Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism

Nineteenth- Century

Literature Criticism

Mf

Edgar Allan Poe

1809-1849

Author Index

Plumly, Stanley (Ross) 1939- CLC 33

See also CA 108; 110; DLB 5

Plumpe, Friedrich Wilhelm

1888-1931

See also C A 112

TCLC 53 if Poe, Edgar Allan

~" 1809-1849 .

NCLC 1,H6-DA; DAB;

PC IjSSC 1; WLC

See also AAYA 14; CDALB 1640-1865;

DLB 3, 59, 73, 74; SATA 23

Poet of Titchfield Street, The

See Pound, Ezra (Weston Loomis)

Pohl, Frederik 1919- ............. CLC 18

See also CA 61-64; CAAS 1; CANR 11, 37;

DLB 8; MTCW; SATA 24

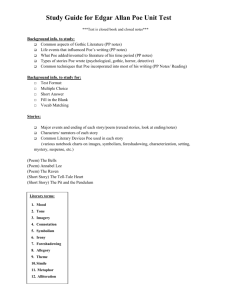

American short story writer, poet, critic, editor, novelist, and essayist.

The following entry presents criticism on Poe's short stories.

For additional information on Poe's career and his short stories,

see NCLC, Vol. 1.

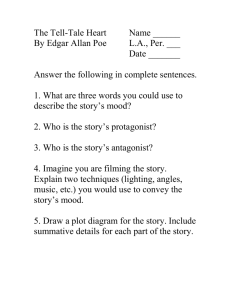

Poe's stature as a major figure in world literature is based in large part on his short stories and on his critical theories, which established a highly influential model for the short form in fiction. Regarded by literary historians as the architect of the modern short story, Poe is credited with the invention of several popular story genres: the modern horror tale, the science fiction tale, and the detective story. Both his short stories and his critical writings are also considered important for their profound impact on generations of later writers. Twentieth-century scholars have discerned in such well-known short stories by

Poe as "The Fall of the House of Usher," "The Black Cat," and "The Cask of Amontillado" a seminal contribution to the development of various modern literary themes, including the alienation of the self and the nature of the subconscious. Although during the nineteenth century critics failed to recognize the true nature of Poe's achievement, he is now acclaimed as one of literature's most original and influential practitioners of the short story form.

Poe's father and mother were professional actors who died before he was three years old, and he was raised in the home of John Allan, a prosperous exporter in Richmond, Virginia.

Poe attended the best schools in Richmond and began writing poetry as an adolescent. In 1826 he was sent to the University of Virginia. There Poe distinguished himself academically but, as a result of gambling debts and inadequate financial support from Allan, left after less than a year. His relationship with

Allan disintegrated further upon his return to Richmond in

1827, and soon afterward he left for Boston, where he enlisted in the army and published his first poetry collection, Tamer-

lane, and Other Poems. The book went unnoticed by readers and reviewers, and a second collection received only slightly more attention when it appeared in 1829. That same year Poe was honorably discharged from the army and, with Allan's consent, he entered West Point. However, because Allan would neither provide him with sufficient funds to maintain himself nor allow him to resign from the Academy, Poe deliberately gained a dismissal by ignoring his duties and violating regulations. He subsequently went to New York, where his Poems azines Poe would direct over the next ten years and through which he rose to prominence as one of the leading literary critics in America. Nonetheless, while Poe's writings began to gain attention in the late 1830s and 1840s, the profits from his journalism remained meager, and he was forced to move several times in pursuit of a better income, editing Burton's Gen-

tleman's Magazine and Graham's Magazine in Philadelphia and the Broadway Journal in New York. The money he received from the publication of his two collections of short stories, Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque and Tales by

Edgar A. Poe, as well as from his other works, was also minimal. After his wife's death in 1847, Poe was involved in a number of romances and became engaged to his boyhood

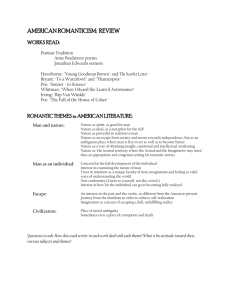

TITLE INDEX

"The Cascade of Melsingah" (Bryant) 6:180

"A Case That Was Dropped" (Leskov)

See "Pogassee delo"

"Casey's Tabble Dote" (Field) 3:209

"Casey's Table d'Hote" (Field) 3:205

"Cashel of Munster" (Ferguson) 33:294

"Casino des trepasses" (Corbiere) 43:32

"The Cask of Amontillado" (Poe) 1:500, 506;

16:303, 309(329)332

"Cassandra Southwick" (Whittier) 8:489,

505, 509-11, 513, 515, 527, 530

Cassiodor (Eminescu) 33:266

The Cassique of Accabee (Simms) 3:504

The Cassique of Kiawah (Simms) 3:503, 508,

514

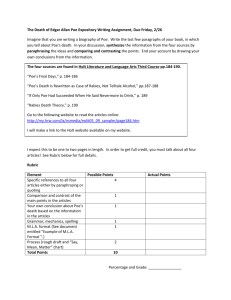

JAMES W. GARGANO (essay date 1963)

[Gargano contends that the often turgid and overwritten prose of

Poe's narrators is deliberately intended to reflect their disturbed states of mind and should not be confused with Poe's own prose style. For additional commentary by Gargano on Poe's short stories, see excerpt dated I960.}

Part of the widespread critical condescension toward Edgar

Allan Poe's short stories undoubtedly stems from impatience with what is taken to be his "cheap" or embarrassing Gothic style. Finding turgidity, hysteria, and crudely poetic overemphasis in Poe's works, many critics refuse to accept him as a really serious writer, (p. 177)

It goes without saying that Poe, like other creative men, is sometimes at the mercy of his own worst qualities. Yet the contention that he is fundamentally a bad or tawdry stylist appears to me to be rather facile and sophistical. It is based, ultimately, on the untenable and often unanalyzed assumption

•

9

* meaning of his existence resides in the tomb in which he has, symbolically, buried himself. In other words, Poe leaves little doubt that the narrator has violated his own mind and humanity, that the external act has had its destructive inner consequences.

The same artistic integrity and seriousness of purpose evident in "The Cask of Amontillado" can be discovered in "The

Black Cat." No matter what covert meanings one may find in this much-discussed story, it can hardly be denied that the nameless narrator does not speak for Poe. Whereas the narrator, at the beginning of his "confession," admits that he cannot explain the events which overwhelmed him, Poe's organization of his episodes provides an unmistakable clue to his protagonist's psychic deterioration. The tale has two distinct, almost parallel parts: in the first, the narrator's inner moral collapse is presented in largely symbolic narrative; in the second part, the consequences of his self-violation precipitate an act of murder, punishable by society. Each section of the story deals with an ominous cat, an atrocity, and an expose of a "crime." In the first section, the narrator's house is consumed by fire after he has mutilated and subsequently hanged Pluto, his pet cat.

Blindly, he refuses to grant any connection between his violence and the fire; yet the image of a hanged cat on the one remaining wall indicates that he will be haunted and hag-ridden by his deed. The sinister figure of Pluto, seen by a crowd of neighbors, is symbolically both an accusation and a portent, an enigma to the spectators but an infallible sign to the reader.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY LITERATURE CRITICISM,(Vol. 16)

blunts his powers of self-analysis; he is guided by his delusions to the climax of damnation. Clearly, Poe does n Jt espouse his protagonist's theory any more than he approves of the specious rationalizations of his other narrators. Just as the narrator's well constructed house has a fatal flaw, so the theory of perverseness is flawed because it really explains nothing. Moreover, even the most cursory reader must be struck by the fact that the narrator is most "possessed and maddened" when he most proudly boasts of his self-control. If the narrator obviously cannot be believed at the end of the tale, what argument is there for assuming that he must be telling the truth when he earlier tries to evade responsibility for his "sin" by slippery rationalizations?

A close analysis of "The Black Cat" must certainly exonerate

Poe of the charge of merely sensational writing. The final frenzy of the narrator, with its accumulation of superlatives, cannot be ridiculed as an example of Poe's style. The breakdown of the shrieking criminal does not reflect a similar breakdown in the author. Poe, I maintain, is a serious artist who explores the neuroses of his characters with probing intelligence. He permits his narrator to revel and flounder into torment, but he sees beyond the torment to its causes.

In conclusion, then, the five tales I have commented on display

Poe's deliberate craftsmanship and penetrating sense of irony.

If my thesis is correct, Poe's narrators should not be construed as his mouthpieces; instead they should be regarded as expressing, in "charged" language indicative of their internal disturbances, their own peculiarly nightmarish visions. Poe, I contend, is conscious of the abnormalities of his narrators and does not condone the intellectual ruses through which they strive, only too earnestly, to justify themselves. In short, though his narrators are often febrile or demented, Poe is conspicuously "sane." They may be "decidedly primitive" or "wildly incoherent," but Poe, in his stories at least, is mature and lucid, (pp. 177-81) j //James W. Gargano, "The Question of Poe's Nar-\\ in College English, Vol. 25, No. 3, Decem-)/

(\

KENNETH GRAHAM (essay date 1967)

[In the following excerpt from his introduction to a collection of

Poe's tales, Graham surveys several of their unifying characteristics, including their symbolism and emphasis on metaphysical concerns.]

Poe's narrations are all, like the one found in a bottle ["MS.

Found in a Bottle"], manuscripts sent back from the edge of nothingness. With unique single-mindedness and intensity they probe into a spirit world, at times dark, at times beautiful, that underlies and destroys all the material phenomena of life, a world of the whirlpool, of the pit and the grave, of consciousness-after-death, of mystically alluring eyes, of torture, of the desire to kill, of guilt, madness, and, in the end, utter silence.

They may be narrowly obsessive and joyless, but their continuing power is founded on one recognizable and even familiar vision of life: that an awareness of death is the starting-point of knowledge, and that reality is not solid and reasonable but a flux, a maelstrom like the Norwegian fisherman's that contains within it some destructive promise of eternity. Yet Poe is at the same time incorrigibly reasonable. Again like the fisherman lost in the maelstrom, his mind acts like a scientist's even as he perceives the inadequacy of science to attain Truth.

A part of his creating imagination always clings to the solid

Nineteenth- Century

Literature, Criticism

NINETEENTH-CENTURY LITERATURE CRITICISM,(V

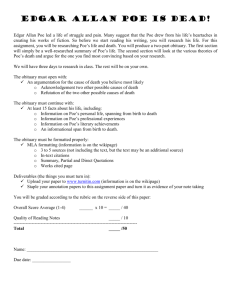

ADDITIONAL^IBLIOGRAPHY^

Abel, Darrel. "A Key to the House of Usher." University of Toronto

Quarterly XVIII, No. 2 (January 1949): 176-85.

Argues that "The Fall of the House of Usher" is a "consummate psychological allegory" that anticipates the methods of Franz

Kafka.

Aldiss, Brian W. "'A Clear-Sighted, Sickly Literature': Edgar Allan

Poe." In his Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction, pp. 40-56. New York: Schocken Books, 1974.

Discusses Poe's contribution to the science fiction genre.

Basler, Roy P. "The Interpretation of 'Ligeia'." College English 5,

No. 7 (April 1944): 363-72.

Suggests that "Ligeia" is primarily a study of madness and obsession rather than a horror story.

Beaver, Harold. Introduction to The Science Fiction of Edgar Allan

Poe, by Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Harold Beaver, pp. vii-xxi. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1976.

A general discussion of Poe's contribution to science fiction.

Bloom, Harold, ed. Edgar Allan Poe. Modern Critical Views. New

York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1985, 155 p.

A collection of highly regarded twentieth-century essays on Poe, including a number of influential studies of his tales.

Buranelli, Vincent. "Fiction Themes." In his Edgar Allan Poe, pp.

64-86. Twayne's United States Authors Series, edited by Sylvia E.

Bowman, no. 4. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1961.

A general introduction to Poe's short stories.

Carlson, Eric W., ed. The Recognition of Edgar Allan Poe: Selected

Criticism since 1829. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1966,

316 p.

Reprints important criticism on Poe's works by various nineteenthand twentieth-century commentators.

Dameron, J. Lasley, and Cauthen, Irby B., Jr. Edgar Allan Poe: A

Bibliography of Criticism, 1827-1967. A John Cook Wyllie Memorial

Publication. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974, 386 p.

An annotated guide to critical and biographical writings on Poe published prior to 1968.

Daniel, Robert. "Poe's Detective God." Furioso VI, No. 3 (Summer

1951): 45-54.

A study of Poe's fictional detective, C. Auguste Dupin.

Eddings, Dennis W. The Naiad Voice: Essays on Poe's Satiric Hoax-

ing. National University Publications. Port Washington, N.Y.: Associated Faculty Press, 1983, 175 p.

A collection of essays devoted to understanding the satirical intent of Poe's comic tales.

Feidelson, Charles, Jr. "Poe." In his Symbolism and American Lit-

erature, pp. 35-42. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953.

Explores Poe's use of symbols in his tales within the context of the tradition of symbolism in American literature.

Fletcher, Richard M. The Stylistic Development of Edgar Allan Poe.

De Pro Prietatibus Litterarum, Series Practica 55, edited by C. H. van

Schooneveld. The Hague: Mouton, 1973, 192 p.

Explores the evolution of Poe's style in both his poetry and fiction, focusing on such topics as his vocabulary, major themes, and use of symbols.

POE

Griffith, Clark. "Poe's 'Ligeia' and the English Romantics." Uni-

versity of Toronto Quarterly XXIV, No. 1 (October 1954): 8-25.

Maintains that "Ligeia" is primarily a satire of Gothic fiction.

Hoffman, Daniel. Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. 1972. Reprint. New

York: Random House, Vintage Books, 1985, 335 p.

A highly regarded study of Poe's works that offers a thematic approach to understanding various groups of his short stories.

Howarth, William L., ed. Twentieth Century Interpretations of Poe's

Tales: A Collection of Critical Essays. Twentieth Century Interpretations, edited by Maynard Mack. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-

Hall, Spectrum Books, 1971, 116 p.

Reprints selected twentieth-century criticism on Poe's tales.

Hyneman, Esther F. Edgar Allan Poe: An Annotated Bibliography of

Books and Articles in English, 1827-1973. Research Bibliographies in

American Literature, no. 2. Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1974, 375 p.

An annotated survey of writings about Poe and his works published between 1827 and 1973.

Kesterson, David B., ed. Critics on Poe. Readings in Literary Criticism, no. 22. Coral Gables, Fla.: University of Miami Press, 1973,

128 p.

A collection of seminal essays on Poe and his writings by various nineteenth- and twentieth-century critics.

Ketterer, David. The Rationale of Deception in Poe. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana State University Press, 1979, 285 p.

A study of "deception as theme and technique" in Poe's works.

Knapp, BettinaL. "The Tales." In her Edgar Allan Poe, pp. 101-204.

Literature and Life Series. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing

Co., 1984.

A four-part study of major thematic elements in Poe' s short stories, focusing on what Knapp describes as "The Descent," "The Anima," "The Shadow," and "The Mystical Quest."

Lauber, John. " 'Ligeia' and Its Critics: A Plea for Literalism. "Studies

in Short Fiction IV, No. 1 (Fall 1966): 28-32.

Argues in favor of a literal interpretation of the plot of "Ligeia."

Levine, Stuart. Edgar Poe: Seer and Craftsman. Deland, Fla.: Everett/

Edwards, 1972, 282 p.

Probes the mythic elements underlying Poe's horror tales, focusing on "The Cask of Amontillado."

Levine, Stuart, and Levine, Susan, eds. The Short Fiction of Edgar

Allan Poe: An Annotated Edition, by Edgar Allan Poe. Indianapolis:

Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1976, 633 p.

An annotated edition of the tales that includes pictures, maps, and diagrams, as well as explanatory notes for each story.

Liebman, Sheldon W. "Poe's Tales and His Theory of the Poetic

Experience." Studies in Short Fiction VII, No. 4 (Fall 1970): 582-96.

Investigates the relationship between Poe's short stories and his ideas concerning poetry.

Mooney, Stephen L. "Comic Intent in Poe's Tales: Five Criteria."

Modern Language Notes LXXVI, No. 5 (May 1961): 432-34.

Outlines five common indications of humorous purpose in Poe's short stories.

. "The Comic in Poe's Fiction." American Literature 33, No.

4 (January 1962): 433-41.

Examines the humorous and satirical aspects of Poe's comic tales.

Pollin, Burton R. Dictionary of Names and Titles in Poe's Collected

Works. New York: Da Capo Press, 1968, 212 p.