Part Two - Vet School Success

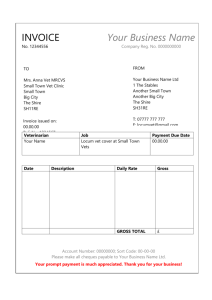

advertisement