818 the firm’s agency was under the management of Edward A. Pearson. This gentleman dedicated many hours writing to current and potential customers, and other company agencies that were established in major cities. It is our good fortune that his clerk hand copied those letters into a letter book now held by the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library in Winterthur, Delaware.13 (The letter book firmly documents the company’s activities. It clarifies written histories that are based on the somewhat inaccurate memories related in 1880 by Thomas Cains’s sixty-five-year-old son, William.14) Many letters were in the form of apology for inefficiency because, for example, an object that should be in stock was not, and therefore would not be available for some time, particularly if a certain color was ordered. This was especially true of the flint glass works because only three of Cains’s six pots were used for working glass. The other three were used for drying wood. Certainly production was derailed when during a shakeup three key flint glass employees—William Emmett, George Flowers, and John or Richard Fisher—walked away and leased the Boston Porcelain and Glass Company’s factory in East Cambridge, Massachusetts. There was no production at all when the fire was put out for more than three weeks in September and October 1816 to rebuild the single furnace. And there was not much hope for adding a second furnace as industry limped along during the years of desperate economy that followed the War of 1812. Pearson’s letter book introduces the glass scholar to a segment of the glass industry that often has been overlooked. Correspondence of December 5, 1816, to William Wardlaw and Company of Richmond, Virginia, is enlightening in view of a reference to “Henry’s Chemistry”: Since last addressing you, particular attention has been paid to y’e manufacture of Apoth. & chem. Apparatus of every description, all ye articles referd to in the plates to Henry’s Chemistry are made, & we are now executing Orders for several Public Institutions. Left: This windowpane was the center section of a table of crown glass, commonly described as “bull’s eye” because it incorporates a scar from a pontil. As seen in this end view, the thickness varies. All panes cut from a table vary in thickness, even those cut from outer sections. To meet such wavy undulations, a glazier, when setting them in window frames, was required to carve the wooden mullions that separate them. Private collection. The Acorn • Spring 2012 5 “Henry’s Chemistry,” or, formally, The Elements of Experimental Chemistry was written by William Henry (1774–1836), an English chemist and the discoverer of Henry’s Law. First published in London, England, as two volumes in 1806, it became a standard work. Ten plates of scaled line drawings included in the 1814 London edition allowed apothecaries, chemists, perfumers, and college professors to set up a laboratory with apparatus made to their specifications. The first American edition, published in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1819, includes plates from the London editions. They allow us to see exactly what is meant by “apothecary and chemical apparatus.”15 Four of Pearson’s letters fill a gap in the saga of Philadelphia’s Thomas W. Dyott (1777–1861), a purveyor of medicine for venereal complaints and patent medicines that he sold by the brand name Dr. Robertson’s Family Medicines.16 Dyott opened a medical practice in 1805. By 1809 he added a dubious medical degree to his name and owned a private mold for blowing square flint glass bottles. Soon he was in the flint glass business, selling bottles to other druggists and “doctors” like himself. In 1814 he had commissioned fourteen agents in the greater Albany, New York, area alone. At that time one of his bottle sources was the Kensington Glass Works in Kensington, near Philadelphia, which ceased production by 1815. With the Kensington works out of business, Dyott turned to two New Jersey factories, the Olive Glass Works and the Gloucester Glass Works, and became an agent for these concerns. He also sent Pearson orders to be filled by the South Boston Flint Glass Works. Above: Plate I from the 1819 edition of The Elements of Experimental Chemistry, written by William Henry. The miscellaneous chemical ware includes a retort (Fig. 1a), a tabulated receiver with and without stopper (Fig. 1b), an alembic (Fig. 2), roundbottomed flasks (Figs. 4 and 5), and a retort with stopper (Fig. 13a). The scale at the bottom represents 24”. Richard A. Paselk, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California. Opposite: Blown-molded Turlington bottles. Englishman Robert Turlington patented his medicinal, twenty-seven-ingredient “Balsam of Life” in 1744. His original bottles were curved, but he later angled their form to prevent counterfeiters from buying them back and filling them with generic versions of his cure-all. Turlington’s plan failed. Over the next 150 years, numerous glass companies included more than ten variants of these hard-edged bottles, which were sold empty to the trade. The lip of the South Boston Flint Glass Works’s first variant may be flared rather than welted to the outside like the bottles shown here. Bottle on left: James Megura Collection; bottle on right: Joan E. Kaiser. 6 The Acorn • Spring 2012 Pearson communicated with Dyott four times in 1817. On April 25 Dyott was informed “The mould for the Patent bottles is now made & in a short time will be forwarded with the remaining articles not now sent.” A letter of May 24 mentions a total of six cases of glassware as well as species mouths and essence vials, and that of July 30 accompanied an invoice for two more cases. On August 15 Pearson apologized for an order “which in the hurry of bus[iness] was overlook’d.” One month later the Philadelphia Press of September 17 published a notice of Dyott’s stock on hand. Certainly a portion of this inventory had come from South Boston. No further correspondence appears in the Pearson letter book. Dyott bought into and eventually owned a second Kensington Glass Works built on a lot near the earlier Kensington works that had closed. It is interesting to study how closely Dr. Dyott’s Prices Current: Glass Ware of the Philadelphia and Kensington Vial and Bottle Factories17 of the 1820s follows the format of the 1819 Prices Current of South Boston Flint Glass Ware.18 As indicated previously, Thomas Cains was a man of high standards, but as foreman he had little control over the direction imposed by those who had financial interest in the business. Finally, in January 1818, after five years of overseeing the making of substandard objects, he bought into the corporation. Changes were immediate. The South Boston Flint Glass Works would compete in the market by blowing, as well as pressing, objects with improved design, weight, and form. To offset the increased cost of production, common bottles would be made of non-flint glass that was not decolorized, termed green glass. The restructuring had little effect on an already eroding morale. The wooden building that surrounded the Boston Glass Manufactory’s single crown glass furnace blew down in a gale in September 1818 and was rebuilt out of brick, adding expense and causing delays in shipping windowpanes. There was infighting among upperechelon employees of all three factories. Research of glass scholar Lura Woodside Watkins determined that the person responsible for the lack of harmony was John S. Foster (–1834). He was a window glassmaker at the Chelmsford factory who was working his way up in Boston Glass Manufactory management. For the long term, he was inept in both capacities.19 Yet as treasurer and assistant clerk, he soon controlled Edward Pearson’s accounts receivable. Apparently preparing to resign, Pearson instructed his customers to remit the balance of their accounts before February 1, 1819, and pay directly to Foster. Pearson’s letter book ends here. Thomas Cains was considered moderately successful at the flint works, but in 1822 continual mismanagement of the parent concern caused him to look elsewhere for employment. After turning down several job opportunities, he built his own factory on property that he owned on the eastern side of B Street. First called Cains’ Glass House, it would be family operated until it shut down in 1870. Meanwhile, at the Boston Glass Manufactory, conflicts with Foster led to Charles Kupfer’s eventual resignation. The year 1824 saw reorganization again. The South Boston property remained under the ownership of the Boston-based concern, but its management was split into separate ventures. One group that included Foster incorporated as the South Boston Crown Glass Company on February 4, 1824, to continue making windowpanes at the crown glass furnace. On February 22, 1825, a second group incorporated under the firm name South Boston Flint Glass Works, intending to produce flint glass by leasing from the Boston Glass Manufactory the glasshouse vacated by Cains. Above left: Blown-molded liquid opodeldoc Boston prescription bottle. The bottle’s cylindrical form is identified as Boston by the glass bottle industry. Opodeldoc, with emphasis on the third syllable, was a soapy liniment made of a solution of soap, distilled spirits, camphor, and essential oils. The Boston Glass Manufactory’s agent Edward A. Pearson invoiced such bottles at $8.00 per gross on March 14, 1816. Such bottles were made of flint glass until 1818, when Thomas H. Cains bought into the parent corporation and changed company policy. Author’s collection. Above right: Twelve-ribbed and sixteen-ribbed objects are documented to the hand of Thomas H. Cains. This peacock green pungent was blown in a mold that had sixteen vertical ribs. Twisting it after removal from the mold produced the diagonal configuration. It is of the form that in 1877 Cains’s son, William, showed to a Dorchester newspaper editor, who described it as “a blue smelling bottle, of the twisted comical (sic) pattern formerly so much in vogue that came into existence over sixty years ago.” “Smelling or Pungents, moulded and twisted” are itemized in the 1819 Prices Current of South Boston Flint Glass Ware. Author’s collection. The Acorn • Spring 2012 7 Both groups had to know that their futures were tenuous. The Boston Glass Manufactory borrowed $15,000 on July 7, 1825, by using its two South Boston works as collateral.20 The mortgage would have been satisfied in 1829, but the parent corporation together with its Chelmsford and South Boston subsidiaries declared bankruptcy in 1827. The failure ended Foster’s career in Boston. He moved to Burlington, Vermont, to establish a cylinder glassworks on the shore of Lake Champlain.21 Most of the Boston Glass Manufactory’s South Boston property reverted back to the South Boston Association. On May 26, 1827, the real and personal property connected with the glassmaking facility was conveyed by bankruptcy proceedings to assignees, who published the following notice, dated June 11, 1827, in the Boston Commercial Gazette: Boston and South Boston Crown Glass and Chelmsford Cylinder Glass for sale. A quantity of Glass of all the sizes and descriptions usually manufactured at the Boston, South Boston and Chelmsford works, also a quantity of Materials and Utensils. Inquire at the late Counting Room of the Boston Glass Manufactory, Essex-street. The making of Glass at the above mentioned works has been discontinued. How much inventory was sold is open to conjecture. It was rumored that unsalable crown glass worth $150,000, termed rusty by window glass industrialists, was left in Boston at the Essex Street factory. It was destroyed by fire on February 16, 1829. Under different ownership, the Chelmsford factory continued production until 1840. Top left: Free-blown whale oil lamp with interior air trap, threethread decorated standard, and pressed rose foot. The South Boston Flint Glass Works first listed stand lamps in 1819, although pressed glass was introduced into the United States in 1817. The horizontal ring around the font was made by incising a deep groove into the exterior surface and smoothing the glass over the groove. Air trapped in the groove, when viewed from the exterior, appears as two silvery rings. This was one of several motifs commonly employed under Cains’s supervision. A three-thread hoop decorates the standard. The form of the standard is unique to lamps manufactured in South Boston. The standard was free blown and then rotated in a wooden block that was hollowed to this configuration. Art and Kathy Green Collection. Left: South Boston’s earliest stand lamps were constructed by adhering a rudimentary peg to the bottom of the font by means of a disk of glass, called a wafer, and thrusting the peg through a larger wafer that attached the whole to a blown hollow standard. The rudimentary peg of the font unit is clearly visible where it protrudes into the standard. It is not found on Sandwich Glass Manufactory and Boston & Sandwich Glass Company lamps, first made in 1825. Note the distinctive form of the standard. Private collection. 8 The Acorn • Spring 2012 The remaining inventory of stock produced in the flint glasshouse was purchased by the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company. That company had been founded only two years earlier as the Sandwich Glass Manufactory with a warehouse in Boston and one eight-pot furnace in Sandwich, Massachusetts. The glassworks lot was subdivided into two parcels, the westernmost one on which the crown glass furnace stood and the easternmost one on B Street on which the flint glass furnace stood. On August 13, 1828, the easternmost parcel was sold to Edward A. Pearson, former agent of the Boston Glass Manufactory now identified as a broker. He continued production primarily by pressing cup plates, and to better compete in this market he soon constructed a small two-pot furnace in a converted outbuilding. On March 6, 1830, he and one Levi Farwell incorporated the business as the Boston Flint Glass Company. The firm is listed in the 1830 Boston directory; however, by November the works was offered for sale to the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company and East Cambridge’s New England Glass Company. Left: Free-blown whale oil lamp with pressed square Lacy base. Without question the base with its Lacy pattern beneath was also produced by the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company. Yet the beautifully shaped font is unlike fonts attributed to the Sandwich works. It does, however, mimic the form of South Boston standards. The author believes that the lamp was made in South Boston and that the mold in which the base was pressed was one of those acquired later by the Sandwich firm. Art and Kathy Green Collection. The Boston & Sandwich Glass Company’s directors appointed a committee to consider Pearson and Farwell’s proposal. It recommended the purchase of the stock, tools, and materials. Another committee conferred with a New England Glass Company committee to consider the real estate. For reasons unknown to the author, that transaction did not occur. In 1833 the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company built a ten-pot furnace in Sandwich, which, with a six-pot furnace built in 1829, brought its total number of furnaces there to three. Above: Research indicates that the square Lacy lamp base, shown here on a Sandwich lamp, was pressed in a mold that the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company purchased from the Boston Glass Manufactory’s South Boston Flint Glass Works in 1827, or in 1830 from Edward A. Pearson and Levi Farwell’s Boston Flint Glass Company. Sandwich Glass Museum, Sandwich Historical Society. Left: The author believes that this square scrolled standard and paw foot (lion head) lamp base is another that was pressed in a mold that the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company purchased from the South Boston Flint Glass Works in 1827, or in 1830 from Edward A. Pearson and Levi Farwell’s Boston Flint Glass Company. The base is common to Sandwich, but is found on an intricately constructed, 14¾” high candlestick with South Boston characteristics that is in the Toledo Museum of Art in Toledo, Ohio. It is pictured in Kenneth M. Wilson’s American Glass 1760–1930 I, page 343, plate 433. The head of an animal thought to be a lion is molded between the upper ends of the S-scrolls. Sandwich Glass Museum, Sandwich Historical Society. The Acorn • Spring 2012 9 Right: The domed foot of this labor-intensive, free-blown candlestick mimics the form of a sugar cover that descended in the Cains family. A gaffer with a keen sense of design and proportion made it. The nozzle’s galleried rim suggests that it was furnished with a pewter socket into which a candle was inserted. Low and high candlesticks are itemized in the 1818 Prices Current. The 1819 Prices Current lists “low tale” and “high best” candlesticks. Private collection. Below: Profusely illustrated Boston Glass Manufactory billheads were used by the agencies of Edward A. Pearson in 1815 and of Joseph Wing and Stephen Sumner in 1821. This blown-molded diamond-patterned salt is one of twelve objects depicted with two tables of crown glass and a box of cylinder windowpanes against a background of the three glassworks. James Poore Antiques. The Boston & Sandwich Glass Company and the New England Glass Company’s joint involvement in the South Boston works continued, however, as documented by a deed finalizing its sale in 1833. When it was bought by George C. Shattuck on June 8 of that year, the sale was subject “to a lease from said Company of the same premises for five years yet unexpired upon the conditions therein contained to the Boston & Sandwich & New England Glass Companies.”22 Exactly when the five-year lease was formalized, when it expired, and whether it was renewed cannot be determined by the author. Presumably the agreement was signed in 1831, around the time that the Sandwich concern voted to purchase the stock, tools, and materials. (To date the author has identified two lamp feet that were pressed in molds that most likely were transferred from the South Boston facility to the Sandwich works.) Over the next several years, a financial depression that affected industry worldwide swept across the United States. It led to the Panic of 1837 that virtually destroyed the market for glass. Any attempt by a flint glass firm, large or small, that may have occupied Shattuck’s property after the lessees vacated would have been poorly rewarded. Some activity was noted there in 1845, perhaps in preparation for leasing it to Patrick F. Slane (c.1817–1888), who ran a flint glassworks in East Cambridge, just a stone’s throw west of the New England Glass Company’s factory. He moved his entire American Glass Manufactory to South Boston in 1847. Here he was fairly successful in the low-end and middle market until 1857, when he relocated again, this time to New York. His corporation was the last to manufacture glass on the site.23 On April 29, 1829, the crown glass parcel was sold to Edmund H. Monroe (1780–1865), a Boston broker of real estate and securities as well as an incorporator of the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company and three glass companies with furnaces in East Cambridge. On October 28, 1830, Monroe sold it to Charles, David, and John Henshaw, who converted it into a distilling and refining facility. When the depression hit, Monroe found himself relinquishing his interests in all of his South Boston real estate. After several transfers of ownership, some of his lots became the property of the Boston Chemical Laboratory. The laboratory and the Henshaw distillery properties evolved into the massive Downer Kerosene Works. 10 The Acorn • Spring 2012 AFTERWORD It has been noted that the author’s history of the South Boston glass industry “left no stone unturned.” There are two stones that need upending. The first involves the elusive adventures of one William Eayres, whose career in the business spanned less than a decade.24 In the early 1830s some of the former Boston Glass Manufactory’s lots in the vicinity of Second Street and A Street became the site of numerous short-lived bottle houses and flint glasshouses. Eayres managed a flint works there in 1834 and 1835. Previous to that, in 1828 and 1829 he lived on Broadway in South Boston and was employed as the agent of an unidentified, but seemingly local glass company. He then moved to Providence, Rhode Island, where in January 1831 with nine others he incorporated the short-lived Providence Flint Glass Company. He served as its agent until it shut down in 1833. By 1834 he returned to a South Boston residence on Third Street. He is listed as a glassmaker in the Boston directory of 1835, after which he is no longer found as a South Boston resident or businessman. As Eayres is not a common name, William probably was related to one Ebenezer Eayres, who on October 22, 1788, fell from scaffolding during construction of the chimneyless factory on Essex Street.25 The author requests the reader’s assistance in determining the firm for which William Eayres served as agent in the late 1820s. Nathaniel Staniford, or Stanniford, is another figure who fades in and out of history.26 The 1827 Boston directory lists him as a glasshouse manager on Second Street. The time of his arrival in South Boston is not known to the author because South Boston residents were not included in the directory before that year. He may have been a superintendent under Thomas Cains at Cains’ Glass House. As far as is known, Cains’s was the only working flint house at the time, unless Edward Pearson had reopened the South Boston Flint Glass Works earlier than current research suggests. Boston & Sandwich Glass Company correspondence connects him to a flint rather than a bottle or window glass factory. A letter dated September 17, 1827, notes that he had five hundred tubes, or burners for whale oil lamps, made. Another dated October 31, 1827, reveals that “Stanniford makes a Cylinder Night Lamp broad at Top.” During his tenure in South Boston, a magnificent free-blown mug was created that he presented to Captain Ebenezer Goddard, Jr. (1779–1838), whose life history is also elusive. Information on Nathaniel Stanniford would be greatly appreciated. Notes 1. Joan E. Kaiser, The Glass Industry in South Boston (Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2009), 7. 2. Kenneth M. Wilson, New England Glass & Glassmaking (New York, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1972), 51–58. 3. Ibid., 57, 59. 4. Helen McKearin and Kenneth M. Wilson, American Bottles & Flasks and Their Ancestry (New York, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1978), 54–58. 5. Kaiser, The Glass Industry in South Boston, 233. 6. Wilson, New England Glass & Glassmaking, 79–82. 7. Ibid., 83. 8. Suffolk County (Massachusetts) Registry of Deeds (henceforth Suffolk Registry), book 235, pages 241–243. 9. A locator map illustrating the layout of the Boston Glass Manufactory’s South Boston properties is found in Kaiser, The Glass Industry in South Boston, 8. 10.Ibid., 7. Further information is found in chapters 2, 3, and 4. 11.Thomas C. Simonds, History of South Boston: Formerly Dorchester Neck, Now Ward XII of the City of Boston (Boston, Massachusetts: David Clapp, 1857; Reprinted by Higginson Book Co., Salem, Massachusetts, n.d.), 105–106. 12.Wilson, New England Glass & Glassmaking, 202. 13.Edward A. Pearson’s letter book in the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library is in the Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, no. 82x57. It was brought to the author’s attention by glass scholar and friend, Maynard E. Steiner. 14.Kaiser, The Glass Industry in South Boston, 235, note 7. 15.Ibid., 15–19. 16.Helen McKearin, Bottles, Flasks and Dr. Dyott (New York, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1970). 17.Ibid., 38. 18.Leith Smith, Barbara Donohue, and Martin Dudek, Emergency Archaeological Data Recovery of the South Boston Flint Glass Works and the American Glass Company (Formerly Reported as Crown Glass Works); Contingency Plan Implementation; Contos Property, Parcel 60-CS-1; Central Artery/Tunnel Project; Boston, Massachusetts, vol. 2 (Littleton, Massachusetts: Timelines, Inc.; for Boston, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Highway Department, 2000), Appendix E. This publication is a detailed report of an archeological dig that was conducted on the site of the South Boston Flint Glass Works in 1997 (Kaiser, The Glass Industry in South Boston, 72–74). The 1818 and 1819 Prices Current are courtesy of Kenneth M. Wilson, whom Smith consulted. 19.Lura Woodside Watkins, “The Boston Crown Glass Company,” Magazine Antiques 37, no. 6 (June 1940), 291. 20.Suffolk Registry, book 301, page 230. 21.Kaiser, The Glass Industry in South Boston, 234, note 21. 22.Suffolk Registry, book 369, pages 212–213. 23.Kaiser, The Glass Industry in South Boston, chapter 5. 24.Ibid., 1, 133. 25.Wilson, New England Glass & Glassmaking, 79. 26.Kaiser, The Glass Industry in South Boston, 27–28, 30–31. Back cover: Plate II from the 1819 edition of The Elements of Experimental Chemistry, written by William Henry. The miscellaneous chemical ware includes a funnel with trap termed safety funnel (Fig. 26a), a precipitating jar (Fig. 26f), and a burner (beneath Fig. 27a). An object with an extra neck, as shown in Fig.17a, was termed tabulated. The scale at the bottom represents 24”. Richard A. Paselk, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California. The Acorn • Spring 2012 11 SANDWICH GLASS MUSEUM • SANDWICH HISTORICAL SOCIETY 129 Main Street, Sandwich, MA 02563 • 508.888.0251 • www.sandwichglassmuseum.org 12 The Acorn • Spring 2012