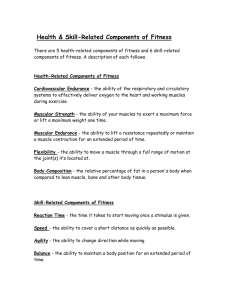

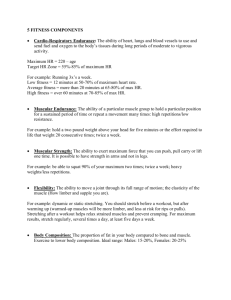

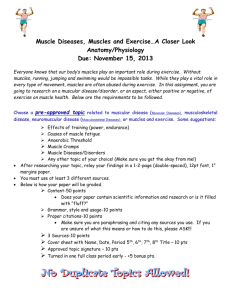

Muscular Strength and Endurance

advertisement