Women in Shakespeare lecture notes

advertisement

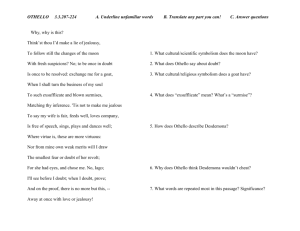

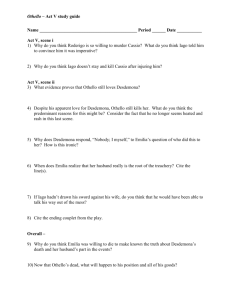

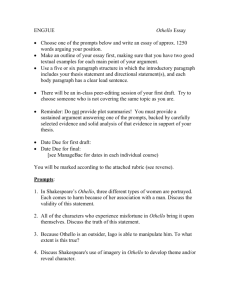

1 Women in Shakespeare. Slide 1: Welcome to this lecture on Women in Shakespeare. I am not a lecturer, by any means, and owe much of this lecture to the lovely Dr Emma Smith at Oxford University. I had the pleasure of seeing her lecture in 2012, and so I am BOWDLERISING HER WORK. Thomas Bowdler in 1818, published “The Family Shakespeare”– printed his versions of Shakespeare’s plays – the arrogance of making someone else’s work your own. For the main of the following, I’ll be referring to Othello and The Taming of the Shrew. Are there any other texts which you are studying – and I can try to make some intelligent commentary on that text – IF I know it!! Slide 2: At the end of the 1500s, there was a general concern among men, women, children and servants in terms of the social roles they should assume in the radically changing society, following the Reformation and in the Renaissance. Catholicism (the main religion before Henry VIIth established the Church of England in order to be able to divorce Katherine of Aragon) was very clear on topics such as sex – for procreation only – priests are sexless virgins, and this was the highest social order. For those who had to have sex, they must marry and face the consequences of this – all those awful children; marriage is the second best choice. Protestantism, however, is for marriage, for having children, encouraging the development of the family. As a result, there was a need for guidance and rules – how do people live as families? What roles must the different elements of the family play? Slide 3: So, one of the places to look is the Bible. Often, the Bible will give us much inspiration for Literature. Here, we see the basis for many of the Conduct Logs which we find as instructions for the women and families of that time – I’ll talk more about these in a minute. These quotations come from the Old Testament, which contains much of the teaching for the church, and the foundations of many of our social rules. Read text – note the word “submit”. This is reflected in the marriage ceremony – that the woman must “love, honour and obey”, which has now been replaced with “cherish”. There is a sense of the patriarchal will within the church, led by the monarch. The second quotation focusses on the behaviour of women – and the attitudes expressed here continue to this day. Slide 4: Conduct Logs were written to teach families how to behave. We assume much about the behaviour of women in the Elizabethan era, based on the evidence we find in Conduct Logs, which give advice such as: “…silence is the best ornament of a woman and therefore the law was given to the man, rather the(n) to the woman to shew that hee should bee the teacher, and she the hearer.” (Cleaver) “Nature hath placed an eminencie in the male over the female: so as where they are linked together in one yoake, it is given by nature that he should governe, she obey.” (Gouge) The Conduct Logs show us some of the ways that problems were dealt with, but often the quotations are taken out of context, and just to prove a point. 2 Slide 5: Some other quotations are: “there shal be in wedlocke a certain sweet and pleasant conversation, without the which it is no marriage, but a prison, a hatred and a perpetuall torment of the mind” (Cleaver) “of all degrees wherein there is any difference betwixt person and person, there is the least disparitie betwixt man and wife.” (Gouge) i.e. class is the greater differentiator. These give evidence of the companionate marriage, where couples aim for a happier balance. We see these equal relationships at the start of Macbeth where Macbeth refers to his wife as his “equal partner of greatness” and Othello, where Desdemona is Othello’s “soul’s joy”. Slide 6: Obviously, there is still evidence of the Scold’s Bridle and a shrew’s fiddle – used at the recent RSC production of The Taming of the Shrew. Katherina is dragged through the streets, mocked by the society which disapproves of her outrageous behaviour. She is the original UNRULY WOMAN - I’ll come back to this later. The legal system did allow for injustices against women, but these were mainly lower class, solitary folk who had no protection from those with grudges against them. This is NOT the norm. Slide 7: Very often, there is evidence of people in society being told how to behave e.g. wearing seatbelts, not smoking from the NHS. When the literature is in abundance, the people tend not to be complying. It is only once the law has full compliance that the campaigns can stop. If you look at the slide here, you can see that the older fashioned campaigns have ceased to exist because people now comply with the advice given. The same can be assumed about Conduct Logs. They prescribe, rather than describe. Slide 8: Class was of higher concern to the Elizabethans than gender, and Shakespeare was a conservative as far as class is concerned – much of the humour in The Taming of the Shrew comes from servants pretending to play masters, but they all happily return to their natural state; Iago (in Othello) is a servant, an ensign, who tries to improve his position, and is damned for this. Shakespeare’s audience are much more concerned by class than gender; he ensures that those who pretend to be higher class must return to their servant status, and those who try to claw their way up are punished. Slide 9: Let’s get back to issue of how women are represented. Do we expect entertainment or even higher culture to hold a mirror up to our lives? Perhaps at times, but very often, our impulse is to be taken outside of ourselves, either for comedy and relief, or to try to imagine our own responses in a certain set of circumstances. Can we really expect the theatre to give us a truthful representation of women? After all, Hollywood Rom-Coms do not reflect our lives truthfully. Jennifer Aniston? Meryl Streep softening Margaret Thatcher to a more palatable form? Drama is not a mirror up to life – it would be inanely boring if it were, and Shakespeare is not a realist. We would never compare the endless live feed on Big Brother to the edited highlights, people want the boring bits edited out. 3 Is Shakespeare representing women as they really are at that time? Perhaps – but not all of the time. Slide 10: In general, we can look at Shakespeare’s plays in their two categories: Comedies and Tragedies. Comic heroines tend to be commanding, authoritative and controlling. They often take on the garb of men in order to exert their world view e.g. Rosalind in “As You Like It” and Viola in “Twelfth Night”. Tragic females tend towards the passive, have less to say and die early on e.g. Ophelia gives herself up and Lady Macbeth burns herself out. As she fades away, Macbeth gets better and better at murder. She begins as Machiavellian, astounding, shocking, but loses her all of her power. There is a commonality in each form, which you may recognise and apply to your texts. Comedies vs Tragedies: Movement towards marriage and social cohesion, tragedies towards isolation, breakdown of society and death. Tendency to dialogue, whereas Tragedies tend towards soliloquy – Hamlet, Iago. Transfer to location is full of possibility. Woodland locations in As You Like It and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Petruchio’s house in Taming? We’ll get into that later. In Tragedies, the transfer to other locations intensifies old problems e.g. in Othello, moving to Cyprus leads to more jealousy and violence. Puns tend towards sexual innuendo and fecundity, whereas Tragic puns tend towards nihilism, death and sex – the impossibility of a true connection e.g. Iago’s fascination with sex. FEMALE CHARACTERS PROMINENT AND ACTIVE vs MALE CHARACTERS PROMINENT AND ACTIVE. Multiplication vs Division Slide 11: In most Comedies, women are given controlling roles, and in Tragedies, the men are given pivotal characters; there are exceptions, particularly Juliet and Desdemona., who I’ll focus on here. Juliet and Cleopatra are fairly equal to the men in the plays, and end up dying last. At the beginning of their relationship, Juliet has the upper hand with Romeo – she demands a promise of everlasting love (“Swear not on the inconstant moon!”), a plan to marry (“Wilt thou leave me so unsatisfied?”) But, by the end of the play, she has lost all of her power, and her only option is to die. Juliet starts as comic and dominant, and ends the play as the tragic female. If only she had a Sassy Gay Friend to sort her out – watch Sassy Gay Friend on Youtube – It would all be so much easier if Juliet just stepped out of the role that she is being forced into. There are loads more on there, folks. Enjoy! 4 Slide 12: Desdemona starts the play as a comic female – strong and brave, standing up to the men at court, particularly her father, who she rejects in favour of her Moorish husband, Othello: “My noble father, I do perceive here a divided duty: To you I am bound for life and education; My life and education both do learn me How to respect you; you are the lord of duty; I am hitherto your daughter: but here’s my husband, And so much duty as my mother show’d To you, preferring you before her father So much I challenge that I may profess Due the Moor my lord.” Desdemona is bringing the domestic into the world of men. Othello trusts her – they have the ideal of the time, the “Companionate Marriage”. However, once Desdemona insists that she go to Cyprus with Othello, she becomes the object in the tragedy. : And:”That I did love the Moor to live with him… …the rites for which I love him are bereft me…” The sexual nature of this comment reflects her more comic-prominent role at the start of the play. She is not passive at the start, nor diligent or obedient, but by the end of the play, she takes the blame for her death from Othello. Desdemona: O, falsely, falsely murder’d! Emilia: Alas, what cry is that? Othello: that! What? Emilia: Out, and alas! That was my lady’s voice. Help! Help, ho! Help! O lady, speak again! Sweet Desdemona! O sweet mistress, speak! Desdemona: A guiltless death I die. Emilia: O, who has done this deed? Desdemona: Nobody; I myself. Farewell Commend me to my kind lord: O, farewell. Desdemona has completely allowed herself to be part of Othello’s will and narrative. It is worth watching different endings of the scene on Youtube – sometimes she is passive in white, sometimes 5 fighting. The wife murderer is always uncomfortable to watch – particularly for the 16th century audience. They would see the scene with extreme pity and pathos, and their focus would have been the loss of Desdemona. She never argues about the handkerchief, and becomes submissive – why? Has she been battered, abused? Why doesn’t she fight back more vociferously? She argues her innocence: “I am a Christian”, but she never states her case to Othello like she did to the Duke and her father. Because of the inconsistencies in her character, she is often criticised by literary critics. In Shakespeare’s construction, Desdemona begins as a strong, comic character and is subsequently changed into a tragic one. For Othello, the play begins in comedy – with a comic villain, and it is Desdemona who drives the play forward – to Cyprus, where Iago can then be reincarnated as the Machiavellian monster he is – remember, he cannot justify his actions, and can’t locate the crux of his anger/unhappiness. Emilia, Iago’s wife, has comic characteristics – she speaks about men’s sexual appetites (“we are but food, and they stomachs”) in a comic way. Towards the end, she becomes more prominent/active, and seems to switch power with Desdemona. By this time, Shakespeare has written 10 comedies and only 2-3 tragedies, so he is more skilled in writing these comic, controlling women. Slide 13: In the Taming of the Shrew, it may be possible to view Katherina as beginning as tragic and ending as comic – at the start of the play, she has little to say and no-one will listen to her, but by the end of the play, she is centre-stage, holding all the women in thrall and telling them how to behave: the comic heroine. Look at the final speech of Katherina’s, explain the wedding, her recent elevation in status to “married woman”. Slide 14: Different readings of Katherina’s final speech. Focus on the importance of being able to look at texts in different ways, to interpret texts with the context in the back of our minds. Certainly, this second reading is more acceptable, whereas the Victorians loved the first reading. For many years, the play was just not approached, because of the difficulties of how this final speech. By 1610, women are allowed to come to the theatre, and have more influence. Are the plays prior to this to be seen as plays for men only, played by men or hermaphrodites? Men in the audience will certainly recognise the character of the unruly woman – the shrew. These women still entertain us with their refusal to fit into stereotypes – Ab Fab is a great example, as is Miranda. Elizabeth 1st never married, refusing to give her power to a man; a theme which allows for much of Shakespeare’s work and as long as Shakespeare continues to raise questions, and encourage debate, his work will always have relevance, particularly when we bring our modern approaches into focus with the texts. I’d like to end on a recommendation to visit the website Dr Emma Smith works with – The English and Media Centre. 6 Following the lecture, I contacted Dr Smith about how she viewed “The Taming of the Shrew”: I was wondering how you view The Taming of the Shrew, and how Katherina fits with your theory. Does she begin as a tragic figure and end as comic? I like the idea that she is in control at the end of the play – that her final speech could be ironic, a piece of revenge on the widow and her sister. Also, the change of location is full of trauma for her, but could be seen as ultimately redemptive. We recently saw the RSC’s production, which supported this view of the relationship between Katherina and Petruchio as a means of saving both characters, but many of the scenes focussing on their relationship lacked the humour I had expected. She replied: Thanks for being in touch: it's a really interesting question. I guess a vision of the play that is essentially recuperative - that sees K as incorporated into society through marriage rather than crushed - would work with the model of comic heroines in charge, to some extent, of their own plots. I too find that idea more palatable than the alternative - that Katherina is broken and defeated in the conclusion. But it's problematic, isn't it, that her longest speech - probably the longest in the whole play - is a speech of something like submission - so in dramatic terms she is dominant but the content of what she is saying is subservient. (I think Shrew has probably always been difficult, though, hence Shakespeare's own rewriting of it in Much Ado and Fletcher's later sequel 'The Woman's Prize, or the Tamer Tamed'). So I think Katherina does fit with the theory in that as a comic heroine she has a kind of dramatic agency and prominence. I just looked up the statistics for the number of lines (in the RSC complete Shakespeare ed Bate and Rasmussen): interesting figures. Petruchio has 22%, Tranio 11%, Kate 8%, Hortensio 8% - all four of these are in 8 scenes, so it seems that Kate is on stage not speaking quite a lot of the time. Thanks so much for bringing your students on Saturday. Can I alert you to the list of Shakespeare related websites I put together for the English and Media Centre website, in case it's of use? http://www.englishandmedia.co.uk/emag/index.html