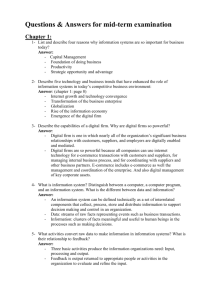

Management Information Systems

advertisement